In his talk on Daniel 4 this week Barney made passing reference to the “biblical mandate to bring justice by changing the structures of society”. I forget exactly the point he was making, but it would have had something to do with Daniel’s words to Nebuchadnezzar after interpreting the dream about the tree that is cut back to the stump:

Therefore, O king, let my counsel be acceptable to you: break off your sins by practicing righteousness, and your iniquities by showing mercy to the oppressed, that there may perhaps be a lengthening of your prosperity. (Dan. 4:27)

The talk was excellent and stimulated good conversation. But I’m not sure about that throw-away comment. Is there really such a “biblical mandate”? Is it clearly taught in scripture that a central task of the church is to go and bring justice by changing the structures of society?

There’s no question that God’s people are expected to demonstrate justice internally, in the various forms of their shared community life.

The Law of Moses mandated for Israel distinctive patterns of righteous and just behaviour. It was a primary responsibility of judges and kings and other leaders—right down to the chief priests and elders of Jesus’ day—to uphold righteousness and justice. And when things got out of kilter, as they inevitably did, the prophets drew attention to the fact, called Israel to repentance, and warned of national disaster if those responsible failed to put their house in order.

But it can hardly be claimed that the Jews programmatically engaged in—or were encouraged to engage in—social activism outside of Israel. The most that can be said, I think, is that if they had kept the commandments and walked in the ways of the Lord, they would have modelled righteousness and justice for the surrounding nations.

The prophets were not indifferent to the fact that great injustices were done in the world around, but the response was invariably to announce that the God of the whole earth saw these things and sooner or later would act as a judge or a king to punish wickedness and put things right.

For example, God hears the “outcry against Sodom and Gomorrah”, two angels come to investigate, the threatened homosexual gang rape reveals to them just how bad things had got, and so the destruction of Sodom becomes the paradigm for divine judgment on social injustice throughout the Bible (cf. Ezek. 16:49).

Jeremiah’s letter to the exiles is often cited as an argument for mission as social transformation. But Jeremiah is concerned primarily with the material well-being of the Jews. On the one hand, they should plant gardens and eat the produce; on the other, they should seek the welfare or shalom of the city because “in its welfare you will find your welfare” (Jer. 29:5-7). This is not mission; it’s self-interest.

How many people who hold up Jeremiah’s letter as a model for social engagement also mention the lengthy and conventional proclamation of judgment on Babylon in chapters 50-51? Babylon will prosper only as long as YHWH means to keep his people there. But then the city will be attacked, plundered, punished because “she has sinned against the Lord” (Jer. 50:14). The ruins of the city will become a home for hyenas and ostriches—social transformation of a sort, I suppose.

Returning to Daniel 4: perhaps having regained his right mind Nebuchadnezzar made a point of practising righteousness and showing mercy to the oppressed. But this makes Daniel an agent of social transformation only insofar as he gave Nebuchadnezzar a theological framework for understanding his dramatic experience. It’s significant, and perhaps a powerful model for Christian engagement in the political sphere today, but Daniel is simply speaking on behalf of the God who is sovereign over the whole earth.

Would we call John the Baptist a social activist? He tells the crowds to share their clothing and food. He tells the tax collectors not to take more than is permitted. He tells soldiers not to “extort money from anyone by threats or by false accusations” (Lk. 3:10-14). But this is a call to internal reform, and in any case the basic message is that the axe is already laid to the root of the fruitless trees, that the Lord is coming with his winnowing fork in his hand “to clear his threshing floor and to gather the wheat into his barn, but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire” (3:17).

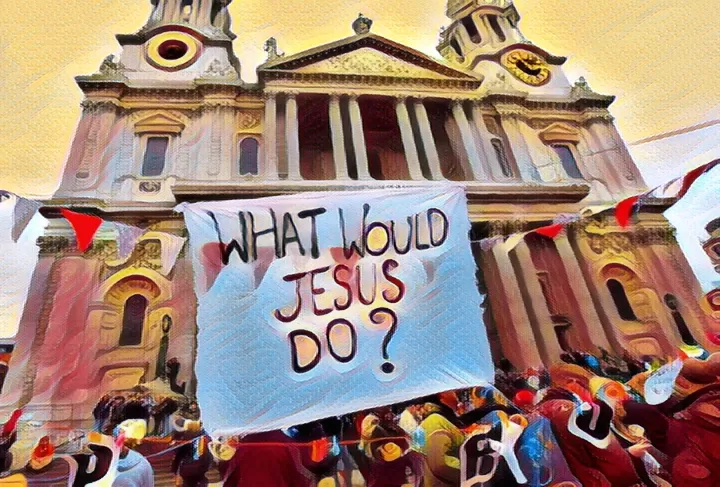

Jesus’ mission to Israel had nothing to do with social transformation. It was too late for that. The “kingdom” message was that unjust Israel was facing destruction. John had been the last of the prophet-servants sent to the mismanaged vineyard of Israel in search of the fruit of righteousness, and the wicked tenants had killed him. Now God was sending his Son, and they would kill him too. What would the owner of the vineyard do? The chief priests and the elders of the people knew the answer: “He will put those wretches to a miserable death and let out the vineyard to other tenants who will give him the fruits in their seasons” (Matt. 21:41).

What did Jesus do in the temple? He overthrew the tables of the money changers and the seats of those who sold pigeons as a symbolic gesture—the priests had turned the temple into a den of robbers (Mk. 11:15-17). But reform was out of the question. The message was clear: the whole temple system was about to be destroyed (cf. Jer. 7:8-15).

Certainly, Jesus healed the sick and demon-possessed and fed the hungry in Israel, but always miraculously, by the power of the Spirit, and as a sign that a much more significant intervention of God in the history of his wretched and tormented people was at hand.

He set high moral and religious standards for his followers to set them apart as an eschatological community that would survive the coming storm of God’s judgment against Israel. But I think we search in vain for anything that could be construed as a mandate to bring justice by changing the structures of society.

The apostles who took the good news of Jesus’ resurrection beyond the borders of Israel were fully aware of the depravity and wickedness and unjust social structures generated by the idolatrous culture of the Greek-Roman world. But they did not set about organising teams of passionate activists who would work to bring justice by changing the structures of society.

What they did was to establish communities of people who believed—against a tide of popular opinion that would come in before it went out again—that the God of Israel had raised his Son from the dead and that the future would be very different as a result. Sooner or later God would judge his own people. Then he would judge the nations. Or rather Jesus would carry out that judgment on God’s behalf and rule over the nations in the new age that would follow it.

If bringing justice by changing the structures of society was to be part of the mission of the church, you’d think that there would be some evidence for it in the book of Acts—a missional text if ever there was one. But there isn’t. What drives the mission in Luke’s narrative is the proclamation that Jesus has been raised from the dead and given an authority higher than that of Caesar. This is the message preached at Thessalonica, for example (Acts 17:2-7), and when Paul later writes to the church, he commends them for having turned from idolatry to serve the living God and wait for his Son from heaven, who will deliver them from the wrath to come (1 Thess. 1:9-10).

Paul urges the church in Rome to respect the governing authorities and pay their taxes as a strategy for surviving opposition and persecution (Rom. 13:1-7; cf. 12:14-21; 13:11-14). Peter writes to the “elect exiles of the dispersion”, instructing them to be “subject for the Lord’s sake to every human institution, whether it be to the emperor as supreme, or to governors as sent by him” (1 Pet. 2:13-14). These are the New Testament equivalents to Jeremiah’s letter. This is how you should live well in a hostile pagan culture-until your exile is brought to an end.

But finally Rome is denounced for its idolatry and social injustices: kings have committed immorality with her, merchants “have grown rich from the power of her luxurious living” (Rev. 18:3). Rome is just another Babylon—“Fallen, fallen is Babylon the great!”—and will be brought down. It will likewise become “a dwelling place for demons, a haunt for every unclean spirit, a haunt for every unclean bird, a haunt for every unclean and detestable beast” (18:2). At no point does John suggest that the churches should work for social transformation across the empire.

The biblical model for social transformation is a long-term catastrophic or eschatological one. Only rarely does a city get advance warning of the coming judgment of God on social injustice and repent-the response of the government and people of Nineveh to the begrudging preaching of Jonah is the exception rather than the rule.

The argument of the New Testament is also that God will judge the nations at some point in the historical future. The churches were not passive bystanders in the eschatological narrative. They had a crucial role to play. On the one hand, they proclaimed the coming reign of God over the nations. On the other, through the power of the eschatological Spirit they enacted in the present, in community, in concrete ethical and religious terms, Jew and Gentile united in Christ, the life of the post-pagan age to come.

Inevitably, embodying that new life in the build-up to God’s judgment on the nations would have had an impact on society. But that was a spin-off effect of doing things right among themselves. This is the force of Peter’s words to the Jewish-Christian diaspora in Asia Minor: “Keep your conduct among the Gentiles honorable, so that when they speak against you as evildoers, they may see your good deeds and glorify God on the day of visitation” (1 Pet. 2:12).

So it seems to me that the biblical mandate in the broadest terms is to proclaim, according to the historical context, the sovereignty of God—not least over the historical condition of his own people—and to interpret the world on that basis.

This is not an argument against either “personal evangelism” or social activism. But we too easily set the two in opposition to each other and then we let that tension pull mission apart. The lesson to be learnt from scripture, I think, is that neither personal salvation nor social activism makes much sense as mission without the containing narrative about God in history.

That is as true now as it was for Daniel or John the Baptist or Jesus or Paul or Peter or John the apocalypticist. But we are tongue-tied, inarticulate. We don’t know how to say it.

I think the narrative is essential as you say, but the example is meant to be formative for others as well as protective for self and the group of those who are our immediate ‘selves’ whether this be family, church, city, state, or nation. Parochialism of any sort cannot exist in the presence of God. Parochialism and its national expressions, or the corporate expressions that are trans national, are simply self-serving and without transcendent value. They are without submission to the God of the spirits of all flesh. God is of no account for them, so they fight or abandon their proxy wars and destruction of others at will. Will the day come that people can be ‘neath their vine and fig tree and live at peace and be unafraid? So that everything that has breath will praise Yahweh — the musical instruments as well as the singers and players.

We have a serious responsibility to the intent of the narrative of Israel — which does indeed provide the canonical example of faithfulness and therefore of the obedience to which all nations are called. One assumes of course that we readers can distinguish the desirable part of the example, the good as opposed to the evil. It is remarkable that in these days, the human virus on the surface of the earth is still learning the first lessons in the Bible — the complexity of male and female and the distinction between good and evil.

Bob, I’m not sure I see how this is a comment on this post.

@Andrew Perriman:

Well, in view of the follow-on comments, I’m not sure why you’re not sure. Are you questioning me as a teacher or as a pastor?

re social justice, the job of our saltiness is to stimulate kindness in the bureaucracy. I have seen it demonstrated in Canada over my lifetime, and seen it lost — due to narrow government policy and that influenced wrongly IMO by so called ‘Christian right’ thinking. It is most obvious by studying the prison population and rehabilitation programs. The one who fears God of Psalm 112 would not act that way. The saints binding kings of Psalm 149 equally would bind them in mercy. For me, the governance mechanisms of our ruling of each other are the thrones, dominations, and principalities that we are to deal with in faith. The may be good angels or bad ones. And we must judge and bind with הסד.

re the function of the Churches (and of God), I would take Ephesians 2:15 as my starting place (if I have to read the NT). God is creating a new man out of a divided world. The one new man is the fullness of the new creation in and through the death of Jesus. It includes all humanity and it excludes all self-interest (aka idolatry). God forbid we should simply create a new wall of separation.

The relationship of the one to the many is very clear in many parts of TNK. It redefines for most Christians the idea of who ‘the son’ is, if we read the OT closely.

This discussion seems wide ranging enough to absorb my comment. Hoping I am off target….

hoping I am not too off target :) O typos

Good thoughts. But Psalm 149 is a song of fierce eschatological expectation. It reinforces my basic point, which is that the biblical vision is not one of progressive political transformation but of eventual judgment—and here, seemingly, in martial terms. Of course, we would like to think that kings and nobles may be bound by mercy, but that is not what is expressed here.

@Andrew Perriman:

I would disagree that mercy is not in view here. The ones who are doing the binding are the חסדים, the ones to whom mercy has been shown. There is no place for vindictiveness in this reading of the narrative of the Psalm. I’m sorry but this needs a book-length response. It is the reason I wrote Seeing the Psalter in 2013. 525 pages of analysis of this very problem of our misreading of imputed violence in the OT. We must not fail to see the narrative of the Psalter itself. It is not a random collection of poems.

I agree with you completely that narrative is critical. Words by themselves — verses by themselves — are sticks that pierce without healing. I would point out also that the OT is a song from start to finish. A song requires that we see the beauty of one note only in its phrase and in the structural context of its surroundings — both near and far.

Tongue tied and inarticulate indeed. We need your ongoing help Andrew to understand the narrative and shape our mission accordingly.

Andrew,

thanks for that. Very well put. I’ve been pondering that for a few years now and thinking alone the same lines. I think another relative scripture reference is 1 Thess. 4:1-12; of course technically those instructions would be for the eschatological community.

-Rich

‘There’s no question that God’s people are expected to demonstrate justice internally, in the various forms of their shared community life.’ So well put, and, in a way, all that needs to be said. ‘Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father in heaven.’

Thank you, Andrew, for your kind words about my talk! There is much to agree with in your analysis. I appreciate your point that social activism becomes null and void when separated from the greater story of God’s mission to redeem the whole world. The initiative is God’s and the church is merely an instrument; to forget this is to divorce the theme of Justice from its rightful context in God’s story, with disastrous consequences.

But I am not sure that your article actually agrees with its title, when read carefully. Your article protests against social activism without the containing narrative, but not against social activism per se. This is consistent with the lesson drawn from Daniel 4:27. Within the narrative, it is precisely societal reform that would have saved Nebuchadnezzar from his punishment, despite his kingdom not being the kingdom of the people of God.

But it wouldn’t trouble me very much, even if it turned out that there was no direct biblical text that supported societal reform in a kingdom that not identical with the people of God. The early Church understood the message of the Bible, not as a rule-book, but as training in virtue. The essence of virtue is that, by steeping oneself in a way of thinking, one’s basic instincts are changed. One responds intuitively, at a sub-rational level, to new circumstances not explicitly addressed by the text or previously encountered by the community. As Paul says, “the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life” (2 Cor 3:4). In this way, the fact that there is “no explicit Biblical evidence” for something, does not mean that the spirit of the Biblical witness doesn’t extend to behaviours not discussed “according to the letter.”

In fact, the importance of going “beyond the Bible” is precisely the strength of the narrative-historical hermeneutic, which recognises that the story continues after the end of the Bible, and it is not our job simply to endlessly repeat, identically for every generation, the one moment in the story recorded by the New Testament. Instead, we must discern where we are in the story and creatively enact the spirit of the Biblical message in our own time, non-identically.

The wider sweep of the biblical story shows that the people of God had their own earthly Kingdom for a while, and then they didn’t. The Church was born in a kingdom not its own, and so the New Testament was written in a context where defining and preserving the new community was of tantamount importance. But later the people of God triumphed over Rome and the Empire was baptised. Then the people of God had an earthly Kingdom again, and they had to think about societal reform as internal house-keeping.

Now, once again, the people of God do not have an earthly kingdom. What do we learn from the basic principles of the Bible about how to act in a pluralistic society? You are right that we must “proclaim” the message of God’s judgment. But the gospel is not only a matter of talk, but of action. Based on the loud Scriptural refrain that God is just and he loves to see justice, there seems no clear reason for Christians to limit this passion for justice to within church communities only. Abraham is a blessing to the nations in many diverse ways, one of which is to hold up a standard of how the nations ought to act. Amos 1-2 proclaims judgment on other kingdoms for failing to act justly. If an Israelite happened to be living in Edom, should he/she not use his/her influence to bring Edomite society into conformity with God’s divine order? James 5:1-6 doesn’t seem too concerned with whether the oppressed are Christians or not. A righteous Christian politician will seek to establish justice as part of his/her earthly vocation. The Biblical story helps motivate him/her to see his/her work as part of a bigger narrative of redemption.

Many church traditions have felt it necessary to oppose ecclesiology and social transformation, as if emphasising one inevitably means neglect of the other. Reformed theology has been strong on social justice and weak on the nature of the church; Anabaptist theology the opposite; The Evangelical movement, being a grandchild of Reformed theology and Lutheran pietism, has historically been weaker in its understanding of the role of the Church in the economy of God’s redemptive action. I am passionate about bringing the two emphases together such that one does not eclipse the other. It has been achieved in the past and I believe it can be achieved again.

@Barney:

A solid response, Barney. Thank you. I’ll pick up on a number of your points. I hope it doesn’t come across as nit-picking. You do a good job of throwing my own argument back at me!

…the greater story of God’s mission to redeem the whole world.

I’m afraid this is another one of those fashionable theological assumptions that I’m inclined to question. I don’t see any reason to conclude from scripture that the mission of God is to redeem the world. There will be a final renewal (not redemption) of creation, but until then the mission of God, it seems to me, is to maintain a viable and credible priestly-prophetic servant people throughout the ups and downs of history.

Within the narrative, it is precisely societal reform that would have saved Nebuchadnezzar from his punishment, despite his kingdom not being the kingdom of the people of God.

Agreed, and I stressed in the post that it was ‘not an argument against either “personal evangelism” or social activism’. But as you said yourself, Daniel was not much more than a bystander in the process. I made the point that the interpretive Wisdom that Daniel brings to the situation is important, but this is a far cry from the sort of direct activism that often passes as engaging in the missio Dei.

The early Church understood the message of the Bible, not as a rule-book, but as training in virtue.

Which early church? The New Testament church? We are looking for a biblical mandate.

The most I would concede is that the New Testament church trained itself in virtue for the sake of the coming eschatological transformation. The ethical bar was raised very high out of fear of exclusion from the kingdom of God (cf. 1 Cor. 6:9-10). But there is little to suggest direct efforts to reform pagan society. The assumption, to the contrary, was that the form of that old idolatrous world was passing away (cf. 1 Cor. 7:31).

Arguably, it is just the sort of training in virtue demonstrated by Daniel that is missing in the “exiled” post-Christendom church. Progressive Christians engaging in social activism marks them out from traditional evangelicals but, ironically, it’s now an act of cultural conformity. Everybody’s doing social justice these days.

The biblical message is that God changes things, not that his people change things.

As Paul says, “the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life” (2 Cor 3:4). In this way, the fact that there is “no explicit Biblical evidence” for something, does not mean that the spirit of the Biblical witness doesn’t extend to behaviours not discussed “according to the letter.”

Are you sure that you and Paul are talking about the same thing? Paul is drawing a contrast between the old covenant carved in letters on stone and a new covenant written with the Spirit on human hearts. The difference between what the text says and what we prefer to think that it said (the spirit of the Biblical witness”) is another matter.

In fact, the importance of going “beyond the Bible” is precisely the strength of the narrative-historical hermeneutic, which recognises that the story continues after the end of the Bible, and it is not our job simply to endlessly repeat, identically for every generation, the one moment in the story recorded by the New Testament. Instead, we must discern where we are in the story and creatively enact the spirit of the Biblical message in our own time, non-identically.

Very well stated.

Based on the loud Scriptural refrain that God is just and he loves to see justice, there seems no clear reason for Christians to limit this passion for justice to within church communities only.

That’s putting it negatively (“no clear reason… to limit”). Is there a clear positive reason or mandate for the church as church —as that priestly-prophetic people—to pursue justice in the wider society?

Why not do what Daniel and his mates did? At great risk to themselves, they stuck to their own ethical and religious standards out of loyalty to the covenant. That integrity gave them the opportunity to interpret Nebuchadnezzar’s dreams and affirm the sovereignty of the creator God. And they expected God to act in the future—to rescue them from death, to humiliate Nebuchadnezzar, to establish his own kingdom in place of the great empires. No doubt they did their admin work well, but there is nothing to suggest that they felt obliged to pursue social reform in Babylon.

I have a lot of sympathy for your argument and probably would agree with it—but cautiously. It seems to me that scripture prioritises the prophetic perspective on the action of God in history. My concern is that mute or mumbling Christian social action in the end only reinforces the secular-humanist narrative.

Abraham is a blessing to the nations in many diverse ways, one of which is to hold up a standard of how the nations ought to act.

Precisely my point—and John Shakespeare’s above. Part of my argument in The Future of the People of God: Reading Romans Before and After Western Christendom is that Paul regarded the synagogues as a failed benchmark of righteousness that would be replaced by the churches as a successful benchmark in the Spirit, by which the pagan world would be judged.

Perhaps the real issue here is reform of the church, not reform of Western society.

If an Israelite happened to be living in Edom, should heshe not use hisher influence to bring Edomite society into conformity with God’s divine order?

Perhaps, but I would expect him or her to do so in the tried-and-tested prophetic fashion of proclaiming the coming of YHWH in judgment and calling the Edomites to repent.

James 5:1-6 is likewise a prophetic call to the unrighteous to repent and change before God does something shocking: “Come now, you rich, weep and howl for the miseries that are coming upon you.”

A righteous Christian politician will seek to establish justice as part of his/her earthly vocation. The Biblical story helps motivate him /her to see his/her work as part of a bigger narrative of redemption.

Yes, but where I think the church is failing is in not providing the “prophetic” framework that makes sense of such individual actions. As I said, Christians are not the only people working for social justice.

Interesting discussion, for my take on this I offer the following:

The church is much more about Eph 4, a gathering, worshipping, equipping place demonstrating unity of believers. i.e. the church as an entity is a visible demonstration of what a collection of Christ followers look like.

It is individually that we wield influence, and it is this that we take (light, salt, leaven) outside of the gathering times of the church, having been equipped and encouraged into our day to day lives, jobs and careers. e.g. Joseph and Daniel

My concern about any discussion of the church as a societal activist is the dilution and possibly even the distortion of the core mission of helping build and disciple its adherents into their place, fully equipped and functioning as Eph 4:12~16

@Rob Kampen:

Yes, Rob. But Paul didn’t write Ephesians 4 as a stand-alone pamphlet, which then happened to find its way into the larger letter. It’s part of the apocalyptic narrative of the letter. I made the same point with respect to the teaching about marriage in Ephesians in my previous post. We don’t think we need a narrative today, so we have no interest in the New Testament narrative, and we end up with tunnel vision. We select a few texts that lend themselves to generalisation. Paul trained the churches with a clear and urgent eschatological outcome in mind; they were equipped for a historical purpose. Without a comparable sense of our own narrative context, our own place in the scheme of things, my sense is that we don’t know what we are training people for.

Hi Andrew, great post and discussion with Barney.

I would appreciate your thoughts on how you see specific historical Christian social activism in light of your understanding outlined in your post. Take Wilberforce and his anti-slavery activism as a case in point.

What value in the kingdom of God?

To what extent did that contain the narrative of God in history?

To what extent did it make sense as mission?

If you were Wilberforce, what would you have done differently?

Thanks, Andrew. Trying to translate what you wrote into a real life, albeit it historical, context.

However, I realise that being in a post-Christian context today might change things.

So, I’d also welcome you discussing the same questions but maybe applying them to a Christian leader of an anti-trafficking charity. I guess the questions then would be:

What value to give one’s life to such a task?

How can such activism contain the narrative of God in history?

How would that make better sense as mission?

If you were that Christian leader of an anti-trafficking charity that didn’t have the view point you’ve shared here BUT then came to understand and embrace your understanding, how might that change things for you?

Best wishes,

Paul

@PaulK:

Thanks, Paul. Excellent questions. I can only offer more questions and a few tentative and ill-informed answers in response.

Was Wilberforce reforming a Christian society or transforming the world outside the church? I think you’ve identified that problem.

Would slavery have been abolished anyway as being offensive to Enlightenment values? To what extent did the abolition movement succeed because it was an appeal to natural justice and the rights of man—in other words, to Enlightenment values—whatever the personal motivations of some of its leaders may have been?

I would argue that what is going on in the kingdom narrative at this time is that the Christian consensus is being overthrown by secular rationalism—arguably, a “judgment” on an ethically and intellectually complacent church, as I think Barney suggested in his talk. Christ is being dethroned. From that perspective, Wilberforce has proved to be an instrument of liberal humanism.

As for the anti-trafficking charity example…

For what it’s worth, I’m inclined to think that we are still at the stage where Christians are reacting against a narrow, stultifying, over-individualised evangelicalism and straining to capture and express something of the righteousness and justice of the creator God. I regard that as a work of the Spirit.

But inevitably the practical instinct, the pull of the Spirit, has got ahead of the theology—as is evident not least from the fact that we appear to have no better alternative to the social justice gospel than the personal salvation gospel.

The problem with holding up the abolition of slavery as “mission” is that in the end it got lost in the much bigger process of social and intellectual change that was going on in 18th and 19th centuries, for which the church can claim very little credit. The same risk is there for Christian anti-trafficking charities. What does that sort of activity say about our faith in the God who is in control of history?

I think that the narrative-historical hermeneutic is helping us to frame the justice instinct better, but we have a lot to learn. Part of the conversation in Harlesden went from affirming social engagement to panicking over personal salvation (I exaggerate) to recognising that what’s fundamentally at stake, and at the heart of our witness, is the sovereignty of God. I found that encouraging.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hi Andrew, sorry for a much delayed acknowledgement of your reply. I always appreciate that you take the time to reply. I also recognise that I come from a place of ignorance, relative to the conversationand contribution you bring — so I don’t always understand what you are saying, meaning or where that all takes is. But, as so think you say, we are in a state of flux — so it seems we are all in a journey of discovery. Hence me being keen to listen, ask questions, and try to learn.

I appreciated Emi’s questions here and your response in a new post, and Phil’s comments tothat post. Thank you all.

I feel more lost than I ever have before. No longer having a distinct purpose and mission, I have no idea what to do with my life, because there’s nothing for me by which to choose my actions. I cannot live a life that does not align with the higher meaning and purpose that must exist if a perfect, transcendent, all-powerful, all-righteous, and all-just divine Creator God exists.

You say that believing in and submitting to Christ allows one to become one of God’s new creation people. You also abide by the statement that the wages of sin are death. You have said that our mission is “to demonstrate through our existence the re-creative power of God.” You haven’t explained if non-Christians are for sure damned to death at the final judgment, or if there is a possibility that if their actions were good enough, their verdict could be of a kind other than death. This is absolutely essential to our mission, unless we believe that the salvation of people is not of greatest priority in God’s whole plan. If it is not, then I don’t know how I can believe in Christianity.

God’s love for people is present throughout the entire Bible, and God repeatedly acts to save His people, so it seems like I can say with confidence that within God’s priorities are the well-being and fates of humans. Therefore, if the well-being and fate of those outside of God’s people aren’t important to God, then God (and Christianity) seems exclusive and unfair. Those who joined God’s people did so because of literal, specific humans having acted to share Christianity with them, and so God’s lack of concern with anyone who happened to not get that opportunity seems unfair to me. It seems that in this case, God would be caring only for those who received the chance to be told about Christianity and cared for so they might choose to join God’s people. Accordingly, God would not be caring for others even though most of the others are only others because they did not receive the same chance.

I don’t think this is true, because God’s concern seems to be with the goodness of all of Creation, and Christ’s act of salvation enabled the inclusion of as many people as possible into the new creation people. How could it not be a priority in our mission to get as many people as possible to take the chance to become part of the new creation people, which realizes the goodness of all of Creation?

In this specific article, you emphasize that the sovereignty of God is the primary thing upon which our actions, faith, and community must center. In one of your comments you say, “The same risk is there for Christian anti-trafficking charities. What does that sort of activity say about our faith in the God who is in control of history?” This really throws me off. This to me implies that if we had greater faith in God and His control of history, we would not try to change injustices directly in front of us. I think we would become passive and useless people if we did this.

You have often said that we as post-Christendom and post-NT Christians must now find our new purpose and identity in this new context, culture, and historical time period. Does that mean there is no solid, definitive, conclusive answer to my question of what our mission is? How in the world do we find our new purpose and identity if Scripture as a result of being specific to a specific context/culture/history does not provide us guidance? Do we wait for a new revelation or addition to Scripture?

@Emi:

Hi Emi,

I’ve had a go at answering your challenging questions here. Don’t miss the comment from Phil Ledgerwood.

Andrew -

Have you read McKnight’s, Kingdom Conspiracy? I know he doesn’t take the historical narrative approach as far as you’d like, being more akin to Wright & Dunn, but he has a lot to say about God’s “kingdom” mission being for within the church. Then there is the opportunity to do for the common good in the world.

Anyways, in regard to our own prophetic-historical call in a post-Christendom era, could we identify our call as to be agents of social change in our own world, standing against the “powers and principalities” of our own day?

@Scott:

Yes, I’ve read Kingdom Conspiracy. I think it’s a good book.

…could we identify our call as to be agents of social change in our own world, standing against the “powers and principalities” of our own day?

Perhaps. But “powers and principalities” is New Testament language. What was the New Testament argument? Were the churches across the empire “agents of social change”? How does the whole story translate? Can it be translated? If not, what story do we need to tell about “powers and principalities”? Where does God come into it?

Recent comments