I will be at the Society of Biblical Literature International Meeting in London next week. First time to go to one of these things. I will be presenting a paper in the Paul and Pauline Literature section on Monday afternoon on “Sibylline Oracles and the Judgment of the Greeks”, but the other contributions look like they will be much more interesting and probably much more scholarly. If you’re going to be there, please look out for me.

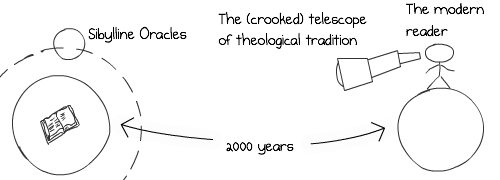

What I am trying to get at in the paper, at the hermeneutical level, is the change of understanding, the shift in perception, the opening of eyes, that happens when we read Romans from the remote and unfamiliar vantage point that a text such as Sibylline Oracles provides. I’m not suggesting that there is any direct influence, one way or the other, between the two texts, though if the Jewish stratum of Sibylline Oracles 1-2 was written in Galatia between 30 BC and AD 70 as J.J. Collins argues, there is every reason to think that Paul was well acquainted with the thought-world that gave birth to it.1 But with all due respect to the Reformers and their convictions regarding the perspicuity of scripture, the modern reader is handicapped by his lack of familiarity with the literary-historical context from which the New Testament emerged. It’s only when you get closer to this world that you realize how much of a distorting effect our theological telescopes can have.

The central section of Sibylline Oracles 1-2 envisages a divine judgment that will “break the glory of idols and shake the people of seven-hilled Rome” (2.15-19). The event will be accompanied by great turmoil: wealth will be destroyed, men will kill each other; there will be “famines and pestilence and thunderbolts on men who adjudicate without justice. But the “great God” will be a “saviour of pious men in all respects”. Peace will be re-established; the earth will become fruitful again, no longer partitioned by and in servitude to Rome; and “every port will be free for men as it was before” (2.20-33).

This is followed by a contest in which all people, from across the Greek-Roman oikoumenē, will strive to enter into the heavenly city. The criteria for success in this contest are given in a collection of moral and religious sayings from Pseudo-Phocylides. Pseudo-who? It doesn’t matter. The point is that this is a judgment of the nations, following the overthrow of pagan Rome, according to their works. The account is overlaid with a later Christian stratum (probably AD 70-150) which adds to this eschatological scenario in some important ways but doesn’t fundamentally change the Jewish eschatological premise.

My suggestion, then, will be that if—in our imaginations—we read Paul from the moon of the Sibylline Oracles as it orbits the world of the New Testament, rather than from our very different and very distant modern planet, we may find that we understand him much better.

The first part of Paul’s argument in the Letter (Rom. 1:18-3:20) has nothing to do with faith or atonement or salvation or the church or going to heaven when we die. Instead Paul takes great pains to lay out a very Jewish and very realistic claim—that there will be a day when “according to my gospel, God judges the secrets of men by Christ Jesus” (2:16). It will be a day of wrath, a day of “tribulation and distress” (2:5-10), when not only the Greeks but also the Jews will be judged according to what they have done. For those who “obey unrighteousness” there will be “wrath and fury”. But those who “by patience in well-doing seek for glory and honour and immortality” will be rewarded with “glory and honour and peace”, and everlasting life.

From our modern planet this may sound like a final judgment, but from the small satellite of the Sibylline Oracles, orbiting within the gravitational field of a remote planet, it sounds very much like a temporal judgment on the Greek-Roman world. The novel element that Paul inserts is the very contentious argument that the Jews have got themselves tragically implicated in this coming wrath.

This, I think, is where the argument of Romans begins: Paul addresses a number of issues relating to the fate of the Jews and the emergence of a community of faithfulness in the light of his conviction that in the foreseeable future God would overturn the world of Greece and Rome, putting an end to the whole impious system of pagan belief and practice and giving this world as an inheritance to the family of Abraham (cf. Rom. 4:13).

What we have failed to detect from our distant modern world is the realistic historical texture of Paul’s vision for a transformed oikoumenē. Texts such Sibylline Oracles help us to read from much closer up.

- 1J.H. Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, vol. 1, 331-32.

Andrew - I'll be slumming it in the slum district of Nairobi next week - about as far from the Sibylline Oracles as you can get. Otherwise I would have come as one of your cheer-leaders, and maybe asked a few planted questions (provided by you beforehand). I hope it goes well.

Wish we could be there. I just started your treatment on Romans and am enjoying it immensely!

@Eric:

Hello Eric! Next time you are passing through, give a call. We could arrange another flashmob conference in the Royal Festival Hall cafeteria. The subject: the Sybilline Oracles: Sybil our Contemporary? The speaker? Andrew - sorry to be using your site like Facebook. (Now there's an idea).

@peter wilkinson:

Peter, have often thought about it and certainly will! I really appreciate knowing you guys.

@peter wilkinson:

Peter, I'd like to 'friend' you on FB: how do I narrow my search?

@Eric:

Ask Andrew - he's my internet guru.

Recent comments