How do you feel when you read the terms “wrath of God” and “penal substitution”? Do you feel that something of profound and eternal theological importance has been stated, even if you’re not quite sure what it is? If so, you are probably on the reactionary Reformed side of the theological fence that currently divides modern evangelicalism. Or do you squirm inwardly, wincing at language that sounds distinctly medieval and barbaric? If so, then undoubtedly you are of a more progressive persuasion.

I have argued before and, for the benefit of someone who recently asked me about wrath and the death of Jesus, I will argue again that whichever side of the fence we are on, the theological mindset of modern evangelicalism simply does not allow us to read the New Testament story for what it is. The problem is that neither the Reformed nor the progressive position understands history. In this connection, I recommend Scot McKnight’s multipart response to Samuel V. Adams’ critique of N.T. Wright’s historical method.

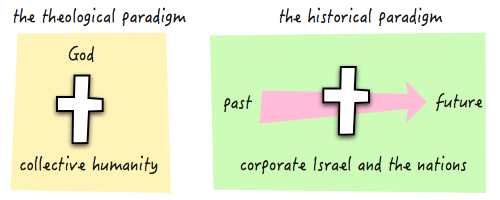

Evangelical theologies, whether Reformed or progressive, work with a vertical paradigm: the cross intervenes between God and humanity, and various theories of atonement are proposed to explain the nature of this intervention.

The New Testament, however, gives us a historical narrative, according to which the cross stands between the past and the future, between a story about what has happened to a people and a story about what will happen.

In the Old Testament wrath is the concrete manifestation of God’s anger against serious and persistent wrongdoing. It is directed either against Israel or against powerful nations in the region which threatened or opposed Israel, and very often the two are connected.

So, for example, God “comforts” ruined Jerusalem with the thought that the “cup of his wrath” against the city—a “cup of staggering”—will be taken from her and put into the hand of her tormentors (Is. 51:17-23; cf. Hab. 2:16). God has used the Babylonians to punish his people by the destruction of Jerusalem and exile, but the Babylonians will be punished in turn for their idolatry, injustice, and violence. Repentance may lead to a change of heart of God’s part and the avoidance of wrath, but this happens rarely.

To my narrative-historical way of thinking, the content of the New Testament—the stuff of Christian belief—is generated by exactly this narrative pattern. The boundary of New Testament “theology” can be defined as the ellipse (C) drawn by a loop of string around the two focal points of wrath against Israel (A) and wrath against the pagan nations (B). There is a bigger story about God, creation and humanity beyond this (D), but it is in the background, at the margins. It is important and it has a bearing on the development of New Testament thought, but it is not what the New Testament is about.

In simple terms, first, the whole story about Jesus (birth, ministry, teaching, calling of disciples, death and resurrection) happens because the wrath of God is again directed against Israel.

The Jews are on a broad and easy road leading to destruction within a generation. Jesus warns of a day when Jerusalem will be surrounded by armies: there will be great distress in the land and “wrath against this people” (Lk. 21:20, 23). But he makes available a narrow and painful road leading to life; and if his disciples had not been willing to take up their own crosses and follow him down this difficult road, there would have been no viable future for the people of God.

Then secondly, this story about Jesus and the wrath of God against Israel triggers (A→B) another story about the nations. The resurrection of Jesus and his ascension to the right hand of God is understood to mean that God has fixed a day when he will judge the pagan world (Acts 17:30-31). There will be wrath against the Jew, but also wrath against the Greek (cf. Rom. 2:6-11). The church in Thessalonica was made up of pagans who had abandoned the worship of idols and were waiting for Jesus to deliver them from the wrath to come (1 Thess. 1:19-10). This cannot be reduced to personal salvation: as in the Old Testament it is played out over historical time spans.

The proclamation of coming wrath is accompanied by a call to repentance as a way of escaping wrath. This is true both for Jews and for Gentiles. John the Baptist says to the Pharisees and Sadducees, “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruit in keeping with repentance” (Matt. 3:7–8). Paul tells the men of Athens that God now “commands all people everywhere to repent” from their idolatry and the unrighteous practices associated with it (Acts 17:30). In the end, the Gentiles were more inclined to repent of their idolatry, etc., than the Jews were to repent of their stiff-neckedness.

The death of Jesus and wrath against the Jew (A)

I would then suggest that the eschatological narrative of the New Testament works against the theological assumption that the death of Jesus has a unitary meaning.

In the first place, Jesus’ death must be interpreted in relation to the expectation of wrath against Israel (A). The crucifixion of Jesus outside the walls of Jerusalem was a quite striking anticipation of the “punishment” that the Jews would suffer at the hands of Rome. According to Josephus, thousands of captured Jews were crucified in sight of the walls during the course of the siege.

In this respect, it would be a mistake to say that the wrath of God was poured out on Jesus. It would be poured out on Jerusalem. But there is clearly a sense in which, in obedient pursuit of his Father’s purposes, Jesus “fell victim” to the eschatological crisis of the end of the age of second temple Judaism. He was, we might almost say, collateral damage.

The cup of suffering that he accepted in Gethsemane (Matt. 26:39), which his disciples would also have to drink (Matt. 20:23), was in an important sense the cup of God’s judgment against Israel (cf. Ezek. 23:31-34).

Jesus died because the unrighteous leaders of Israel refused to accept his claim to kingship—the right to determine Israel’s future—and handed him over to the Romans to be executed. Jesus died for the sake of a new future for the people of God, and his conviction was vindicated by his resurrection from the dead and exaltation to the right hand of the Father to reign as Israel’s king throughout the coming ages. He embodied in himself the pain and triumph of the eschatological transition.

But the idea was already current that the death of an innocent or righteous person might avert or limit wrath or bring it to an end. Isaiah had envisaged a servant of the Lord who suffers as a consequence of Israel’s sins and whose suffering brings peace and healing for the nation (Is. 53:4-6). The author of 4 Maccabees writes of the martyrs killed by the tyrant Antiochus that they were a “ransom (antipsuchon) for the sin of the nation”; through their blood and the “propitiatory (hilastēriou) of their death” Israel was saved from its afflictions—that is, from the wrath of God—and the “homeland was purified” (4 Macc. 17:21-22).

A straight line can be drawn from here, through Jesus’ death, to Paul’s argument in Romans 2-3. Paul’s critique is directed against Jews who think that they are above the Law, so to speak. Actually, the Jewish Law condemns Israel because the Jews are just as sinful as the Gentiles. Therefore, God is in the right to “inflict wrath on us” (Rom. 2:5). In fact, God cannot judge the world (B) without first judging his own people (A)—the Jew first, then the Greek (Rom. 3:6).

But if God allows his people to be destroyed by Rome, what has happened to the promise to Abraham that his descendants would inherit the world (Rom. 4:13)? The answer, of course, is Jesus; and Paul explains that the righteousness or rightness of God has been demonstrated “through the faithfulness of Jesus Christ”, whose death can be seen as a “propitiation”—an atonement or hilastērion—for the sins of Israel (Rom. 3:25; cf. Heb. 2:17). (If you want to explore this narrative-historical perspective on Romans further, see “How to rescue Romans from the fish tank of Reformed theology and return it to the sea of history” or my book The Future of the People of God: Reading Romans Before and After Christendom.)

In the context of the story about the wrath of God against Israel, therefore, the martyrdom of Jesus is interpreted appropriately in covenantal and eschatological terms. It was a “sacrifice” analogous to the passover lamb or the atonement ritual that made possible a new future for a captive or sinful people. He suffered from the violence that would ultimately destroy the nation. He experienced the wrath of God against his people. He died so that Israel might be purified and have new life in the age to come.

All this could in principle be couched in the language of “penal substitution”, provided we ditched all the existential-forensic baggage of Reformed theologies.

The death of Jesus and wrath against the Greek (B)

In the context of the story of God’s wrath against the pagan world, however, the covenantal language makes less sense. Jesus died because of the coming judgment on Israel. He did not die on account of—or in anticipation of—the wrath of God poured out on the idolatrous nations and the supreme opponent, Rome. On the contrary, wrath came on the Greek-Roman world because Jesus had suffered and had been raised from the dead (Acts 17:30-31).

But this does not mean that the cross was irrelevant for the Gentiles. His death for the sins of his people (cf. Matt. 1:21) opened the door subsequently for the inclusion of Gentiles on equal terms.

Because Jesus’ obedience or faithfulness solved the problem of “wrath against the Jew” apart from the Law, it became possible for Gentiles to be incorporated into the renewed people of God. Both Jews and Gentiles were saved from the coming wrath not by performing works of the Jewish Law but by believing the story of Philippians 2:6-11: that Jesus’ had been obedient to the point of death on a cross, that he had been exalted to the right hand of the Father, and that he had been given authority to judge and rule over the nations. So Paul writes in Ephesians 2:11-22 that his Gentile readers are now members of the household of God because through his death Jesus made the Jewish Law irrelevant.

This is not the whole picture. There are other ways in which the New Testament speaks about the significance of Jesus’ death for the Gentiles. For example, Paul tells the predominantly Gentile church in Colossae that God has cancelled the record of debt against them by nailing it to the cross—an image of forgiveness. The cross, moreover, is the means by which the “rulers and authorities” that governed the ancient world were humiliated and disarmed—supreme authority now lies with the risen Christ (Col. 2:13-15).

We also need to take note of the fact that John already tends to collapse the narrative ellipse into a theological circle: Jesus is the lamb of God who “takes away the sin of the world” (Jn. 1:29); he is the “propitiation (hilasmos) for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of the whole world” (1 Jn. 2:2).

Nevertheless, I think the basic argument holds. Jesus died because of God’s wrath against Israel, and his death is interpreted in terms appropriate to that narrative. That death for Israel, as a solution apart from the Law, had the further effect of opening the door of membership in the covenant community to Gentiles. But in this context the language associated with Jewish martyrdom—the language of wrath, punishment, substitution, atonement—does not have the same direct narrative relevance.

If we ask, finally, how we are to speak of Jesus’ death today, I suggest that we simply need to tell the whole story—and, of course, believe it. By that we will, in the end, be justified.

A while back, when talking about the relationship of Jesus’ death to the wrath of God, I also used the analogy of collateral damage.

Although this is pure speculation, I wondered aloud if this didn’t play into God’s historical response. A sort of moment of, “Oh crap. My Son died because of all this. Maybe I’d better make sure this doesn’t get out of hand.”

I mean, if the theology is that that the death of faithful martyr could avert or forestall God’s wrath against the party the martyr came from, there has to be some reason that works. Once again, it’s all speculation, but I wonder what goes on in God’s mind when a faithful martyr dies under the mechanism of His wrath.

The texts strongly suggest, surely, that it is the logic of sacrifice that must explain how martyrdom came to be understood as redemptive for Israel: “Yet it was the will of the LORD to crush him; he has put him to grief; when his soul makes an offering for guilt, he shall see his offspring; he shall prolong his days…” (Is. 53:10).

Historically, though, it was the need to withstand Antiochus’ attempts to wipe out Jewish faith and practice in Jerusalem that gave rise to the belief that the suffering of a righteous individual would save Israel from destruction—and would be rewarded by personal resurrection.

Prior to that the threat to Jewish faith had been at the national-political level, notably the Babylonian invasion and exile.

@Andrew Perriman:

Agreed. I guess my question is really: what is the logic of sacrifice?

What did the Jews do wrong other than reject Jesus’ kingship?

And why would they be punished for rejecting something that they had no reason to expect? Wouldn’t that be like God punishing Christians for rejecting Islam?

The Hebrews had a long-standing religion based on promises from God that were outlined in their own scripture, none of which had anything to do YHWH impregnating a virgin, coming to earth as part of a Trinity, or dying for sins.

When he was alive, it is not clear whether Jesus even claimed any of these things for himself. So when Jesus’ followers made up the theology of substitution (or however you frame it) how could the Jews have been expected to buy it? It seems to me God should have been happy with the fervency of their desire to do what they thought was the right thing and rejecting the ideas of an interloper.

What else did the Jews get punished for? And why would it have been fair to be punished so harshly for following their own religion?

@Paul:

The parable of the wicked tenants points to the fact that the Jews did not just reject Jesus’ kingship. The owner sends servants over a period of time to get the fruit of righteousness but to no avail. In the end he sends his Son who is also killed by the tenants. It is the persistent rebelliousness of the tenants and their refusal to produce the fruit that accounts for their destruction, not merely the climactic rejection of the Son.

It is also important to note that the justification for this judgment is in the Law. If Israel did not walk in YHWH’s ways—did not produce the fruit of righteousness—then eventually the nation would face the “curses” described, for example, in Deuteronomy 28:15-68, culminating in invasion, devastation and dispersion. There is nothing arbitrary about Jesus’ announcement of wrath against Israel.

In that sense, yes, the Jews were punished for “following their own religion”, because the punishment was part-and-parcel of their religion.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew, yes, that is the Christian spin on the Jewish problem. Christians had to claim that God turned his back on the Jews and that they were the chosen ones.

But it doesn’t answer what the Jews were doing that was so evil in God’s eyes at the time. How did they not walk in god’s ways? What was the bad fruit? History records that the Jews were very fervent in their monotheism. So other than rejecting the claims of Paul, why were they punished?

@Paul:

The Old Testament is full of prophetic indictments against Israel. Their tenure under the Roman Empire was one of exile. That’s why Zechariah was “longing for the restoration of Israel” according to Luke’s birth narrative.

Of course, all we have to know about Israel “on the ground” at the time is from these writings that for the most part came much later than the events they describe, but midrashim and Jewish apocalyptic literature seems to bear out this self-consciousness.

Hey, you are posting Thursday, where I am it’s still Wednesday. You should tell me who wins tomorrow’s sporting events.

My point is that the idea that people were evil was projected backwards to explain something that happened, and it would not have been apparent at the time. Jews didn’t do anything wrong, but since they were cast out of Jerusalem, an explanation was invented that they displeased God.

@Paul:

That’s a possible hypothesis, but you’d have to assert that idea over against what historical evidence we’ve got. The idea that Israel was suffering for breaking the covenant goes back several centuries before Christ — almost a thousand years.

Historical information is what I want. What exactly did the Jews do break the covenant in Jesus time? The only reason we think that is because they lost the fight with the Romans and Christianity became more popular. What is the contemporaneous evidence that they were displeasing god?

@Paul:

Why does John the Baptist appear on the scene calling for repentance and baptism to escape the prophesied judgement? Why does Jesus have such harsh words for the Pharisees, chief priests, and scribes, but such kind words for fisherman, tax collectors, and the poor?

Well, most scholars would say that the words of Jesus in that regard reflected the views of later Christians and were not things he actually said. John was a prophet who preached the imminent coming of the Kingdom of God, which encompassed Jews taking over world rulership from the Romans. So it embodied criticism of Jews, but it was a lot different than saying that the Jews were cursed.

But the idea was already current that the death of an innocent or righteous person might avert or limit wrath or bring it to an end. Isaiah had envisaged a servant of the Lord who suffers as a consequence of Israel’s sins and whose suffering brings peace and healing for the nation (Is. 53:4-6). The author of 4 Maccabees writes of the martyrs killed by the tyrant Antiochus that they were a “ransom (antipsuchon) for the sin of the nation”; through their blood and the “propitiatory (hilastēriou) of their death” Israel was saved from its afflictions—that is, from the wrath of God—and the “homeland was purified” (4 Macc. 17:21-22).

Which I guess is also reflected here…

Jn 11:49-52 And one of them, Caiaphas, being high priest that year, said to them, “You know nothing at all, nor do you consider that it is expedient for us that one man should die for the people, and not that the whole nation should perish.” Now this he did not say on his own authority; but being high priest that year he prophesied that Jesus would die for the nation, and not for that nation only, but also that He would gather together in one the children of God who were scattered abroad.

@davo:

Possibly, but Caiaphas’ argument is very pragmatic (“it is expedient”), the sacrificial language is missing, and presumably Caiaphas didn’t think that Jesus was innocent. But it does give us a very “realistic” political account of the saving effect of Jesus’ death.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

but Caiaphas’ argument is very pragmatic (“it is expedient”), the sacrificial language is missing

I’m not sure that is correct. Seems to me that Caiaphas is including a sacrifical element, only in his mind it’s to appease Rome not God. John then followed up stating that Caiaphas was speaking not on his own authority — meaning that he was prophesying (God speaking through him even though he didn’t know it) — and that Jesus would “die for the nation, and not for that nation only”. John’s interpretation of what Caiaphas said seems to also include a sacrificial element to it only John is applying it as an appeasement to God.

@Rich:

Caiaphas’ argument is not that Rome will be appeased. Rome was not asking for Jesus to be crucified—quite the contrary, Pilate washed his hands! The risk was that everyone would believe in Jesus and then “the Romans will come and take away both our place and our nation” (Jn. 11:48).

I’m not sure that John’s comment about Caiaphas speaking prophetically adds a sacrificial note. John could have said “die for the sin of the nation”. It seems to me that we read that too easily into the text.

@Rich:

Andrew,

after thinking about it a bit more, I do agree with you that from Caiaphas’ point of view it was not sacrifical. He was merely wanting to knock off Jesus to shut him up thus keeping Rome from destroying the nation. I do think John’s interpretation included a sacrifical element to it though.

The term “collateral damage” suggests to me an unnitentional consequence. But The NT presents Jesus’ death as the plan “before the foundations of the world”. Either way the squirming progressive type is still left with a God who’s intention was to have his people starved, tortured, crucified and slaughtered as punishment. It is the idea that this is what God is like that makes me squirm. And I would imagine “telling the whole story” like that would make most people uneasy about that presentation of God.

@Nicky:

The “collateral damage” metaphor was suggested very tentatively as a way of associating Jesus’ death with subsequent historical events.

The moral problem, however, is a real one, and I take your point. The Jews interpreted such disasters as the Babylonian invasion or the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple by Rome not as mere facts of history but as acts of YHWH. The interpretation was not arbitrary: it was a provision of the covenant and integral to the narrative.

Jesus put an end to the Law as things turned out, but I think that we have to view the appalling events of AD 66-70 as the final outworking of the covenant, so Jesus himself is implicated. The Jesus we meet in the Gospels himself warned his people that they faced a final, horrifying judgment of Gehenna because of their sins.

Judgment on Rome was also an outworking of the Old Testament narrative, but it is not envisaged in the same militaristic terms. Rome is brought down not by the sword but by the word of God and the faithful witness of the suffering churches.

I think we have to be honest about this and accept that it is part of the story that we tell. We are no longer under the old covenant, the rules have changed; but I don’t think we can make sense of Jesus without it. If we are going to use the Bible to explain ourselves, we have to take it for what it is, not redact it or allegorise to suit our modern sensibilities.

@Nicky:

Nicky,

with a God who’s intention was to have his people starved, tortured, crucified and slaughtered as punishment.

Don’t think I would say it was his intention.

To be fair God set established this punishment for their unfaithfulness and lack of willingness to repent. He provided a way out; the narrow road. I see it no different than me telling my daughters that if they continue down a certain road it will end in some form of punishment. It doesn’t make me a bad or unloving father for bringing about the punishment if they don’t turn from whatever course they were traveling. Not sure why that would make anyone squirm, but maybe I don’t get it because I’m not a progressive type; although I don’t see myself as being anywhere near the Reformed type either.

- Rich

@Rich:

Rich: What if you warned your daughters that if they keep sneaking out late at night to walk the streets they will eventually get raped and murdered (sorry but just trying to work with you e.g and the horror of ad 70) but then you arranged for that very thing to happen to them as punishment for their persistent disobedience?? I think that is a closer analogy to the Biblical story. Andrew I agree with everything you say in your response above. But what then do we do with our “modern sensibilities”? Deny them in order to embrace a God who arranges such horrors for his people and for his people’s enemies? Also Andrew, how have the rules changed and does this help at all in reconciling our modern sensibilities with the way we see God in the Bible? Seems to me if we want to see Christianity survive the current crises we have do this. As a Christian for 30 years and pastor for 13 I don’t know how to reconcile the picture of God in scripture with my modern sense that women and children shouldn’t be brutally tortured and murdered to satisfy the anger of an angry deity. How can I ask an unbeliever to embrace this story?.

@Nicky:

And to bring back to the beginning of your post Andrew — I don’t see how the vertical theologies of the reformed or progressive camps or the horizontal narrative approach really solve this basic problem. If Jesus came to show us that we have God wrong and we should love our enemies as God does and then died, though innocent, to demonstrate this way of doing power, and God put his stamp of approval on this way by resurrecting him. So we should follow in this new way of doing power, then that is a compelling and beautiful story. But i think Andrew and the reformed school is right in saying this is simply not how the Biblical writers saw it.

@Nicky:

I think it’s worth imagining a scenario where Israel (or analogous daughters) provoke the disastrous outcome/punishment. Going out late at night doesn’t provoke rape and murder but maybe going out late and robbing someone who is bigger and prone to violence could provoke murder. I’m thinking Jewish revolts. And possibly imagining how humans would dole out God’s justice/judgment/punishment imperfectly just as we assume the Church and the Bible represent human’s best effort at demonstrating God’s will but do so in a limited way. Could Rome, Babylon, etc also be subject to the same human limits at enacting God’s judgment on Israel through their peculiar brand of violence?

@Edwin:

Isn’t that sort of Habakkuk’s point? First, he complains that there is injustice in Israel, and YHWH does nothing about it. YHWH says, “Look among the nations…,” etc., because he is about to raise up the Chaldeans, who will be the means by which unrighteousness is punished in Israel. But then Habakkuk points out that the Babylonians are extremely wicked and violent and indiscriminate in their destruction—so what will happen to the righteous in Israel, who do not deserve to be collateral damage?

The answer is, on the one hand, that the righteous will live by their faith (Hab. 2:4), and on the other, that the Chaldeans themselves will in turn be judged: “Because you have plundered many nations, all the remnant of the peoples shall plunder you, for the blood of man and violence to the earth, to cities and all who dwell in them” (Hab. 2:8). There are other places where the foreign power is rebuked for exceeding its mandate.

I’m not sure we can say that the Chaldeans were doing their best to demonstrate the will of God, but certainly Habakkuk saw in the mess and bloodiness of these current affairs the hand of the God who judges and punishes. And I think that we have to say—notice Paul’s use of Habakkuk 2:4 in Romans 1:17—that just this paradigm applies in the New Testament. Israel is judged by means of Rome, the righteous live by their faith in the God who is managing this tumultuous process, and Rome eventually is judged by the rider on a white horse called “Faithful and True” (Rev. 19:11-16).

Recent comments