Reading Charles Freeman’s no doubt partial account in [amazon:978-1400033805:inline] of the development of Nicene orthodoxy makes you realize, nevertheless, just how entangled with the intellectual and political interests of Christendom the development of Trinitarian thought was.

I have argued that, historically speaking, the conversion of the Roman empire should be seen as the proper fulfilment of New Testament expectations regarding judgment of the pagan world, the confession of Christ as Lord, and the vindication of the persecuted churches. But this “coming” of the reign of YHWH over the nations led inevitably to a fundamental reorientation of the “Christian” mind. The church challenged the state over the question of who ultimately was in charge—God or the gods, Christ or Caesar. That’s the apocalyptic or political narrative. But the church was more than happy to collaborate with the Platonist tradition in Greek philosophy in the construction of a new Christendom worldview. That’s the ontological or cosmic narrative.

As a result, the central theological achievement of early Christendom—the precise identification of Father, Son and Spirit as co-equal, co-eternal persons sharing one divine substance, etc.—can be presented as a thoroughly problematic compromise between philosophical enquiry, political expedience, and biblical interpretation.

1. Theology at this time developed generally as an amalgamation of biblical narrative and speculative philosophy. Christopher Stead is quoted: “The reality of God, his creation and providence, the heavenly powers, the human soul, its training, survival and judgment, could all be upheld by the appropriate choice of Platonic texts” (144).

The language and conceptuality of the doctrine of the Trinity, in particular, appear to have been shaped to some considerable extent by neo-Platonism, though Freeman admits that this is a matter of scholarly dispute. In the early fourth century Plotinus had proposed a metaphysical system consisting of three entities: the One, the Intellect (which “presents the Platonic Forms to the material world”), and the World Soul. Each entity had a distinct hypostasis or personality but shared a likeness: “the ousia of the divine extends to the [three] hypostaseis, [namely] the supreme god, the nous, and the world soul”; and the word homoousios is used to describe the “relationship of identity between the three”. So here was “a vocabulary and a framework of ideas” (Henry Chadwick) that was deployed by the Cappadocian Fathers to “describe Jesus the Son as an integral part of a single Godhead but with a distinct personality, hypostasis, within it” (189).

2. Freeman’s narrative strongly suggests that Nicene orthodoxy finally won the day as much for political as for theological reasons; and the impression is given—no doubt this is also debatable—that the bishops were pressured into accepting it against their better judgment. Eusebius credits Constantine with having urged “all towards agreement, until he had brought them to be of one mind and one belief on all the matters in dispute” (169). Constantine’s need to determine the limits of tax exemptions for the clergy appears to have been a major factor (178). The suppression of Homoean Christianity, which rejected the word homoousios, and ratification of Nicene orthodoxy by Theodosius may be seen “in terms of the need to find symbols around which to define the unity of the empire and consolidate its counter-attack [against the Goths]” (195).

3. The difficulties of reconciling the formal metaphysical symmetries of Trinitarian doctrine with the complex, untidy narratives of scripture were—and remain—substantial.

The “startling innovations” proclaimed by Constantine at the council [of Nicaea], in particular the final declaration that Jesus was homoousios (of the same substance) as the Father, proved easy to attack on the grounds that they both offended the tradition of seeing Jesus in some way as subordinate to his Father and used terminology that was nowhere to be found in scripture. (179)

Freeman quotes the acerbic response of Palladius to Ambrose of Milan’s defence of Nicene doctrine in De Fide: “Search the divine Scriptures, which you have neglected, so that under their divine guidance you may avoid the Hell towards which you are heading on your own” (196-97). The triumph of Athanasius over Arius was arguably the triumph of rationalist theology over scripture—certainly as Freeman tells the story. The new orthodoxy was regarded both by its opponents and by its supporters (ironically) as an “improvement” on scripture (197). It also proved to be a major reason for the strengthening of ecclesial control over biblical interpretation:

It is certainly arguable that the declaration of the Nicene Creed forced the church into taking greater control over the interpretation of the scriptures and in doing so reinforced its authority over doctrine…. (198)

This was not all necessarily bad. I think that the political-religious-intellectual phenomenon that was western Christendom was inevitable and, for all its sins, probably defensible as an extension of the biblical narrative. But the question must now surely arise whether a doctrine—or the form of a doctrine—that is so closely associated with the intellectual and political interests of Christendom should not be allowed to collapse along with Christendom.

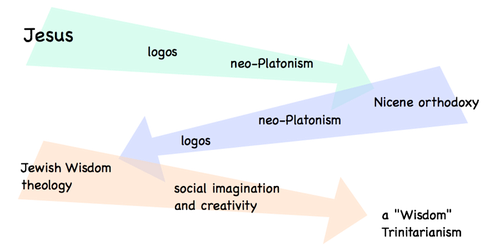

In order to give due weight to the apocalyptic character of the presentation of Jesus in the New Testament, I have sometimes suggested that the Trinity should be understood as essentially a narrative construct: Trinity is the story of God’s dealing with his people. But it might also be fruitful to retrace the path of intellectual development back through neo-Platonism and John’s intermediate logos theology to a practical and creational Jewish Wisdom theology.

Why not then develop a model of the transcendent relationship of the Father to the Son—that is the relationship that transcends or precedes the apocalyptic-political narrative about YHWH and the nations—around the dynamic, creation-oriented biblical notion of Wisdom, which is, after all, what the New Testament does?

This would have the effect of placing the apocalyptic story about Jesus within the bigger story of God and creation. But it may also give us a biblical language for God as Father, Son and Spirit that will address the enormous cultural-intellectual challenges that the church will face in the post-Christendom, post-modern era. Wisdom may have a transcendent character, but it also presupposes a very down-to-earth, Aristotelian engagement with the realities of life. A “Wisdom” Trinitarianism would find in the Jesus who always inaugurates a new world for his people the necessary resources of critical analysis, imagination and creativity not just to survive but to demonstrate the resilient potential of God’s new creation.

I guess that needs unpacking a bit….

The Trinity is excessive. It’s an appendage that had no place in the NT story to begin with. A mythical/metaphorical approach to the Incarnation (as per John Hick) and a Christ-event that reminds humankind of their privileged position of theophoroi or God-bearers (cp. JAT Robinson, John Shelby Spong, James Dunn) will achieve much, much more for the people of God than the Trinity caricature ever has. It’s overstayed its welcome for long enough.

“This was not all necessarily bad.”

I guess this all depends on where you are sitting! And at what time in history (where you might have to run for your life).

Have you read Freeman’s book 381 AD, Andrew? Maybe not yet. It does appear to have much of the same substance as the one you are reading now. I’ve been following the discussions on your blog for quite some time on this topic, simply because I am challenged by the Muslim community here in the United States to come up with some sort of explanation for Christian dogmatic “speculation” (the word used in a question to me by my Muslim friend: “Why do you Christians always speculate about everything in your doctrine?”)

As you say, it may be high time to dispense with it for something else, something more in line with regaining the narrative historical view:

” But the question must now surely arise whether a doctrine—or the form of a doctrine—that is so closely associated with the intellectual and political interests of Christendom should not be allowed to collapse along with Christendom.”

Mark

@Mark Nieweg:

I think it would be far more fruitful to simply recognize Trinitarian theology as a response to the particular questions and issues that it addresses, which were largely questions of creation, worship, etc, and not to think that it should be in any way altered or jettisoned.

@Daniel:

Hi Daniel,

At first I was inclined to respond to you with something like “Possibly, but not necessarily.” But, I’d be more interested in you filling out a little more about how the circumstance I am describing with my Muslim friend could benefit from your take on the issue. While I have some ideas myself, I am really more interested in getting at what the scripture’s — which he is familiar with — intention is in its portrayal of Jesus. He might even accept that the theology was an attempt to deal with those issues of creation and worship you mention, but would conclude that it failed in that endeavor, or at least threw truer answers off track. There are many Christians that would also agree with my friend.

At any rate, we live for the most part in a Trinitarian Christian world that will little tolerate any deviation from established dogma. For me, I won’t find myself anytime soon requiring it from those who can’t accept it (even if I don’t have a problem with it myself), as long as they can accept that Jesus is God’s Messiah who fulfills what the prophets spoke.

Mark

@Mark Nieweg:

It is refreshing to see how these issues can be discussed, and with it the needs expressed by some to discard the Trinity in favor of an understanding of God and Jesus the first Christians were very comfortable with.

Anyway, it is often heard that the Trinity was formulated to answer certain questions. That the Trinity was the necessary result of these questions is often accepted uncritically; as if those Gentile Christians simply had no other option, but to opt for the Trinity instead of Arianism. This is not necessarily so. The confession that emerged from Nicaea was not due to superior philosophical prowess and Scriptural arguments. Athanasius admitted that many after Nicaea were very uneasy with the alien formulations necessary to arrive at the Deity of Christ (De Decretis Chapter V, sections 19-21). The Arians had a very compelling case which also had much more solid scriptural support. The outcome was not a rational one. It had been pre-determined and had political muscle on its side to be inforced.

Christianity at large, even those who start to have their reservations on certain doctrines, esp. Christology, is very sentimental. The Trinity is cherished and adored on grounds other than the Scriptural and cultural reasons of the First Century. That being said, when a minister of a traditionally Trinitarian Church tells you “our people will be freed and enlightened when they discard the Trinity,” it is truly encouraging.

@Jaco:

Just to keep the Trinity simple, God is one in nature, three in persons, Father, Son and Spirit. So all we would need to do is the following: Were the Jews Monotheistic? Yes. Did the Jews say God is one? Yes. Are Father, Son and Spirit described as seperate personal beings in the bible? Yes. Are all three called God? Yes. Does the bible ascribe “God only” attributes to each? Yes.

@Doane:

I’d suggest that the Father, Son, and Spirit are distinct but not separate. “Separate..beings” strongly suggests tritheism, and the Bible describes the Father, Son, and Spirit as present in one another.

But I think your comment does get at a good point, that not everyone who believes that God is triune is invested in some highly speculative extra-biblical philosophy and jargon, and the conviction can be expressed in simple language. Before there were formal and tidy theological formulations there was the early church encountering God as Father, Son, and Spirit dynamically involved in their lives to bring forth the blessings of the new covenant.

@Brandon E:

Hi Brandon,

Have you seen Andrew’s post called “Trinitarian Community” located here: http://www.postost.net/2011/05/trinitarian-community? It came to my mind when you stated above the following:

Before there were formal and tidy theological formulations there was the early church encountering God as Father, Son, and Spirit dynamically involved in their lives to bring forth the blessings of the new covenant.

I’ve been following this blog for some time now, watching the engagement of many others with Andrew’s proposal that our scriptures should be taken in a more dynamic, narrative historical approach. While it may not upset many presumptive ideas brought to the scriptures by later theological reflection, it sure does feel like it could, unveiling a kind of departure on the part of that later reflection that masks the intent of the narrative. That is what I am exploring here. I am asking whether the church has really “nailed down” God in an ontological way, or set up a stumbling block for others on the way in their seeking after God.

If you have not already done so, take a look at the various posts here that address this topic. It is a whirlwind for sure, but a very educational one. Personally, I am challenged to not only a more humble posture of certainty as regards what “makes up God,” but also finding a breadth to scripture that helps address my own “contingent” situations, giving the hope found in Christ to others.

Mark

@Mark Nieweg:

Hi Mark,

I'm a newcomer to Andrew's blog and have read a good number of his posts to get his basic argument concerning the narrative-historical perspective, but I hadn't seen that particular post. I read it briefly upon your recommendation and will return to it more in depth later.

At this point the narrative-historical perspective Andre describes seems to me to be itself a model that--typical of models--will see and point out challenging things that other models won't and will miss/filter out other things that don't fit into it; but do I agree that an overdependence on theological-philosophical systems or constructs can distract us from the message of the scriptures. To take the present example, I do believe that God is "triune," but some regularly employ expressions like "one essence and three persons" or "one what and three whos" as if this really defines or explains God without problem or inadequacy. But the words "persona" in Latin and "hypostases" in Greek don't mean the same thing as the word "person" in modern English (which has developed to mean a separate/autonomous/independent consciousness) or even the same thing as each other, and the original formulations weren't intended to "explain God" as such. But the expressions are often used as if they do, and then we get the kind of anti-trinity reactions from people like Jaco in the comments asserting that "To the ancient Jew God was not an impersonal substance" (as if this is what is actually meant by the trinity) or "If a Christian were to be asked, 'How many do you worship as God?' His answer would be 'Three.'" Well, I'm a Christian and I would never answer "three." But I can see how Jaco would claim so when so much stock is placed into formulaic words--the words themselves, rather than realities they only fallibly attempt to describe and point to--as if they explain God/the trinity.

@Brandon E:

"Andre" should read "Andrew" in second paragraph. Silly typo, and apologies.

@Brandon E:

Hi Brandon,

I could not find the block formatting options to post this, but these are your words above:

"But the expressions are often used as if they do, and then we get the kind of anti-trinity reactions from people like Jaco in the comments asserting that “To the ancient Jew God was not an impersonal substance' (as if this is what is actually meant by the trinity) or 'If a Christian were to be asked, 'How many do you worship as God?' His answer would be 'Three.'" Well, I'm a Christian and I would never answer "three." But I can see how Jaco would claim so when so much stock is placed into formulaic words--the words themselves, rather than realities they only fallibly attempt to describe and point to--as if they explain God/the trinity."

I would not hang Jaco out to dry too readily. I've communicated with him several times, and if he does at times react to language used, and even though you are correct that many Christians use language as you state with which he can react - he is a competent exegete. I find as I explore his position, one that is not held only by him, but by other capable people as well, I am left wondering whether I am Trinitarian, not due to "objective" exegesis, but because I begin with that conclusion and exegete the scriptures from that very point of view.

At the very least, I am left asking whether our scriptures are as concerned as we are about the questions Christian theological history has brought to them. In that, I get the feeling we are missing what they actually are designed to teach us. Worse, those like Jaco who can hold their own, even if at times are found to be working off similar premises as other doctrinal positions, are excluded from Christian fellowship. Just by my considering him I am already at the margins, if not "out" completely. I think Jesus has something to say about that.

Mark

@Mark Nieweg:

Hi Mark, my intention was not to hang Jaco out to dry as much as it was to use a readily available example of how getting hung up on formulaic doctrinal expressions can lead us to having a misplaced kind of discussion. As I suggested, "person" in modern English doesn't mean the same thing as "persona" or "hypostases" (the latter two words don't even mean the same thing as each other and were originally chosen as neutral placeholder terms to refer to the Father, Son, and Spirit, not to define philosophically the difference between a "substance" and a "person" or an "essence" and a "supporting substance"), making the concept of a "3-self God" and "God" as an "impersonal substance" that Jaco is attacking something of a straw man, for it amounts to tritheism but not what it really means for God to be triune. However, I can understand how he comes by the concept given how far some Christians press the word "persons" as if it explains God without problem inadequacy.

Incidentally, what do you think is the message of the Bible?

@Brandon E:

Hi Brandon,

Good question! I've seen others challenge scholars like N T Wright, and even Andrew on this site, as to just what the message of the Bible is if they (and I) are questioning some very deeply entrenched beliefs. Here is a go at it; this is taken from the cover of a fascinating book by F.F.Bruce called "New Testament Development of Old Testament Themes":

In Jesus the promise is confirmed,

The covenant is renewed,

The prophesies are fulfilled,

The law is vindicated.

Salvation is brought near,

Sacred history has reached its climax,

The perfect sacrifice

Has been offered and accepted,

The great priest over the household of God

Has taken his seat at God’s right hand,

The Prophet like Moses has been raised up,

The Son of David reigns,

The kingdom of God has been inaugurated,

The Son of Man has received dominion

From the Ancient of Days,

The Servant of the Lord,

Having been smitten to death

For his people’s transgression

And borne the sin of many,

Has accomplished the divine purpose,

Has seen light after the travail of his soul

And is now exalted and extolled

And made very high.

Hope that "grabs" you as it does me!

Mark

@Doane:

But it is not as simple. And what “God” meant to the Jews was obviously NOT what “God” meant to the later anti-Semitic Gentile Christians. Who the Jews referred to as One God was not what the later anti-Semitic Gentile Christians referred to as One God. To the ancient Jew God was not an impersonal substance; He was a personal being and singular in that personality. Not so with later Christianity. So if a Christian were to be asked, “How many do you worship as God?” His answer would be “Three” contra the monotheistic confession of “One” Jesus and the other Jews would answer. To “ease out” (also requiring an arrest of critical thinking) the tension between worshiping more than one as God and monotheism, those later Christians tampered with the underlying machinery of “being” and “person,” finally forcing the wedge between biblical theology and fabricated later theology. The Christian believin in a 3-self God cannot, in all cognitive honesty, refer to God as a HE. To such a Christian, God is a THEM, realising operational polytheism.

@Jaco:

Jaco,

Believing in the trinity “is” simple. Its what is revealed about God in the scriptures. Its equally as easy as believing that God is eternal and has always existed. It’s what the bible says. Now, if you think God having always existed is somehow easier to understand than God being one in nature three in persons, id like to know how that is.

@Doane:

No, it is NOT easy. if it were, it would not have been the favorite doctrine of MYSTERIANISTS; nor would it have been the greatest bane of theological philosophers. Eternality IS simple and secondly, such eternality is EXPLICITLY and REPEATEDLY stated in Scripture. Not so with the Trinty invention, hence the absurdity of your comparison. Allegiance to a doctrine and the alignment of arguments to serve that doctrine has never been to mankind’s advantage. Hence the curse of the trinity.

@Jaco van Zyl:

Jaco,

Do you believe Jesus is a created being? Or an eternal being?

@Doane:

What I believe is not important. The Bible calls Jesus the Second Adam, which assumes being created. Since Jesus has a God, that by necessity renders Jesus not-God and therefore created. What is eternal is the concept of perfect humanity which was restored in Christ as the rerun of the Eden drama. So Jesus is historically a created being but intentionally eternal.

@Jaco van Zyl:

Thanks for the clarification. So Does the bible teach that Jesus as the second Adam existed before he was “historically” born? And if so, does that mean that Adam existed before he was “historically” born?

@Doane:

You’re welcome. We know, for instance, that the Torah was given, and that it was a legal system which emerged historically. But the ancient Jews also had a metaphorical way of understanding the “existence” of Torah and other entities (Paradise, Gehennah, Son of Man, Patriarchs, etc.). These entities existed “with God” even before creation and before their historical appearance on the world-scene. Notionally or intentionally they were “with God,” and reserved for the moment when God would reveal them in the world. The same metaphorical understanding should be given to the preexistence of Jesus. Not only was he intended in prophecy, he was also the one who was ultimately identified as Messiah — an entity which had a notional preexistence since eternity.

So to answer your questions, No Jesus did not exist before his human life on earth. But he was intended along with several other entities since time immemorial in a metaphorical sense.

@Jaco van Zyl:

Jaco,

Your statement that “Jesus did not exist before his human life on earth” flies in the face of of Jesus’s statments that “before Abraham was born, I am ()”, and “Isaiah saw his glory and spoke of him” in which is undoubtedly a reference to Isaiah 6, plus where Jesus prays to the Father to glorify the son “with the glory which I had with you before the world was”.

Have I understood these texts correctly?

Ron

@Ron McAnally:

Thanks Ron,

I don’t think what I stated (which is but a restatement of what several theologians have concluded) “flies in the face of Jesus’ statements,” and that for several reasons:

The Gospel of John is a theological text full of figures of speech, metaphor, Hebraisms and literary imagery which cannot be read in a literalist way. Jesus is claimed to have said, for instance, that his flesh and blood would be eaten, or that he is the bread from heaven, or that he is the brazen serpent, etc. These are all metaphors which point to a much more significant truth than merely the literalist reading of the text. Among the figures of speech is also prolepsis or anticipation which means that what is anticipated is stated as if it had already come to pass. Jesus is claimed to have said, for instance, “and the glory which You gave me I have given them.” (John 17:22). The certainty of the expected glory is stated as if it had been received already. There a several more examples of prolepsis in GJohn, but I think what I’ve stated sets the scene.

Keeping in mind the pattern of sourcing classical Jewish images and applying the typology to Jesus, as well as the overall genre of the Gospel, we understand that Jesus had been the intended one. The ego eimi in John 8:58 is a simple phrase of self-identification. It is NOT a name, as used in the text, nor is the natural use of it meant to convey historical or actual existence. Self-identification is its function, as can also be seen in John 9:9. So, knowing perfectly well that Messiah had notionally be reserved with God in heaven, Jesus self-identifies as the one as whom this figure had been revealed. This one has been reserved since times immemorial, hence his statement (and my rewording), “Since even before Abraham was born, I have been the intended one.” My rendering of the second clause in the present perfect is justified by the exact same grammatical construct seen in Jer. 1:5 LXX. The classical rendering of the text, as well as its Trinitarian understanding, do the text an injustice. If Jesus wanted to identify himself as the I AM of the OT, he would rather have said, prin Abraam egenesthe, ego eimi O EGO EIMI.

“To say that Jesus is “before” him [Abraham] is not to lift him out of the ranks of humanity but to assert his unconditional precedence. To take such statements at the level of “flesh” so as to infer, as “the Jews” do that, at less than fifty, Jesus is claiming to have lived on this earth before Abraham (8:52 and 57), is to be as crass as Nicodemus who understands rebirth as an old man entering his mother’s womb a second time (3:4).” — J. A. T. Robinson, The Priority of John, 1987, p. 384.

On your second point above, glorification of Jesus in the Gospel is primarily in his suffering. His execution was the moment of his glory, since the execution meant life and glory to his followers. John 3:14 has Jesus comparing is future execution to the lifting up of the brazen serpent in Exodus. Much more can be said about this, but that will do for now. With that in mind, one would ask, where in (deutero-)Isaiah does the writer(s) speak of the Messiah’s glory, particularly in his suffering? Certainly not in Isaiah 6! We do see it, however, in deutero-Isaiah, specifically in chapter 52:13-15 (LXX):

Behold, my servant shall understand, and be exalted, and glorified exceedingly. As many shall be amazed at thee, so shall thy face be without glory from men, and thy glory [shall not be honoured] by the sons of men. Thus shall many nations wonder at him; and kings shall keep their mouths shut: for they to whom no report was brought concerning him, shall see; and they who have not heard, shall consider.

So here again a prophetic text is used to confirm the eventual fulfilment in Jesus.

On your third point the same can be said. Since the Messiah’s glory had been reserved with God since times indefinite, Jesus now prays to God Almighty to grant him the glory He reserved for him (compare Matt. 6:1):

“Jesus asks the Father to give him now the heavenly glory which he had with the Father before the world was. The conclusion that because Jesus possessed a preexistent glory in heaven he must also have preexisted personally in heaven is taken too hastily.” —Hans Wendt, D.D., Professor of Theology at the University of Jena.

Hope it answered your questions.

@Jaco:

Jaco,

Thanks again for all the details. It seems as though John is re stating Genesis. Genesis uses a plural when saying, “let US create man in OUR own image”. Then John comes along, re states Genesis throughout all the book (while at the same time mirroring all of Revelation structurally) and says that the “US” was Jesus and the Father. Not as essence or idea or pre determined future glory. This is as hebraic as it gets. John answers this mystery. This puts Jesus as having pre existence does it not? If not, who is the “US” in Genesis?

@Doane:

Hi Doane,

Yes, the Gospel writer gleans from various religious and cultural themes in Judaism in a very creative, but not uncommon way. I do not think, however, that limiting the Logos-references merely to the Genesis creation does justice to the overall richness of the text. In Philo as well as rabbinic Judaism, the word or logos of God had no one-time appearance in the past and never again. God’s word continued to “incarnate” throughout history, at creation, in natural phenomena, weather patterns, etc., but especially when it took shape in the visions and moments of enlightenment of sages. This Gospel deals with the legitimacy of Jesus as God’s representative, as well as his superiority to every other Jewish hero (compare John 3:13 and the colloquial used of “ascending into heaven”). Several theologians have argued that the Prologue has nothing to do with Jesus’ birth or historical origin; it deals with the moment of Jesus’ calling as son and prophet and Messiah. The logos incarnated in this enlightened one who as a result depicted the One he represented more closely than anyone else. An interesting article on this can be read here:

https://www.academia.edu/3288395/John_1_Jesus_Creator_of_an…

But to answer your question on the Genesis text, here is an interesting commentary in the NET Bible (Trinitarian Evangelical project):

The plural form of the verb has been the subject of much discussion through the years, and not surprisingly several suggestions have been put forward. Many Christian theologians interpret it as an early hint of plurality within the Godhead, but this view imposes later trinitarian concepts on the ancient text. Some have suggested the plural verb indicates majesty, but the plural of majesty is not used with verbs. C. Westermann (Genesis, 1:145) argues for a plural of “deliberation” here, but his proposed examples of this use (2 Sam 24:14; Isa 6:8) do not actually support his theory. In 2 Sam 24:14 David uses the plural as representative of all Israel, and in Isa 6:8 the Lord speaks on behalf of his heavenly court. In its ancient Israelite context the plural is most naturally understood as referring to God and his heavenly court (see 1 Kgs 22:19-22; Job 1:6-12; 2:1-6; Isa 6:1-8). (The most well-known members of this court are God’s messengers, or angels. In Gen 3:5 the serpent may refer to this group as “gods/divine beings.” See the note on the word “evil” in 3:5.) If this is the case, God invites the heavenly court to participate in the creation of humankind (perhaps in the role of offering praise, see Job 38:7), but he himself is the one who does the actual creative work (v. 27). Of course, this view does assume that the members of the heavenly court possess the divine “image” in some way. Since the image is closely associated with rulership, perhaps they share the divine image in that they, together with God and under his royal authority, are the executive authority over the world.

Another option is that text may hark back to polytheistic times when the Most High God addressed his court of gods on his intention and invitation to create. This may have been incorporated into the culture and speech of ancient Israel which later took on monotheistic/monolatrous meaning, as the commentary above explains.

So no, I do not think that the writer of the Gospel or any of the other NT writers locate Jesus in that expression.

@Jaco:

You make some excellent points. For a long time I have had difficulty with the Chalcedonian and Nicean formulations of the Trinity. Are you familiar with any of the work done by Margaret Barker in this area? I found her article on The Second Person facinating; it can be found here (or http://thinlyveiled.com/barkerweb.htm).

Scroll down the page until you see the article linked on the left side of the page. She attempts to show that Yahweh was the son of the Most High God and that the New Testament believers worshipped Jesus like the OT believers did Yahweh.

I would be interested to know you take on this.

@Ron McAnally:

Hi Ron,

Yes, I’ve read some of Margaret Barker’s work. Which one of the articles on the site you link are you referring to?

@Jaco:

Name of the article is "The Second Person".

@Ron McAnally:

Hi Ron,

I read Margaret Barker’s paper and found it quite interesting. It had me reread some material on pre-Second Temple Judaism as well as Andre Lemaire’s book on Monotheism. I find her arguments and conclusions rather selective and incoherent, but I think it requires a more thoughtful response than what I can give here. Maybe an article in future, who knows?

I also find John Tancock’s response below rather slanted and polemical. The implications of his statements are numerous incriminating Jesus, his followers and early post-biblical Gentile Christians who wrote on Christology. Nicaea did NOT adequately answer the questions (at least not according to those who pushed for later and subsequent Councils) and those questions only exist because of certain irrelevant assumptions preempting those those questions. This typical Evangelical stigmatising is not surprising either, as if only JWs and Socinians deny the Trinity. (Goodness, my ideas have been shaped by non-trinitarian scholarship ranging from JAT Robinson, to John Shelby Spong, to James D.G. Dunn, Hendrikus Berkhof, Karl-Heinz Ohlig, to James McGrath and Maurice Casey). Medieval demonising and witch-hunting is still alive and well among those who need it to protect a Sacred Cow. Indeed…

@Jaco:

Jaco,

You mentioned non-trinitarian scholarship ranging from JAT Robinson, to John Shelby Spong, to James D.G. Dunn, Hendrikus Berkhof, Karl-Heinz Ohlig, to James McGrath and Maurice Casey.

Could you share some books these men have written on this subject?

Thanks,

Ron McAnally

@Ron McAnally:

Hi Ron,

Yes, Dunn’s Christology in the Making and his Did the First Christians Worship Jesus? are good volumes by him. James McGrath’s The Only True God, Karl-Heinz Ohlig’s One or Three?, JAT Robinson’s The Human Face of God and On the Priority of John, Spong’s The Gospel of John, Stories from a Jewish Mystic, Berkof’s Christian Faith is more a general theology textbook. And Casey’s From Jewish Prophet to Gentile God, although I think his reasons for rejecting John are circular.

Hope you enjoy these.

@Ron McAnally:

The trinity is an explanation in response to questions. A case can be made that Chalcedon over refined those explanations but Nices didn’t.t. can. I recommend a book…. In the beginning was the Logos by Paul. Pavao. he takes the line that Nicene orthodoxy reflects accurately the anti teaching about god but later formulations over refine and define. The questions that trinity answers still exist of course Arian theology is still alive ( Jehovah’s witnesses). As is later socinianism reflected say in Jaco s comments. There is. A veritable anti Trinitarian industry out there many of the voices despise mainstream orthodoxy and evangelicals and would love to see an abandonment of ‘trinity’. however the answers which nicea provided are today needed because the questions still exist. Likwise the challenge of Islam will not be met with being obscurantist about the trinity or retreating and using familiar Unitarian language? a robust explanation that Islam totally misunderstands the trinity! the ‘deity’. ‘Sonship’ and position of Jesus is what is required. whilst the declaration of Thomas t?hat Jesus is his Lord and his God is in the NT and that the baptismal And discipleship command is in Mthw 28v19…… I remain trinitarian because of the biblical material. .

@Jaco:

You wrote:

On your second point above, glorification of Jesus in the Gospel is primarily in his suffering. His execution was the moment of his glory, since the execution meant life and glory to his followers. John 3:14 has Jesus comparing is future execution to the lifting up of the brazen serpent in Exodus. Much more can be said about this, but that will do for now. With that in mind, one would ask, where in (deutero-)Isaiah does the writer(s) speak of the Messiah’s glory, particularly in his suffering? Certainly not in Isaiah 6! We do see it, however, in deutero-Isaiah, specifically in chapter 52:13-15 (LXX):

My response:

John’s statement that Isaiah saw the glory of Jesus should be seen within the entirety of Isaiah 6. We can see evidence of this in the references to the “blinded eyes and hardened hearts” that John cites. Therefore I remained committed to the idea that Isaiah saw the pre existent Messiah although I certainly would not deny that there was glory in his suffering.

Sorry to be so late in responding.

Peace,

Ron McAnally

@Doane:

You’re welcome. We know, for instance, that the Torah was given, and that it was a legal system which emerged historically. But the ancient Jews also had a metaphorical way of understanding the “existence” of Torah and other entities (Paradise, Gehennah, Son of Man, Patriarchs, etc.). These entities existed “with God” even before creation and before their historical appearance on the world-scene. Notionally or intentionally they were “with God,” and reserved for the moment when God would reveal them in the world. The same metaphorical understanding should be given to the preexistence of Jesus. Not only was he intended in prophecy, he was also the one who was ultimately identified as Messiah — an entity which had a notional preexistence since eternity.

So to answer your questions, No Jesus did not exist before his human life on earth. But he was intended along with several other entities since time immemorial in a metaphorical sense.

@Mark Nieweg:

If you are interested in Freeman's book, you might also like this one.

http://www.amazon.com/Jesus-Wars-Patriarchs-Emperors-Christians-ebook/d…

Recent comments