The title of the previous piece (“The death of Jesus: not as difficult to understand as you might think”) was perhaps a mistake. I suspect that many people found my narrative-historical reinterpretation as baffling as the classical theories of the atonement, if not more so.

In my defence I would say that the difficulty lies not in the narrative-historical account itself but in the amount of unthinking that we need to do—the mental effort involved in discounting a mountain of redundant conceptuality in order to see the narrative for what it was.

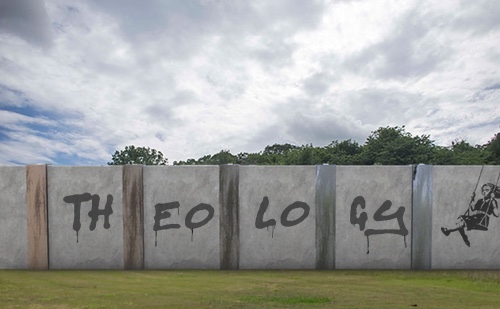

It’s a case of not being able to see the wood for the wall that has been built in front of it.

With that in mind, I thought I’d have a go at simplifying things, but alas it’s turned out instead as a draft pragmatic non-theory of the atonement.

- Jesus’ death as such didn’t achieve anything other than what was apparent in the course of history. Dying is just dying; it doesn’t do anything; it doesn’t move a lever somewhere in an unseen dimension of reality. What you see is what you get.

- A death can have profound historical implications: the death of Julius Caesar was a significant factor in the collapse of the Roman Republic; the death of Stephen led to the scattering of the church in Jerusalem (Acts 8:1); the death of Archduke Ferdinand kicked off the First World War. These are all momentous events triggered by an individual’s death, but they do not require a transcendent mechanism to account for the cause-and-effect.

- I take it that sacrifice in the Old Testament had no direct supernatural, mystical or metaphysical effect on the relationship between YHWH and Israel. It derived symbolic meaning from the part it played in the whole narrative of the covenant relationship between God and his people. The relationship was maintained by obedience on the part of the people and faithfulness on the part of God.

- In any case, the sacrifice of a human person is clearly not acceptable or explicable under the Jewish Law.

- The New Testament does not claim that God died on the cross—as though the death of God might achieve something that an ordinary human death could not achieve. That is, frankly, a nonsensical idea in biblical terms.

- Jesus is presented as fully obedient to the Father—fulfilling the covenant relationship—and innocent of the crime for which he is executed, but this is not made the ground for propositions regarding the transcendent effectiveness of his death.

- Jesus’ death gets its meaning from the part it plays in the story of Israel, but it has now become an apocalyptic narrative under the heading “kingdom of God”. What’s at stake is not the routine daily or even annual maintenance of the covenant but the future of a people threatened with annihilation by an all-powerful pagan empire.

- Theological accounts of the “cross” that fail to reckon with the Jewish-apocalyptic narrative are more of a nuisance than they’re worth.

- Jesus was not the first nor would he be the last “righteous” Jew to suffer at the hands of a corrupt régime in Jerusalem in collusion with a Gentile occupying force.

- Two things set Jesus’ death apart: vocation and vindication. First, Jesus was marked out as the Son or Servant who would fulfil YHWH’s purposes at this critical time—notably at his baptism. Secondly, God vindicated the faithfulness of his Son or Servant by raising him from the dead and seating him at his right hand.

- It is this dramatic act of divine vindication that fundamentally and irrevocably changes the course of history.

- There is a preamble to this story in the New Testament, which is that “the Word became flesh” and lived among the Jews; and conversely, that by him, as the image and firstborn Son of the creator God, “all things were created” (Jn. 1:14; Col. 1:15). But this does not interfere with the apocalyptic narrative of suffering and vindication.

- Jesus’ faithfulness and suffering in pursuit of the kingdom were paradigmatic for the faithfulness and suffering that would be required of the people of God if they were ultimately to triumph over the all-powerful pagan empire. He was, therefore, the “firstborn among many brothers”, the “firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep”, the “firstborn from the dead”, (Rom. 8:29; 1 Cor. 15:20; Col. 1:18). The writer to the Hebrews says: “let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God” (Heb. 12:1–2). Jesus was the first of many “brothers” to tread the path of suffering and became the great high priest who goes into the presence of God to intercede on behalf of his followers.

- How did people become part of the eschatological community? By believing that Jesus had died for the sins of his people and had been raised from the dead and seated at the right hand of God. People who believed that testimony were in the right before God, they were counted as righteous, they were justified—and more importantly, they would be justified or publicly vindicated when eventually Jesus was confessed by the nations. This is what the New Testament means by “justification by faith”.

- Because he died on account of the sins of Israel (especially the blindness and self-interest of the ruling class in Jerusalem), and because a new future became possible as a consequence of his death, it made excellent sense for his Jewish followers to speak of his death in sacrificial terms. We will see shortly that there were strong precedents for doing so.

- In effect, Old Testament stories are retold in order to give meaning to the new developments. Jesus was, as it were, the atonement victim, the Passover lamb, the suffering servant who “bore the sin of many”. What this language referred to was simply the historical event of Jesus’ death as part of the story of first century Israel, not some unseen metaphysical reality beyond the historical event.

- A different way needed to be found to speak about the significance of Jesus’ death for Gentiles who believed and received the Holy Spirit. The argument in Ephesians, for example, is simply that Jesus’ death led to the abolition of the Law, which until then had excluded Gentiles as Gentiles from the people of God (Eph. 2:11-22).

- What about believers today? Well, if we are going to be consistent, I think we have to say that: i) Jesus died for the sins of his people as part of the narrative of first century Judaism; ii) his death had the secondary effect of removing the barrier of the Law with the result that Gentiles could participate by believing that God had raised his Son from the dead, etc., without keeping the Jewish Law; iii) people today who believe this story and confess Jesus as Lord are brought into relationship with the creator God in the context of his historical covenant people.

Traditionally, we have read the New Testament texts as though they more or less knowingly foreshadowed later theoretical accounts of the atonement. A better hermeneutical method. I suggest, would be to read the stories of and arguments about Jesus’ death in the light of contemporary Jewish accounts of martyrdom. That is what is involved in reading historically rather than theologically.

The martyrs under Antiochus

The author of 4 Maccabees (plausibly dated AD 20-50) has this to say about the martyrs under Antiochus:

And these who have been divinely sanctified are honored not only with this honor, but also in that, thanks to them, our enemies did not prevail over our nation; the tyrant was punished, and the homeland was purified, since they became, as it were, a ransom for the sin of the nation. And through the blood of those pious people and the propitiatory of their death, divine Providence preserved Israel, though before it had been afflicted. (4 Macc. 17:20–22)

Their deaths were regarded as 1) a “ransom” (antipsuchon) and “propitiatory” (hilastērion) for the sin of the nation. Earlier the old man Eleazar, at the point of death, prayed: “Be merciful to your people, and be satisfied with our punishment on their behalf. Make my blood their purification, and take my life in exchange (antipsuchon) for theirs” (4 Macc. 6:28–29).

![Gustave Doré, The Martyrdom of Eleazar the Scribe [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/images/eleazar.jpg)

The martyrs, therefore, died so that the nation would survive the crisis. Their deaths were the means by which the enemy was defeated and the land was purified of pagan contamination. They now “stand before the divine throne and live the life of the blessed age” (4 Macc. 17:18). Having given over their bodies to sufferings they were “deemed worthy of a divine inheritance” (4 Macc. 18:3). In other words, they suffered, they died, they were raised, they live in the presence of God, and they have inherited the age to come, or some such.

The “as it were” (hōsper) presumably signals the fact that the language was intended figuratively. No rationalising theory of atonement is required. Their deaths were simply the triumph of “godliness” over the “violence of a tyrant who wished to destroy the polity of the Hebrews” (4 Macc. 17:9). The sacrificial language is meaningful and relevant, but it is never more than a figurative way of talking about what actually happened.

The author of 4 Maccabees gives us a simple pragmatic explanation for the outcome: “Thanks to them the nation gained peace; by reviving loyalty to the law in the homeland, they pillaged their enemies” (4 Macc. 18:4).

The argument about Jesus

The argument about Jesus’ death is not pragmatic in quite the same way: it is not that Jesus revived or set an example of faithfulness in a way that inspired other Jews, leading to renewal and the salvation of Israel.

Rather, God so arranged things that Israel would be saved apart from the Law through the faith/faithfulness of those who believed that he had made Jesus Lord and Christ (cf. Rom. 3:21-26). The resurrection is the novelty here—the genuinely and unequivocally transcendent event that would transform the fortunes of God’s people and turn the ancient world upside.

But it still has to do with how things worked out historically.

My point is not that Jesus’ death was no different from—or no better than—the deaths of the Maccabean martyrs. It is that it is to be understood as a historical event, under historical conditions, as part of the same sort of historical narrative about the judgment and salvation of Israel. It was just a death. What set it apart, what made it effective in the apocalyptic narrative, was the vocation that preceded it—the explicit sending of the Son to the vineyard of Israel—and the tangible, witnessed vindication that came immediately after it.

For what it’s worth, I thought this was very clarifying.

Excellent article! I love your clear writing style and your desire to bring clarity into areas that have been unclear for so long!

Andrew,

As I said before, I like the historical angle. But I can’t buy the latent zwinglianism inherent in your interpretive approach. I agree that Jesus’ death was significant as a historical event, and I think any decent treatment of it must take this angle into account. But to say that it is not also efficacious in some other way seem a tad reductionistic and blunts the force of many passages which speak of the forgiveness of sins etc. These passages are not merely using a kind of literary device. They are outlining a change in God’s disposition toward mankind. The theological angle is just as important in this respect.

@Chris Wooldridge:

Do you want to suggest a couple of these passages to look at?

@Andrew Perriman:

Absolutely! Hebrews 10 and Romans 6 would both be good passages to consider. Just off the top of my head.

@Chris Wooldridge:

Thank you, Chris, for offering passages to test ideas against. I find it really helpful.

After reviewing them, it seems that Point 17 of Andrew’s post does a good job for me of handling Hebrews 10 as well as Ephesians. I also find that Romans 6 also makes more sense than ever reading it from the perspective of the blog. I see a strong connection to Peter Rollins’ writing about the nature of the Law as Prohibition and how it actually enslaves us to sin. When read narrative-historically, Romans 6 talks about being freed from that enslavement quite clearly.

Of course, I’m open to additional thoughts.

@Chris Wooldridge:

Thanks. I’ll resist the temptation to answer off the top of my head. I’ll get round to it maybe next week.

@Chris Wooldridge:

Had a look at Hebrews here.

“8.Theological accounts of the “cross” that fail to reckon with the Jewish-apocalyptic narrative are more of a nuisance than they’re worth.”

Accounts of “Jewish-apocalyptic narrative” that fail to reckon with the fact that “Jewish-apocalyptic narrative” is just post-scriptural folklore seem to justify the NT ftom an OT perspective, but in reality do not.

In other words, my major problem with what you are calling a “historical-narrative” approach, is that it puts post-scriptural speculation and mythology on the same plane as (nay, even higher than) scripture itself. The approach you’re using towards the OT is like treating the Book of Mormon and The Shack as of higher authority for Christians than the NT. Its an illegitimate way of looking at ancient Judaism.

Furthermore, the NT itself plainly claims to be a fullfillment of the OT itself(!) not just of later Pharisaic speculative mythology. So even if the NT succeeds in fulfilling later mythology (which is debateable), that does not save it from the fact that it fails to do what it itself actually claims to do.

It was just a death. What set it apart, what made it effective in the apocalyptic narrative, was the vocation that preceded it—the explicit sending of the Son to the vineyard of Israel—and the tangible, witnessed vindication that came immediately after it.

When you speak of “vindication”, do you have in mind …

«Let all the house of Israel therefore know for certain that God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified.» (Acts 2:36)

… this verse? (Maybe also Phil 2:9-11?)

Recent comments