The basic thesis of Greg Beale’s A New Testament Biblical Theology is i) that the Old Testament gives us the story of how God “progressively reestablishes his new-creational kingdom out of chaos”; and ii) that this storyline is transformed in the New Testament inasmuch as Jesus’ life, death and resurrection have “launched the fulfillment of the eschatological already-not yet new-creational reign” (16, italics removed, statements abbreviated, other caveats may apply).

In short, he aims to develop a more or less comprehensive biblical theology controlled by a story oriented towards the “goal of new-creational kingship” (179). Note the merging of “new creation” and “kingdom”—I’ll come back to that.

I think that Beale is broadly right to say that “the doctrine of eschatology in NT theology textbooks should not merely be one among many doctrines that are addressed but should be the lens through which all the doctrines are best understood” (18). That sounds a bit like Greg Boyd’s reductionist insistence that everything needs to be interpreted in the light of the cross—the “lens” metaphor doesn’t help in that respect; but at least eschatology in principle brings the whole story into play.

The question is: how do we understand the whole story?

Beale defines his eschatology as “new-creational reign”, but what is the scope of that term (178-79)? Does it have reference specifically to the “apocalyptic notion of the dissolution and re-creation of the entire cosmos”? Is it about the end of the world, in other words? Or is it a more abstract “theological construct”—a container for hope in a general sense? Or are we talking more narrowly about Israel’s future and the characteristic set of expectations that went with it: vindication, return from captivity, judgment of the nations, etc.? The answer is all of them. He uses the phrase “new-creational reign” to refer to the “entire network of ideas that belong to renewal of the whole world, of Israel, and of the individual”. That sounds a bit indiscriminate for a start.

He then further refines his definition of eschatology by referring to N.T. Wright’s discussion of Israel’s idea of election in the New Testament and the People of God (259-60). Wright thinks that election operates on three levels, and Beale argues that this categorisation advances our understanding of “already-not yet eschatology”. I have to say, I’m not sure I follow his line of thought here, but that shouldn’t affect the critical points that I want to make.

According to Wright, Jewish covenant theology, especially in the second temple period, functioned as the “answer which was offered to the problem of evil in its various forms”. This worked at three levels; in Wright’s words:

1. At the large-scale level, creation has rebelled against the creator, but God “has called into being a people through whom he will work to restore his creation”.

2. At a smaller-scale there is the story of Israel’s sufferings and the faithfulness of the creator to restore his people.

3. At the individual level, which cannot be isolated from the other two, the “sufferings and sins of individual Jews may be seen in the light of the continual provision of forgiveness and restoration”.

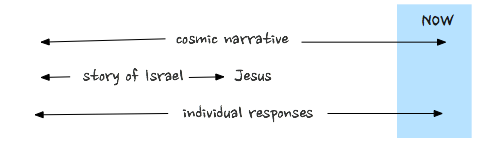

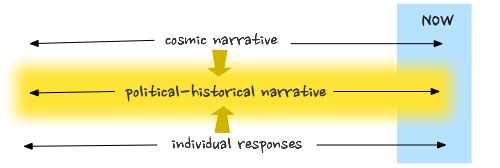

I think this differentiation between narrative levels is very helpful. It provides a clear methodological corrective to what I see as the basic failing of the current fashion for narrative theologies, which is that our modern, post-Christendom, globalising perspective blinds us to the mid-level narrative about Israel and the nations. The problem is that we assume that Israel’s story was fulfilled in Jesus and therefore the political-historical narrative came to an end. It doesn’t reach as far as the twenty-first century. So we have to jump to the higher level cosmic narrative and read everything on that basis. The story of Israel gets assimilated into the story of creation.

As I say, very helpful. But I think there are problems with the way the model is used—by Wright to some extent, but certainly by Beale.

1. I still don’t see how the first level argument about salvation works. Where in the Old Testament do we find the idea that YHWH will use Israel to restore his rebellious creation? For that matter, where in the Old Testament do we find the idea that God will restore his creation by any means? Abraham is not called to save the world. He is called to be the beginning of a people who will in theory walk in God’s ways and not rebel against the creator, who will serve God as a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex. 19:6). The nations will be blessed incidentally by the blessing of faithful Israel (cf. Joseph in Egypt), but there is no programme of cosmic salvation.

2. It seems to me that “kingdom” is not a cosmic but a historical-political category. My main complaint regarding Beale’s book is that he assimilates the kingdom argument about Israel and the nations into the cosmic new-creation category. The story of Israel is acknowledged but it has no real narrative or eschatological significance in its own right; it merely serves the large-scale story of the restoration of creation. I think this gets the biblical argument precisely back-to-front.

3. The dominant narrative in the Old Testament is the smaller-scale one—the story about Israel struggling to preserve and live up to its covenant relationship with YHWH in the midst of generally hostile nations. This is a political story: it has to do with the government of the people and with international relations. It is also, obviously, a historical story: it happens over a long period of time. But Beale seems to go out of his way to downplay the political-historical aspect. For example, in his discussion of the eschatological significance of Daniel 2 and 7-12 he merges the four kingdoms of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream into one so that they stand not for distinct political entities but for humanity in general, and he sees no reason to mention Antiochus Epiphanes (107-112, 191-94).

4. It is at the intermediate level that it makes sense to talk about elevated eschatological outcomes. Briefly put: Israel is punished for its rebelliousness, Israel is forgiven and restored, and YHWH will establish his rule over the pagan nations from Jerusalem, exercised by the king whom he has seated at his right hand. This is an extraordinary development, but it is a political development and it happens in history. It does not entail a transformation of the cosmos. The New Testament should be read as a continuation of this story: judgment against Israel, renewal of the covenant, and the rule of YHWH over the pagan nations, exercised by the king seated at his right hand. But by this stage apocalyptic Judaism has developed the conviction that there will be an ultimate vindication of the creator, beyond the fulfilment of the kingdom narrative, and John appends this hope to his narrative of judgment and vindication.

Finally, I think that it is important for evangelism, mission and discipleship today that we address the question of individual response and behaviour in relation to the full narrative of the existence of God’s people running right through to the precarious existence of the church in the secular West today. We are much to prone to talking in theological abstractions. We need to deal with our place in history.

Andrew, you wote: 1. I still don’t see how the first level argument about salvation works. Where in the Old Testament do we find the idea that YHWH will use Israel to restore his rebellious creation? For that matter, where in the Old Testament do we find the idea that God will restore his creation by any means? Abraham is not called to save the world. He is called to be the beginning of a people who will in theory walk in God’s ways and not rebel against the creator, who will serve God as a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex. 19:6). The nations will be blessed incidentally by the blessing of faithful Israel (cf. Joseph in Egypt), but there is no programme of cosmic salvation.

Alex: Here are a few scriptures that discuss ultimate Gentile blessing/inclusion/salvation to some extent:

“All the families on earth will be blessed through you.” Gen 12:3

“He will not falter or lose heart until justice prevails throughout the earth. Even distant lands beyond the sea will wait for his instruction.” Isaiah 42:4

“You will do more than restore the people of Israel to me. I will make you a light to the Gentiles, and you will bring my salvation to the ends of the earth.” Isaiah 49:6

“Surely you will summon nations you know not, and nations you do not know will come running to you, because of the Lord your God, the Holy One of Israel, for he has endowed you with splendor.” Isaiah 55:5

“Arise, Jerusalem! Let your light shine for all to see. For the glory of the Lord rises to shine on you. Darkness as black as night covers all the nations of the earth, but the glory of the Lord rises and appears over you. All nations will come to your light; mighty kings will come to see your radiance.” Isaiah 60:1-3

“The whole earth will acknowledge the Lord and return to him. All the families of the nations will bow down before him.” Psalm 22:27

“Nations from around the world will come to you and say, ‘Our ancestors left us a foolish heritage, for they worshiped worthless idols. Can people make their own gods? These are not real gods at all!’ The Lord says, ‘Now I will show them my power; now I will show them my might. At last they will know and understand

that I am the Lord.’” Jeremiah 16:19-21

“Many nations will join themselves to the Lord on that day, and they, too, will be my people. I will live among you, and you will know that the Lord of Heaven’s Armies sent me to you.” Zech 2:11

Or see the whole cluster of references Paul gives in Romans 15 after he says, in addition to coming to show the Jews God’s faithfulness, Christ came so “the Gentiles might give glory to God for his mercies to them”.

It seems that throughout the OT, and as the NT interprets it, there are places that the the suffering/vindication of the nation of Israel, and even its King, is seem to have a salvific effect that extends beyond Israel to the nations. And Paul interprets his Gospel in that light. Paul sees full inclusion of the Gentiles, their incorporation as sons of God, as one of the great mysteries of the Gospel that has been revealed.

Now I don’t really know exactly what you mean by “cosmic”, but I see it is tied to the theme of New Creation. If we are talking human-centered salvation, then the salvation brought is indeed cosmic as Paul sees us as gentile believers as already a New Creation in Christ, being conformed to his image. And there is definitely an already-not-yet aspect to this salvation that reaches out to the non-human created order in Paul. The ultimate glorification of believers will have ramifications for the created order, which will also be liberated/glorified in some sense:

“Yet what we suffer now is nothing compared to the glory he will reveal to us later. For all creation is waiting eagerly for that future day when God will reveal who his children really are. Against its will, all creation was subjected to God’s curse. But with eager hope, the creation looks forward to the day when it will join God’s children in glorious freedom from death and decay.” Romans 8:19-21

@Alex Dalton:

Thanks, Alex, for taking the trouble to respond in such detail. You’re right. The Old Testament tentatively and the New Testament categorically envisages the involvement of the nations in an eschatological salvation event.

The problem I have is with the distinction between a cosmic salvation and a political-historical salvation. I don’t in scripture see a salvation or redemption or restoration of the cosmos or of the whole of creation through the agency of God’s people. So, for example, at the end of Revelation the old creation simply disappears and a new creation comes into existence: it has nothing to do with the agency of the church. Romans 8 does not make the church the agent of the liberation of creation.

It is not in the large-scale cosmic story but in the smaller-scale political-historical story that we see dramatic transformation of the world through the agency of God’s people. Specifically, the punishment and suffering of Israel ultimately brings about the rule of God over the nations, and the New Testament proclaims that this has been achieved through the suffering of Jesus, who took the place of sinful Israel. The passages that you list all belong to this story; they speak of changes that take place not on the cosmic level but on the political-historical level, so in the Old Testament the ultimate vision is of an “empire” of YHWH centred on Zion to replace the empires of Assyria, Babylon, the Medes, and Greece.

The Bible uses “new creation” language for this, but in the Old Testament it is metaphorical and in the New Testament it refers to the transformative work of the Spirit. The resurrection of Christ, certainly, anticipates what I call an ontological novelty, a final new creation, but the the story about kingdom works itself out in this world, in the course of history.

Andrew, please read Paul carefully in Romans 8:19-21. He discusses the glory to be revealed as the result of our suffering. It explicitly says that the creation itself is metaphorically “waiting” for that ultimate glorification. For Paul, in many other areas, our glorification is the goal towards which the suffering of Christ is working itself out in us, through the Spirit. For Paul and many other NT authors, the scope of that glorification alone is cosmic in the sense in that we are being filled with all the fullness of God, growing up into the head of the body, partaking of the divine nature, and participating in, as much of a cheesy New Age connotation as this phrase has, a sort of “Cosmic Christ” — a *corporate* entity that we are organically and literally a part of. Schweitzer saw it, Sanders saw it, many of the best Pauline scholars now see it and are calling it different things, cashing it out in different ways. Call it mystical, call it cosmic, or call it none of those things, but it is definitely tied into the the theme of New Creation, and, if we can resist deification (which I don’t think we can), the concept here at least definitely involves us taking on the nature of a deity to SOME degree — being conformed to the image of the Son of God, who is the perfect image of God, and being enthroned with him to rule the cosmos. Surely this is an event of EXTREME cosmic significance, of the highest order and Paul portrays it as such. Furthermore, if, in order to be labeled “cosmic” on your view, something needs to incorporate the non-human creation, in a manner beyond the believers “in Christ” having complete God-like authority over it, Romans 8 broadens the scope of this cosmic enthronement/coronation to do just so.

The Creation is “waiting on this”, thus in some sense, dependent on it. It will be liberated from its bondage to death/decay as saints are given the kingdom. Yes it is an operation of God, yes it is through the Spirit, but it is God’s work IN the saints that is being done as much as through them out into the world — what Paul talks about when he says it is no longer him that lives but Christ living in him, travailing until Christ is formed in us, etc. Christ continues to operate as Paul, and all those in Christ, carry out the sufferings of Christ that remain. The saints will rule in a cosmic sense, not just political-historical one. They will be resurrected from the dead after their sufferings, be changed into an immortal glorified state, be enthroned with Christ, judge angels, receive all things, rule over the nations, etc. This is large-scale cosmic stuff impacting the order of the earth *and* the heavens, not just the earth, that Paul thinks actually is going to happen. As Paul, interepreted by Beale might say, the saints are already, though not yet, seated with Christ in the heavenly realms. We are already seated, in that Christ is enthroned and given all authority, and manifests himself as ruler in us through the Spirit which produces our obedience to him. But we are not yet seated, in that there is a final consummation of these things where our “flesh”and the creation itself are transformed into what Christ actually is, and I believe that is very obviously intended functionally and ontologically for Paul.

@Alex Dalton:

I’m short of time, so this is a bit rushed.

I agree that Paul says that creation is waiting for liberation from its bondage to decay. But he does not say that the suffering of sons of God is the means by which creation will be liberated. He does not say that the church is the agent of this cosmic redemption, if we want to call it that.

In my book on Romans (The Future of the People of God) I argued that the suffering community in this passage is not the whole church as we know but the persecuted and martyr churches of the early period. See also this post. This is the community that will be vindicated and glorified as Christ was vindicated and glorified—in Revelation 20:4-6 it is very clearly the martyrs who will be raised in a first resurrection and reign with Christ.

But however we read it, Paul does not make it the mission of the church to restore creation. Suffering creation hopes to experience the same glorification that awaits the martyrs.

This is basically why I disagree with the sort of christological inflationism that you describe. Paul affirms a powerful and comprehensive union between Christ and the suffering church—it goes back to his Damascus road experience. And he certainly believed that Jesus had been given an authority and status superior to all other powers in the cosmos.

Perhaps there is also a sense that the risen Christ, as new creation, embodied in himself the final renewal of the cosmos—I’m not sure. But in any case, this is far from being, in my view, the dominant conception. What dominates is the historical-eschatological argument about persecution, suffering, judgment, vindication and kingdom. The “cosmic Christ” argument seems to me just another way of ignoring the apocalyptic specificity of Paul’s vision—another way of compensating for the failure to keep the smaller-scale narrative up-to-date.

If you want to point to some other texts that support the “cosmic Christ” argument, I’d be happy to pursue the point further.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hi Andrew — you wrote: I agree that Paul says that creation is waiting for liberation from its bondage to decay. But he does not say that the suffering of sons of God is the means by which creation will be liberated.

Alex: So I have Beale’s book but haven’t read it yet. Where does he say that the sons of God will themselves liberate the material creation?

Andrew: This is the community that will be vindicated and glorified as Christ was vindicated and glorified—in Revelation 20:4-6 it is very clearly the martyrs who will be raised in a first resurrection and reign with Christ.

Alex: I just purchased your Romans commentary. I’d like to see you make this argument. Firstly, this limited scope doesn’t really affect any of my points here at all. But I am skeptical that Paul is only talking about “the early martyrs” here, and not the elect in general. Paul’s language is fairly broad/general — “those who love him”, those “called according to his purpose”, “those he justified”, etc. in these passages, and especially so as the argument continues into Romans 10: “…there may be righteousness for everyone who believes”, “As Scripture says, ‘Anyone who believes in him will never be put to shame.”, “the same Lord is Lord of all and richly blesses all who call on him”, “Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.”, etc. Paul leads into this kind of language, very smoothly without any obvious shift in the scope of referent, from the “the objects of his mercy, whom he prepared in advance for glory” in Rom 9, or the elect in Rom 8.

As for the “cosmic Christ”, I’ll write more as time permits here, but in my view the kingdom itself is cosmic, every bit as much as it is political-historical — these elements are inseparable. It is the rule of heaven breaking into the political-historical landscape of earth (“on earth as it is in heaven”, “my kingdom is not of this world”, etc.). I think you are trying to separate out aspects of the kingdom and the narrative that cannot be separated, and that Paul definitely sees in light of a larger picture that transcends the political-historical., then claiming these elements are a “dominant focus”. Hopefully I can say more on that, because I do not agree that you can even derive a dominant focus from Paul’s letters like this because of their incidental nature, and if you can, I think its much more of a cosmic narrative than political-historical at every level. We are going back and forth a bit because this “cosmic” term is left undefined.

You speak of the exaltation/rulership of Christ within your political-historical framework, and then tag on the word “eschatological”, but I can’t think of a worse candidate for being merely or even mainly political-historical. What could be more cosmic in scale, than the resurrection/recreation and exaltation of a human being to the right hand of God in an immortal glorified state, above all earthly *and* heavenly powers. What could be more cosmic in scale than God making the community of men to be the Temple of his dwelling — the house of his heavenly presence on earth? God’s presence is always bound up closely with covenant, kingship, Temple, etc. These are cosmic concepts even in the OT. The King is the vice-regent of God and his rule is co-extensive with God’s rule in many ways. The heavens are his throne, but his presence and rule reaches down into the earth, his footstool. He takes up a special residence in his Temple, etc.

The shift that takes place with the death of Christ, for Paul and other NT authors, is that the Temple system with its “dividing walls” of separation between people, and between man and God, has been done away with, and the access to and intimacy with God for both Jews and Gentiles has now been made possible. Again, this is cosmic stuff. There is nothing merely or mainly political-historical about what Paul calls “the mystery of the Gospel”, that has now been revealed: “Christ in you.” Christ lives in and works powerfully through Paul and other believers, via the Spirit. This union/participation theme is so prominent in Paul. This is hardly some minor issue. Pretty much every aspect of Paul’s theology — election, calling, Christian identity, atonement/justification, ethics, glorification, the sacraments — are rooted in a participationist framework.Have you read Sanders chapter on Pauline Soteriology in _Paul and Palestinian Judaism_ in a while?

@Alex Dalton:

Thanks for the careful engagement.

I don’t have Beale’s book handy at the moment, but Wright says that God “has called into being a people through whom he will work to restore his creation” (italics added). That would appear to mean that he sees the church as an agent of cosmic restoration, unless by “creation” he means something much more limited in scope, like “humanity” or “the nations”. I’m assuming Beale says or assumes something similar, but it needs checking.

I’ll let you decide about the validity of the claim in The Future of the People of God about the scope of Paul’s argument in Romans 8. But I don’t think it helps to pluck phrases out of context and claim that they have a general application. My view is that the whole letter, like every one of Paul’s letters with the exception perhaps of Philemon, presupposes more or less explicitly a pressing eschatological timeframe and the real prospect of persecution and suffering.

The justification/righteousness at issue in Romans is bound up with the call to trust the God who raised Jesus from the dead, even if this means ostracism and affliction, in the conviction that Jesus will eventually and in history be revealed to the nations as God’s Son. Historically speaking, the martyrs / suffering churches were publicly and realistically justified for their faith in Jesus when the empire was converted.

I would argue that Romans 10 is not about universal personal salvation but about the salvation of God’s people when they face eschatological judgment, i.e., AD 70—that is the whole thrust of the argument in chapters 9-11. Israel will be saved if people who believe that God raised his Son from the dead choose to walk—in Jesus’ language and following Jesus—the narrow path of suffering that leads to the life of the age to come.

I agree i) that Jesus has been given authority over all powers in the cosmos, and ii) that his resurrection anticipates a final new creation. But he has been given that authority, I think, for the sake of the ongoing “political” existence of the people of God. Jesus rules from heaven over and for the sake of his people on earth as they endeavour to fulfil their priestly-prophetic calling as God’s new creation people, especially when they face virulent pagan opposition. The argument and outlook are narrative-historically constrained.

I don’t agree that in the Old Testament the “King is the vice-regent of God and his rule is co-extensive with God’s rule in many ways”. YHWH establishes the rule of his king with respect to the nations (Pss. 2, 110); it is not in any sense a “cosmic” rule.

The removal of dividing walls, etc., by the death of Jesus is not “cosmic stuff”—at least, not according to my definition of “cosmic” (you’re right, we need some clarity here). It has to do with a human community living in relation to the living God. To call that “cosmic” is inflationary language. The “mystery” of the gospel, according to Paul, is simply that Gentiles have (unexpectedly, surprisingly) been included in the covenant people. Their inclusion, moreover, is a concrete sign that YHWH will sooner or later judge and rule over the nations through his Son.

I’ve read the participationist argument. I think it is over-applied. Participation in Christ is an eschatological notion: the churches participate in the suffering and vindication of Jesus, for the reasons given above.

Should there be a ‘cosmic narrative’ line at all? Isn’t the new cosmos merely an indicated end point? Whereas earthly history develops, and includes individual responses, we merely wait for the new cosmos coming, there are no changes happening gradually bringing it about. Or what?!

@davey:

That’s a good observation. It’s a beginning and an end, but not an intervening story. That said, the cosmic end has a bearing on how we view the present. The renewal of the microcosm of Israel is seen as new creation; and in the post-Christendom context, it seems to make more sense to think of the identity and missional purpose of the church in new creation rather than political terms.

@Andrew Perriman:

Here’s a take on things! The post-Christendom lifestyle of renewed Israel (Christians) can maybe be said to be aspirationally life as in New Creation, but given the exigencies of the present creation and the difficulties (impossibilities) in even imagining what the New Creation will be like, it looks to me like our (Christians’) inadequate ideas and capabilities regarding living (morally) are all that can be undertaken as living in New Creation. So, New Creation doesn’t look to have any guiding power for Christians, guidance looks to be already in operation in the sorts of ideas about living Christians have inherited from the tradition, with ongoing revisions as has always been the case.

@davey:

New Creation is really the only guiding power for Christians. For Paul is tied up with our co-crucifixion with Christ on the cross, and the defeat of the power of sin and death, the Resurrection life of believers, the believer as God’s Temple and house of the Spirit of God, the church as collectively God’s body, etc. Part of what New Creation looks like, the most important part, is us, and has already begun, and Paul makes much of this incorporating all of the above concepts. The New Creation that God has wrought is the lense through which Christians are to see other believers:

“Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation; old things have passed away; behold, all things have become new.” 2 Cor 5:17

The New Creation Paul speaks of is the very act of salvation that God has wrought, that trivializes that law: “Neither circumcision nor uncircumcision means anything; what counts is the new creation.” (Gal 6:15)

Part of being this New Creation for believers, is being the residence of God’s presence, and Paul appeals to this aspect of our new identity as body and temple, which he apparently teaches regularly and expects the church to understand, to guide ethical behavior (“Don’t you know that you yourselves are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in your midst?” 1 Cor 3:16; “Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ himself? Shall I then take the members of Christ and unite them with a prostitute? Never!” 1 Cor. 6:15). Far from our inadequate ideas and capabilities being our only recourse for moral development, as New Creation, God resurrects us, indwells us, and empowers us through his Spirit, conforming us into the image of his Son.

@Alex Dalton:

Well, ok, Christians are ‘renewed’, though the ontology of that is not explained nor evident, and what it might come to still needs to be worked out in practice. It looks like an empirical matter how well Christians do, and they don’t seem to do well. Some reliable ‘inner guidance’ is empirically what Christians hardly seem to have at all. In practice they have to use their minds and hearts and the (up for revision) traditions to figure out how they should be and what they should be about. In doing that, Christians do take different views.

@davey:

Hi Davey — I don’t think the word “renewed” alone really captures it. I am renewed after a nap, or a shower. God very literally indwells believers as a result of Christ’s death/resurrection/enthronement. If that isn’t an ontological change for human beings, I’m not sure what is. This is evident and its implications explained all throughout the Pauline corpus. See Volker Rabens’ _The Holy Spirit and Ethics in Paul: Transformation and Empowering for Religious Ethical Life_. He deals with the aspect of ontological change and the Spirit in his essays “Pneuma and the Beholding of God” and “The Holy Spirit and Deification in Paul: A ‘Western’ Perspective” — both available for download on his academia.edu page.

@Alex Dalton:

Thanks for the references, I’ve had a look. What I see is that select aspects of the ontology of ‘indwelling’ and such are discussed academically, with a scholarly opinion the upshot. All worked out by thinking and addressing, reacting to and developing the tradition, as I said. And, as to the main point, as far as I can see there is nothing about Perimman’s concern, that Christians need to work out what to do on the demise of Christendom. The latter is, again, a matter of thinking and feeling and considering where to go within a developing tradition. The “transforming” and such doesn’t give Christians any clue.

@davey:

For Paul, who addresses Christian ethics the most in the NT, the transformation is ontological, and makes all the difference ethically with being able to will the good, know the good, etc. That doesn’t rule out deliberation, and Paul encourages that in places as well, but in Pauline theology, God living inside the person and changing them, is essential. I can’t speak to the personal experience of modern day Christians; I’m sure they’ve all been very different and I would not want to speculate.

Recent comments