I read a couple of old articles this week responding to Scot McKnight’s book [amazon:978-0310492986:inline] from a Reformed perspective: Scot McKnight and the “King Jesus Gospel” 2: Points of Concern by Trevin Wax, and What God Has Joined Together: The Story and Salvation Gospel by Luke Stamps. Both agree with McKnight’s insistence that the gospel cannot be understood apart from the story of Israel, which I think is a pretty clear indicator of the impact that the narrative-historical hermeneutic has had on traditional evangelical/Reformed thinking. But they are troubled by the claim that the “plan of salvation” is not part of the gospel. They think that McKnight has overstated his case, in Stamps words, “by separating the story of Israel from the promise of personal salvation”.

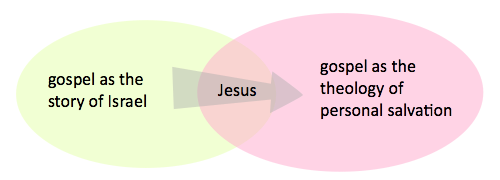

What strikes me about the critique is that the final position is structurally much the same as McKnight’s: the story of Israel finds fulfilment in Jesus, then we have personal salvation in Christ. The only difference is that whereas McKnight wants to associate the term “gospel” with the narrative part of the formula, Stamps and Wax would prefer to keep it with the theological part, as you would expect from the Gospel Coalition.

The problem is that this is a hybrid model. It’s a mash-up. The significance of Jesus with respect to Israel is determined narratively. The significance of Jesus with respect to the world is determined theologically—or more narrowly, soteriologically. Stamps even manages to locate the shift in Matthew 13, where the gospel which tells the story of Israel supposedly becomes the gospel of “personal trust in Jesus”. Nonsense. The story of Israel becomes a matter of personal trust in Jesus.

This is simply a compromise, a concession to the dominance of the theological paradigm; and I would suggest that in the long run it won’t work. If historical narrative takes us up to Jesus, then historical narrative can take us on from Jesus to the present day and beyond—and I think it will give us a much clearer understanding of the relation between gospel, the story of Israel, and personal salvation.

What has the gospel got to do with the story of Israel?

The Greek word euangelion (“gospel”) denotes the public proclamation of good news. The related verb euangelizō means “to proclaim good news”. To give a concrete example from the Greek Old Testament, following the death of Saul and Jonathan, David lamented:

Tell it not in Gath, and proclaim (euangelisēsthe) it not in the exits of Ascalon, lest daughters of foreigners rejoice, lest daughters of the uncircumcised exult. (2 Sam 1:20 LXX)

He did not want messengers going to the Philistines to proclaim the “good news” of the defeat. To “evangelize” was to tell people that something significant had happened.

Or was about to happen….

Isaiah imagined Jerusalem as a messenger who would proclaim the good news (euangelizomenos) to the cities of Judah that the God of the whole earth was about to come and deliver Israel from its captivity (Is. 40:9). He also pictured the messenger who would run across the mountains to proclaim the “good news” (euangelizomenos) to Jerusalem that YHWH reigned and would soon return to Zion to restore the fortunes of his people (Is. 52:7).

This is exactly the sort of prophetic announcement that Jesus made when he came to Galilee and said, “The time is fulfilled and the reign of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel” (Mk. 1:14-15). [pullquote]The good news was that God was about to act sovereignly as king, he was about to intervene decisively in the history of Israel.[/pullquote] Hold on to that.

It subsequently became apparent to the early church that the key moment in this intervention was the resurrection of Jesus from the dead—not as an isolated metaphysical or cosmic event but as a political-religious game-changer. Sovereignty over both Israel and the ancient world had been transferred from the true and living God to his Son, who would be judge and ruler of the nations. What Paul then did was take this message about what God was doing in and through his people first to the Jews of the diaspora and then, when the Jews rejected it, to the Gentiles.

So the gospel was a public announcement about an event in the history of Israel that was found to have massive implications for the peoples of the Greek-Roman world. If you take it out of that narrative context, it is simply not the same gospel—just as the American declaration of independence, for example, makes sense only in the context of the particular historical narrative of the emergence of America as a nation.

Then it was a matter of how individuals would respond to the particular historical announcement….

What did it mean for individual Jews or Gentiles in the New Testament period?

Jesus and his disciples proclaimed to the Jews that God was about to intervene sovereignly in the affairs of his people to deliver them from the consequences of their rebellion and to give them life. The response they sought from individuals was that they should repent and believe this proclamation. Some Jesus then called to follow him and become part of the evangelistic team, but that was a secondary response. Primarily, he urged Jews to abandon a broad road leading to the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple and find a narrow path of loyalty to YHWH that would lead to life.

So the gospel was the announcement about the coming kingdom of God. Salvation for Israel depended on the response of individual Jews to this message.

The situation for Gentiles across the empire was obviously different, but the basic arrangement was the same. Individuals became part of communities that had this conviction in common: they believed a story about Jesus; they believed that the true and living God had raised his Son from the dead and that he would come in glory to deliver them from persecution, defeat their enemies, and judge the nations. Because they believed this, they received the Holy Spirit, became part of this renewed community of the people of God, and waited for God to do what he had said he would do.

[pullquote]So again, the gospel was a public announcement made to the nations regarding the political-religious implications of Jesus’ resurrection.[/pullquote] It was good news that Jesus had been made Lord. It was good news that judgment was coming on pagan Rome. The “salvation” of individual Gentiles was what happened when they believed the announcement and acted accordingly—that is, they repented of and abandoned the pagan way of life and learnt to serve the true and living God.

Does the same gospel speak to us in the same way today?

One of the historical consequences of the long story of the people of God is that any person today, regardless of race, gender, or status, can enter into a relationship with the true and living God as a member of the renewed family of Abraham. Is that good news? Of course it is. Is it the good news that Jesus proclaimed to Israel under Roman occupation? No. Is it the good news that Paul proclaimed to a world sharply divided between Jews and Gentiles, a world dominated by the old pagan gods? No. But it is certainly one of the outcomes of this narrative.

Is it the best way of summing up the significance of the story of God’s people for the world today? Probably not.

Andrew,

Without asking you to provide someone with a “canned” approach to present the Gospel to unbelievers — how would the historical-narrative approach provide a message that could be propagated in the public square — today in our society?

I think the historical-narrative approach should do the historical-narrative thing:

- affirm the reality of the creator God and credibility of worship in an aggressively secular-materialist culture;

- confidently tell the story of God’s people, from Abraham to the present, with all its ups and downs, as a testimony to the faithfulness of God;

- draw the relevant conclusions from that story;

- paint alternative, unexpected futures;

- push people to respond, one way or another.

@Andrew Perriman:

This has actually aged fairly well considering where we are today in the world (and the US) no? Wow.

I agree with your approach. A couple of thoughts about our current state, and the future.

1. Perhaps it’s not quite right to suggest that modern society has rejected Jesus as Lord. Arguably, the very idea of a secular world, with a separation of church and state, etc, is a situation invented by Christianity. Maybe we’re entering into the “adulthood” of Christianity, and this entails a new sort of relationship with society. Maybe Christianity is gaining new ground, by adjusting the way it approaches the world.

2. It seems to me that the Jewish apocalyptic understanding of history wasn’t limited to one event, but was rather an outgrowth of the way God was understood to deal with the world. In the scriptures, Exodus is an apocalyptic moment, as are many other points in the Jewish story. The New Testament certainly offers a bigger apocalypse, but I see no reason to think it was the last apocalypse. If God is a God working in history to judge and vindicate his people, and to bring about justice, then we should expect more apocalyptic moments in the future.

(But future apocalyptic moments should be expected to run along the lines of the Old Testament prophets, not the lines of current apocalyptic story-telling, or rapture predictions.)

Both very interesting observations. I take your first point in principle, but I wonder i) does it apply more to the US than to Europe, and ii) how would you show that modern society has not (fully?) rejected the lordship of Jesus? I agree with your second point and with the caveat. I think we need to find a credible prophetic voice.

@Andrew Perriman:

I think by necessity, when looking into the more complex situation of the post-Christendom world, things will be harder to quantity. This doesn’t mean we’re no longer dealing with objective reality; it just means our tools for discussing things may need to improve, and may not quite be in place yet. (This is a general rule. It’s harder to talk about music buying and listening habits now than it used to be; mostly because the landscape has changed so much, it’s not clear what we should be measuring.)

The “separation of church and state” may be an American thing, but I think the secular arena (as it exists today) is something that emerged from within the Christian world, not in opposition to it. Even if, as it grew, it sometimes understood itself to be pushing back against Christianity, its growth was fueled by the values that had been engendered in Christendom.

As for the current status of the acceptance of the lordship of Jesus, several things may be considered:

1. To what extent is Jesus becoming a revered figure among other religious groups, and among non-religious people? To what extent has Jesus transcended the limits of traditional Christianity, and become central for many non-Christians?

2. To what extent is society progressively adopting and promoting the values it learned from Christianity?

3. To what extent is the current weakness of public Christianity really just a clarification of the way things have always been? It’s nice to be able to boast big numbers, but sometimes it’s better to challenge people, and weed out the non-committed. That’s not necessarily a loss; it may be a gain.

The difference I had in mind between Europe and the US was not so much the church-state separation as the greater secularization of Europe. We have state churches but practically speaking the gulof between church and secular culture is much greater than in the US. Arguably, European culture is actively disowning its Christian past and seeking to erase the last vestiges of it—though I’m sure it will look different to other people.

On #1: to the extent that’s true, aren’t we talking about the radically humane Jesus of the Gospels rather than the exalted Lord of the early church’s apocalypticism?

On #2. What use are values without narrative? Or without the very fussy God of the biblical witness?

I agree with #3.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

1. To my way of thinking, the exalted Lord of the early church’s apocalypticism arose from the profound experiences this church had with the historic (humane) Jesus. So if people are being drawn to that Jesus today (as conveyed through the gospels), then I don’t see a radical disconnect.

If apocalypticism naturally arose from these experiences the first time around, I wouldn’t be surprised to see it happen again. On the other hand, the church itself has tended to distance itself from the early church’s apocalypticism, so if others find the Jesus of the gospels compelling, but don’t pick up on the apocalyptic strain, that’s not an entirely unique reaction either.

2. As I see it, narrative is the way that we form and transmit values. The Genesis creation story reads like an inversion of the Babylonian creation story, precisely because it embodies such radically different values, and such a different vision of what it means to be human.

In our world, the Genesis story has all but obliterated the Babylonian story. There is no longer any competition; humans will never again tell themselves that they were created to be slaves. Instead, they will be drawn towards the depiction in Genesis 1: “made in God’s image”.

If that is the case, and this idea of what it means to be human takes on life outside of the story itself, then this is the victory of the story, not its defeat. It means that the story has dramatically succeeded.

This is NOT to say that we should downplay the narrative in favor of the values. Quite the contrary; we should embrace the narrative even more.

But what I’ve been arguing for here is the possibility that society has not fully rejected the Lordship of Jesus, that our moment is history is not one of decline or retreat, but of transition. Rather than looking at the world as having rejected our narrative, it may be more accurate to think that we’re seeing the side effects of our own success.

Just as the conversion of the empire resulted in some messy history, so the victory of the Christian narrative in the world may result in some things that don’t look very Christian.

Of course, time will tell.

Thanks, Micah. Good thoughts. As you say, only time will tell.

Micah I like your approach. Especially to the future and of recognizing the pattern of continual apocalyptic events. IGods apocalyic is more about a grooming process for us and Him in the world than about ending the world. As a Preterist idealist I see New Testament imminent apocalyptic to be about ending the age — not the world — in 70 AD. And i see resurrection as having been about the resurrection of Israel from the death of Adam, and the resurrection of “the dead” meaning the Old Testament saints who were in Hades, and bringing them to eternal life in heaven, (hence why it was always called an imminent resurrection of Israel not a far distant resurrection of christians!!) not about future bodies out of graves. Both of these views make the story and especially eschatology more about what God has done for Israel. And more about what we are grafted into by implication today (we are grafted into Israel not the other way around!). It gives us much more of the presence of God NOW a more hopeful future for the world and our role in it, and places the responsibility of spititually renewing the earth on US now, not on waiting for God in the future (present process oriented, not future singular event oriented). This is the trajectory of Christianity as more people learn about this alternative view. (preterism is a fast growing view as an alternative to the dominant destruction focused apocalyptic). And I believe this whole line of thinking that makes US a benefit and blessing to the world is a healthier approach in the long run. Interesting thought: “Jesus was Israel reduced to one man”.

Thanks Andrew. I’ve linked to this post from my blog: this is really interesting. As I say there, I’d love to see you join the dots from the Roman empire context through to proclaiming salvation today.

Thanks, Steve. That’s really appreciated.

I’ve tried a few times to “join the dots”, albeit in a very rudimentary fashion. For example:

Church as eschatological community (part 1)

Christendom: fulfilment or false start?

What we’re looking for here is not simply church history in the modern sense but something more like a prophetic retelling of that history that will help us to make sense of where we are today and what the future might hold. My book The Future of the People of God: Reading Romans Before and After Western Christendom was an attempt to show how the narrative holds the whole thing together.

(Steve Walton, by the way, has just started blogging at Acts and More.)

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew, thanks for the opportunity to eavesdrop on this fascinating conversation.

May I ask what is perhaps a tangential question, but it is to do with ‘joining the dots’…

What form might prayer take within the eschatological church?

@James Mercer:

Prayer will always take a variety of forms, but I would suggest that prayer shaped by a sense of narrative, of historical context, with a dimension of prophetic vision, would be appropriate. Many of the Psalms combine historical-prophetic narrative and prayer—Psalm 22, for example. Daniel 9:3-19 is a particularly good model. Jesus taught his disciples a thoroughly eschatological prayer, though the story-telling is implicit. Paul frequently prayers that the churches will remain steadfast through the eschatological crisis.

What fascinates me more and more is the seemingly irrecoverable notion of human beings to want to belong in one particular group or another, at the expense of “the other.” No theological interpretation of God’s Good News which leaves us “in” and others “out,” which converses in terms of “us” and “them,” can possibly be sound.

Obviously we have individual choices to make and choices lead to consequences, but we may not talk about “The Jew” or “The Born Again Believer” or “The Evangelical or Emergent” or “The Catholics” or “The Roman.”

Central to the Good News was and is the Kingdom of God, which nobody can claim for his own little exclusivist group. That Kingdom of God has everything to do with the “character” with which we go through life, i.e. with the nature of our fruit. Jesus said we recognize Kingdom resemblance by the fruit displayed. Do we emanate the character of the adversary: pushing others out, taking advantage of them, climbing over them to get ourselves higher? Or do we emanate the character of God who brings rain to both the righteous/obedient and the godless. Is our nature and are our actions such that they bring Life to others and gather humanity? or are we suffocating and pushing people groups out.

You wrote in your little expose that Paul first went “…to the Jews of the diaspora and then, when the Jews rejected it, to the Gentiles.” It is a numerical and statistical fact that there were many more Gentiles who rejected Paul’s message than Jews. But your statement groups people into two exclusive groups: Jews or Gentiles. The Good News, however, was that we—like the Jews—received the honor to all become members of God’s family.

You wrote “…Salvation for Israel depended on the response of individual Jews to this message… .” The descendants of Abraham are under covenant, whether they like it or not. One can convert to Judaism, but still not be a Jew. To become a Jew one needs to accept the terms of the covenant AND be accepted by those already under the covenant. This is why becoming a Jew is so very difficult. Conversion to Judaism is effectively an action one can take individually. Becoming a Jew requires the formal approval of your genuine acceptance of Covenant terms by an authorized Orthodox Rabbinate. And becoming a Jew cannot be undone: Once a Jew always a Jew—even if you would turn your back on Judaism and/or YWYH altogether. History unambiguously evidences the reality that God has a plan with His covenant people. The incomprehensible injustice of the Holocaust—unparalleled in history—preceded the Declaration of Independence of the State of Israel by a mere few years. It is not correct to state that the Salvation for Israel depended on the response of individual Jews to “this” message ( = Gospel message). As a matter of historic fact, that very position has been fuelling anti-Semitism for two millennia, culminating in the evil-of-evils: The Shoah/Holocaust.

You also wrote that “…It was good news that judgment was coming on pagan Rome… . This too is yet another exclusivist characterization of an entire demography. Jesus never used such language. He never singled out “The Roman,” “The Jew,” “The Samaritan.” He smilingly left the focus on the beam in our own eyes. Rome knew very many wonderful people… .

It is so much easier to discuss theology than to align my life with the soft and gently whisper of God to humbly walk with Him, whilst loving and serving all. Theory is important, but any theory—and most certainly any theory about Good News—has to be built around the reality that God does not discriminate. And that reality has been evidenced by both the records in the Old Testament, as well as the Gospels (though I am not so sure about Paul). As Jesus stated: Naaman was healed, and the Sidonian widow was sustained, the good Samaritan honored, and the Roman centurion’s servant was healed.

Now that’s Good News :-)

@Hans Dekkers:

It is not correct to state that the Salvation for Israel depended on the response of individual Jews to “this” message ( = Gospel message).

Hans, it’s a real pleasure to hear from you! Warm greetings to the family.

As a matter of interpretation, I don’t really see what the problem is. An interpretation is not made false by the fact that it later became a source of anti-Semitism. That’s a problem, but it’s not an exegetical problem.

Perhaps I’ve made the point a little too sharply, but it seems to me that Jesus and the apostles put the ball very much in Israel’s court: you can choose, individually, either to remain on a broad road leading to the judgment of AD 70, or you can take the narrow path leading to life—to the surviving of a viable people of God. Peter urged the people of Jerusalem to call upon the name of the Lord or face the devastation that would inevitably come upon a “crooked generation” (Acts 2:21, 37-40). Paul believed that the Jews were “vessels of wrath prepared for destruction”; they were being broken off the olive tree that grew from the rich root of the patriarchs (Rom. 9:22; 11:16-24).

The point I would emphasize is that this is an argument relevant for the first century. Judgment and salvation have to do with the impact of the Jewish War against Rome. From the perspective of the New Testament that was, I think, a “final” judgment on Israel according to the Law. How we write the later history of the Jews—anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, the establishment of the State of Israel, the wars against the Arabs, etc.—into the story is another matter, beyond the purview of the New Testament.

I didn’t accuse Jesus of pronouncing judgment on pagan Rome. I don’t think he does. But Paul certainly does, Revelation certainly does. I think that in Romans 2 Paul acknowledges the fact that there were ordinary righteous Gentiles who would escape the wrath of God against the Greek—in fact, they would put the Jews to shame on this day of judgment.

As Jesus stated: Naaman was healed, and the Sidonian widow was sustained, the good Samaritan honored, and the Roman centurion’s servant was healed.

Hans, this argument that God does not discriminate is unsustainable. For a start, these examples all explicitly highlight the fact that the Jews had fallen short of the glory of God—that God was actively discriminating against them. The point is not that God does not discriminate but that, on the one hand, he is an impartial judge, and on the other, he accepts all who call on the name of the Lord, regardless of gender, status, or ethnicity.

It seems to me that hospitality is a much more appropriate paradigm for the response of the people of God to “the other” than inclusion.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew, warm greetings to your loved ones too :) We’re all growing up.

It seems to me that hospitality is a much more appropriate paradigm for the response of the people of God to “the other” than inclusion.

I like that, but it still leaves the door open to the notion that…” we may be hospitable to you, but that doesn’t mean you’re in!”

What fascinates me, also in your reply to my comments, is that we so very quickly concern ourselves with God’s responsibilities. Who God includes or not is not our responsibility: It is His responsibility. One of the realities I learn more and more as I gain more and more grey hair, is that I basically know so very little of the people around me, that any notion of judging discernment is bound to be incomplete. We have to rid ourselves altogether of thinking in terms of in-crowd and out-crowd.

What does it really mean to call upon the name of the Lord, as you quoted Peter. Is this a magic wand formula? How do we reconcile this with Jesus’ words concerning those who cry out Lord, Lord, and yet He doesn’t acknowledge them? even stating: Away from me you evil doers!

What if we simply look at the entire perspective from Genesis to Revelation and discover the Creator in the logical and justified need to (a) have relationship with his Creation, and (b) see His Creation interact in a life-giving, chesed/favor/grace sort of way to one another (as every father would love to see)?

The entire emphasis from my perspective and understanding is precisely that. This perspective lies the responsibility wholly in our own laps. It is each individual’s responsibility to respect and acknowledge, and each individual’s responsibility to acknowledge and be hospitable (to use your preferred term) to others.

It cannot be that this is dependent on one’s theology. And if it would be, then what would be more important: the correct theology or the actual actions expressing those two main areas of responsibility? Surely, blessing and curse will not come our way on the basis of the results of a theology exam.

I quote myself…

As Jesus stated: Naaman was healed, and the Sidonian widow was sustained, the good Samaritan honored, and the Roman centurion’s servant was healed.

This is my point: How can you possibly reconcile God’s demonstrated sovereign justice with quote/unquote human versions of theology. Are my Hindi IT colleagues in Bangalore doomed if their version of theology differs from mine? What if my theology is 90% correct, and theirs only 10% correct, but… their actions respecting and acknowledging “Higher Power” as well as their actions of love and care and respect to others exceed both that of mine? Will my theology advantage get me in? and they out? What if they are actually atheists, but do pause to listen to the Lark in the Spring sky, impressed by “Mother Nature” and then move on to help an incontinent old lady to make it through her day of dementia. Will their theological shortfall do them under, where I may be a religious bigot albeit with sound theology (putting it a bit harshly)?

Frankly, I don’t think any attempt to interpret and relay the Good News along those ways is ever going to “get it right.” We have been bombarded with the concept of God’s love for me (me, I, myself, moi) that we cannot even start to fathom how great his love really is… .

I know your hospitality from experience, Andrew, and it taught me the art :-) so don’t take my words personal. I am just obsessed with my planks… and let God be God.

And don’t hear me wrong… We are all stewards of “what we understand” but I have witnessed evangelical professionals (full time outreachers, or whatever you want to call them) sitting in a cab trying the “convert” the taxi driver… and in fact demonstrating zero interest in the man. It was all about the pushing of their own theology into the throat of the taxi driver. Over time I increasingly question that logic.

The obey is better than sacrifice.

How to wrap that into theology? Good question :-) but I’m no longer there… I simply strive to live the Shema, embrace the conclusion of the Kohelet, and agree with the lyrics of Bob Dylan: No matter who we are, the bottom line is “who are we serving? It may be the devil, or it may be the Lord, but we’re all serving the one or the other. We all give more life and breath to others, or rob it from them to the advancement of ourselves. The proper interpretation of the Good News ultimately needs to fall in line with such realities. But most interpretations come at the expense of at least some of my neighbors, whom—God adamantly instructs me from Genesis to Relevation—I am to love.

Shabbat Shalom

@Hans Dekkers:

I like that, but it still leaves the door open to the notion that… “we may be hospitable to you, but that doesn’t mean you’re in!”

My view there is that we make too much of being in. It seems to me that the whole biblical story is predicated the choice of a priestly people from amongst other peoples to be loyal to the creator God. I don’t think that the New Testament changes that. Gentiles are no longer excluded and the people now relates to the creator through Christ, but the basic arrangement is the same. A loyal people bears consistent witness to the reality of the true and living God, come what may. It’s a vocation, a responsibility. Lots of people in the world don’t want to be included. They don’t buy the premise. They don’t want the responsibility.

What does it really mean to call upon the name of the Lord, as you quoted Peter. Is this a magic wand formula? How do we reconcile this with Jesus’ words concerning those who cry out Lord, Lord, and yet He doesn’t acknowledge them? even stating: Away from me you evil doers!

Wasn’t the point simply that they were hypocrites? Some people say “I love you” and mean it. Some people say it and don’t.

What if we simply look at the entire perspective from Genesis to Revelation and discover the Creator in the logical and justified need to (a) have relationship with his Creation, and (b) see His Creation interact in a life-giving, chesed/favor/grace sort of way to one another (as every father would love to see)?

But is this how the Bible presents things? There’s a great deal about God’s desire for a relationship with his people but very little to suggest that he is urgently seeking a relationship with creation as a whole or with humanity as a whole. The position that you are taking may be excellent from a modern point of view—indeed, that seems to be how you are putting it:

The entire emphasis from my perspective and understanding is precisely that. This perspective lies the responsibility wholly in our own laps. It is each individual’s responsibility to respect and acknowledge, and each individual’s responsibility to acknowledge and be hospitable (to use your preferred term) to others.

But that modern perspective is not necessarily the perspective of Isaiah or Jesus or Peter or Paul. One of the reasons why I am advocating a narrative-historical hermeneutic is that it pushes us to let the New Testament speak on its own terms, in its own context, with its own restricted historical horizons. So the question is not “What does it mean to call on the name of the Lord?” but “What was Peter saying to first century Israel when he quoted that passage from Joel?” Otherwise we just end up making things mean what we want them to mean.

As for your Hindu friend in Bangalore, I would say that God will judge all people impartially at a final judgment according to what they have done. But I believe he will be gracious towards those who, through their lives and witness, have faithfully served as priests and prophets the God who raised his Son Jesus from the dead.

@Andrew Perriman:

You certainly started a lively discussion, Andrew, with very many viewpoints represented. That too indicates what you referred to in your last reply to me: A modern day, in which everybody does and things and holds on to what is right in their own eyes :-)

If I zoom out and away from the discussion per se, I observe a trend which causes “The Church” as we have known it to be all but irrelevant. Billboards with slogans on sidewalks outside a slowly degenerating building in need of paints, where some X number of people, with hardly any children, gather to listen to a monologue and here some songs. And yet, society as a whole needs to hear “their” judgment and opinion on how godless the world has become.

Here in my region there is a maxim: Are you part of the problem? Part of the solution? If not: Stay out of it.

“The Church” (horribly generalization, I’m sorry) is a sideline critic, with no relevant bearing on solutions. And why has this come to be? That is obviously a huge question which has a lot to do with the interpretation of Good News. A self-focussed obsession with a judgmental perspective to all those who think differently.

I spoke once to represent the Judaism position on a theological interfaith symposium. My church leadership did not even dare to consider attending out of fear of “the other” with their godless doctrines.

This is not a venting of frustration, but an urge to help find genuine God-honoring relevance of the Good News. Historically correct relevance, as you appropriately put it, Andrew. Not taking words of the past and twist it to our own ears, but ridding ourselves of two millenia of exclusivist interpretation and trying to humbly hear what God really said. And to “hear” that in the lines of Scripture, the first thing to rid ourselves of is self, me, I, and start thinking like us, we, together.

Thanks for the share, Andrew. Greetings to all.

@Hans Dekkers:

To pull it totally out of perspective, Andrew, or rather into it… Watch this…

Windmills of your mind (Thomas Crown Affair) is one of my most favorite popular songs. Noel Harrison sang the original English version, and String redid it for the new movie version, but today I discovered Eva Mendes. Brilliantly performed. http://youtu.be/WJ5QEXzPpE0

As James writes: Every good and perfect gift comes from above, from the Father. I have absolutely no idea about the lives of this song writer, the composer, nor of Mrs. Mendes, but… this song cuts through my heart as few others do. Somehow, it needs to “fit” in the Good News, for surely it is God-breathed.

Have a wonderful weekend, Andrew. Until we meet again (hopefully a bit earlier than very many years :-)

Quite a large focus here as elsewhere in your writings Andrew on the gospel as having its narrative impact through judgment on Israel’s/God’s people’s enemies (thereby preserving God’s people).

I think the supposed narrative/personal salvation divide is resolved when the kingdom of God (as described mainly in the gospels) is defined not simply as an act (acts) of judgment, but as the history-changing significance of God becoming King — through His return to the temple (now God’s people) and through esablishing a co-regent on earth (Jesus). Heaven comes to earth.

The gospel today is not simply about ‘personal salvation’ as narrowly defined, but as the call to become subjects of the King (Jesus), and conform to his agenda (sermon on the mount, and the operation of the Spirit for which there is no parallel either before or since). By doing so, we conform to God’s plans for His creation — in this world. Heaven and earth becoming reconciled and reunited.

The gospels give us a window into what that looks like, and can still look like today, both in principle and as a literal reality.

The gospels are “the gospel” — the good news of what it looks like when God becomes King — then and now.

I’ve just given away my copy of The Jesus Creed (that’s as far as I could get with McKnight). I could never get into it. Along with 75% of my book collection, now sitting in eight boxes on the dining room floor. Decided it’s time to move on!

@peter wilkinson:

Where—or how—in the Gospels is the kingdom of God described as “the history-changing significance of God becoming King” apart from the coming judgment on Israel?

Does God become king or act sovereignly, which is how I put it:

The good news was that God was about to act sovereignly as king, he was about to intervene decisively in the history of Israel.

Jesus presumably asserts a claim to be Israel’s king when he rides into Jerusalem, but when he goes to the temple, he enacts judgment. Does Jesus at any point speak of or enact the return of the glory of God to the temple—in the manner of Ezekiel’s vision?

In this connection, Jesus quotes Malachi 3:1 with reference to the role of John the Baptist (Matt. 11:10), but Malachi 3:4 speaks of God coming in judgment to the temple, to refine the priesthood, so that the “offering of Judah and Jerusalem will be pleasing to the Lord”.

It makes more sense, I would have thought, to speak of God becoming king vis-à-vis the nations, but that takes us outside the Gospels.

And why do you say “establishing a co-regent on earth (Jesus)”? Jesus became a co-regent in heaven. His rule is no more “on earth” than YHWH’s rule was.

I agree, though, obviously, that there are two sides to the coming of the kingdom of God—judgment and restoration.

Thank you for expanding the view of the gospel. All I ever hear is a very narrow view of gospel=Jesus died for you to take away your sin and give you eternal life in heaven. (The alternative as to going to hell is sometimes mentioned…)

What do you mean — unpack if you will..your comment above “paint alternative, unexpected futures;”…? Thanks

@Scott:

I had 1 Thessalonians 1:9-10 in mind in the first place:

For they themselves report concerning us the kind of reception we had among you, and how you turned to God from idols to serve the living and true God, and to wait for his Son from heaven, whom he raised from the dead, Jesus who delivers us from the wrath to come. (1 Thess. 1:9–10)

The Thessalonians had not been converted only to a new relationship with God. They had been converted to a new view of the future—in this case, a future in which the God of Israel would judge and overturn the dominant pagan system. See also The good news of a different future.

Our future is not their future, but it seems to me that a narrative theology must retain a strong “eschatological” dimension—simply because narratives don’t stop. This will remain true at an individual level: a new relationship with God will inevitably result in a transformed individual future. But more importantly, I think we need to learn how to speak prophetically and credibly about larger futures, having to do with the place of the people of God in the world. And beyond that, I think it is right that we speak about the ultimate renewal of all things and defeat of all evil as a supreme expression of confidence in the Creator.

I’d just like to pass on another way to help spread the gospel and it’s simply this:-

Include a link to an online gospel tract (e.g. www.freecartoontract.com/animation) as part of your email signature.

An email signature is a piece of customizable HTML or text that most email programs will allow you to add to all your outgoing emails. For example, it commonly contains name and contact details — but it could also (of course) contain a link to a gospel tract.

For example, it might say something like, “p.s. you might like this gospel cartoon …” or “p.s. have you seen this?”.

Recent comments