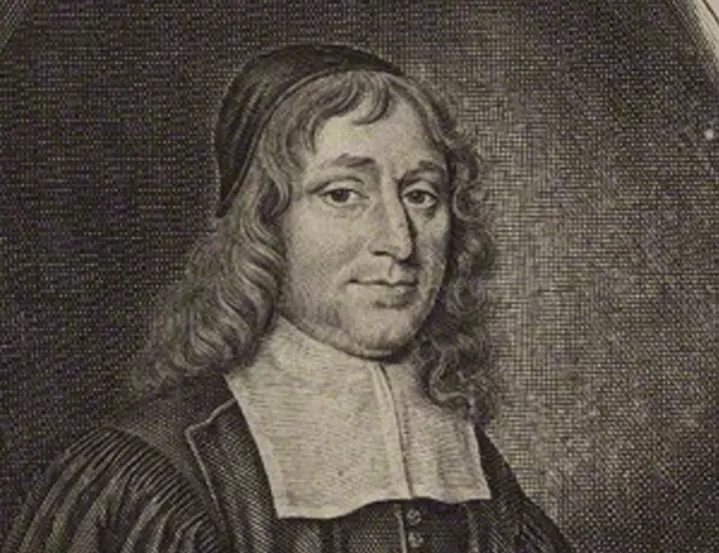

Matthew Poole was a seventeenth century English Presbyterian minister. Towards the end of his life he started work on a commentary on the Bible called Annotations upon the Holy Bible. Wherein The Sacred Text is Inserted, and various Readings Annex’d, together with the Parallel Scriptures, the more difficult Terms in each Verse are Explained, seeming Contradictions Reconciled, Questions and Doubts Resolved, and the whole Text opened. They don’t write titles like that any more, sadly.

Poole got as far as Isaiah 58 and then died, but the work was completed by friends and colleagues largely on the basis of Poole’s earlier Synopsis criticorum aliorumque Sacrae Scripturae interpretum. The section on Romans in Annotations was written by Richard Mayo.

Here I want to consider Mayo’s brief commentary on Romans 1:16-17 (Annotations Upon the Holy Bible, vol. 3, 480-481), a paragraph of some importance for understanding the letter as a whole:

For I am not ashamed of the gospel; for it is the power of God for salvation to all who believe, to the Jew first and to the Greek. For the righteousness of God in it is unveiled from faith for faith, as it is written, “The one righteous through faith shall live.” (Rom. 1:16-17*)

The letter, Mayo says, is partly doctrinal, partly practical (477-78). In the doctrinal part “we are taught the way and manner of our justification before God, that we are justified by faith, without the deeds of the law, by a righteousness which is imputed to us and not by any righteousness inherent in us.” This is proved in chapters one to four and amplified in five to eleven, and in this respect the letter is “the proper seat of that doctrine.”

This is an obviously Reformed reading of Romans, but Stephen Westerholm’s review of commentaries on Romans in his book Romans: Text, Readers, and the History of Interpretation suggests that it is only a highly focused instance of a hermeneutic that operated from Origen to Barth—and which, of course, determines most popular readings of the letter today. This is Paul answering the universal human questions of why we need to be saved, how we are saved, and how we should live once saved.

In the comment on Romans 1:16-17, Mayo notes that Paul is not ashamed to write to sophisticated Romans at the heart of the empire about the simple and foolish gospel of Christ. The gospel is the “power of God… for the conversion and salvation of the souls of men”—that is, “not the essential power of God, but the organical power.” The gospel is offered to all but profits only those who believe. It was declared first to the Jews, then to the “Gentiles, who he here calls Greeks.

The “righteousness of God” has been understood by some as meaning the “whole doctrine of salvation and eternal life,” and by others as the righteousness by which a person is justified. It is not “taught by reason or philosophy” but has been revealed in the gospel. “The beginning, the continuance, the accomplishment of our justification is wholly absolved by faith.”

Mayo suggests that the quotation from Habakkuk is better read “The just by faith shall live,” which better supports the central proposition that people are justified by faith. But he also acknowledges that there is

some difficulty to understand the fitness of this testimony to prove the conclusion in hand; for it is evident, that the prophet Habakkuk, in whom these words are found, doth speak of a temporal preservation; and what is that to eternal life?”

So here’s the conundrum—one which is commonly overlooked, so Mayo deserves credit for at least noticing the problem. Why does Paul use a passage that speaks of the preservation of Israel at the time of the Babylonian invasion to account for the spiritual preservation of individuals for eternal life? Here is Mayo’s answer:

The Babylonian captivity figured out our spiritual bondage under sin and Satan; and deliverance from that calamity did shadow forth our deliverance from hell, to be procured by Christ: compare Isa 40:2-4, with Mt 3:3. Again, general sentences applied to particular cases, are not thereby restrained to those particulars, but still retain the generality of their nature: see Mt 19:6. Again, one and the same faith apprehends and gives us interest in all the promises of God; and as by it we live in temporal dangers, so by it we are freed from eternal destruction.

So there is a general soteriological principle to be observed: God saves from eternal destruction or hell. The general principle may be evidenced in particular historical acts of divine salvation, such as the preservation of exiled Israel, but it cannot be restricted to any particular event. Also, the particular event can be said to prefigure or “figure out” the general spiritual principle. Deliverance from captivity in Babylon foreshadows deliverance from sin and Satan, just as the voice in the wilderness announcing the return of the exiles foreshadowed John the Baptist’s announcement of the coming of the Lord to deliver people from their sins.

Mayo also gives the example of Matthew 19:5-6: the general principle is that people should not separate what God has joined together in marriage, which has its origins in the particular instance of Adam and Eve. But any marriage is a temporal arrangement. Jesus does not refer to Adam and Eve becoming one flesh as a particular event that prefigures a spiritual union, in the way that Paul will do quite explicitly in Ephesians 5:31-32:

Therefore a man shall leave his father and mother and hold fast to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh.” This mystery is profound, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church. (Eph. 5:31-32)

So, in the absence of this sort of interpretive comment, on what grounds do we jump from the particular circumstances of the Babylonian invasion to a general doctrine of spiritual salvation—rather than to another instance of temporal deliverance?

My contention would be that Paul invokes Habakkuk’s narrative precisely because he believed that his people were facing a crisis of similar kind and proportions—perhaps a more serious crisis, but still “political” rather that spiritual, temporal rather than eternal.

The “gospel,” therefore, is a political message about an impending régime change that would impact both the Jew and the Greek, through which the righteousness or “rightness” of the God of Israel would be demonstrated to the ancient world.

Régime change would come with violence and disorder—the wrath of God against the Jew first, then the Greek, against the historic people of God and against the idolatrous and degenerate civilisation that so resolutely opposed the Lord and his anointed. Through this tumultuous transition, the “righteous” would live by their faith in the unfolding process that had been revealed to them.

The age-old preoccupation with the metaphysics of justification by faith misses the point—at least, it was of no interest to Paul. What he had in mind was a temporal outcome—ultimately, the conversion of the Greek-Roman world to worship of the God of Israel and the confession of allegiance to his Son—by which those who had believed all along that this would happen were quite naturally vindicated. The apostles and the churches would be found to have been in the right and not to have suffered so much in vain.

There is nothing remarkable about this sort of faith—speaking and acting in accordance with a foreseen future. We do it all the time. I’m doing it now, sitting on a train to Glasgow, expecting to attend the first Upper Room Church service after the sudden and untimely death of my dear friend Wes White. What is remarkable is that the future foreseen by Paul and his colleagues, the conversion of the Greek-Roman world, etc.—actually came to pass.

Recent comments