Richard Worden Wilson has drawn attention to a short piece by Scot McKnight on the relation between Paul’s statement about one God and one Lord in 1 Corinthians 8:6 and the Shema, the great Jewish confession that “The LORD our God (yhwh eloheinu), the LORD (yhwh) is one” (Deut 6:4). McKnight thinks that “one Lord, Jesus Christ” identifies Jesus with YHWH: ‘astoundingly, Paul sees “God” (Elohim) as the Father and he sees “Lord” (YHWH) as Jesus’.

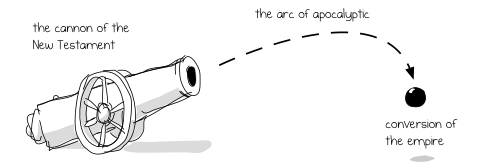

I respectfully disagree with this interpretation. I think it is a mistake to identify the “Lord” who is Jesus in Paul’s statement with YHWH, for reasons which I will set out. But first I want to say again, for the benefit of those who want to banish me into outer darkness, that this is not an argument against the view that Jesus is presented in the New Testament as God. It is an argument for the view that this is not what is meant by the confession that Jesus is Lord. It is the argument that at the heart of the New Testament is the apocalyptic story of how the God of Israel raised his obedient Son from the dead and gave him authority to judge and rule over the nations, a narrative trajectory which I suggest found its historical fulfilment in the conversion of the empire. [pullquote]It is an argument for thinking that this historical ambition is much more important for understanding the New Testament than the assertion of Jesus’ divinity.[/pullquote]

Now for my reasons….

1. The statement “there is no God but one” in 1 Corinthians 8:4 alludes to the Shema and perhaps a couple of other texts: “the LORD (yhwh) is God; there is no other besides him…. the LORD (yhwh) is God in heaven above and on the earth beneath; there is no other” (Deut. 4:35, 39). These texts all include YHWH in the formula, but Paul has dropped “Lord” and states merely that “God” is one. This renders the allusion a little hazy.

2. Paul’s assertion that “for us there is one God, the Father, from whom are all things and for whom we exist” has stronger and more extensive links to Malachi 2:10-11 than to Deuteronomy 6:4 (LXX):

Did not one God create us? Is there not one Father of us all? Why then did each of you forsake his brother, to profane the covenant of our fathers? Judah was forsaken, and an abomination occurred in Israel and in Jerusalem, for Judah profaned the sacred things of the Lord with which he loved and busied himself with foreign gods.

Contextually, this matches Paul’s argument against idolatry rather well: entanglement with foreign gods is potentially, at least, a contradiction of the fundamental Jewish conviction that there is one true creator God. The Shema may still be in the background (note also Deut. 6:14), but the evident relevance of the Malachi passage suggests that Paul’s intention was not so much to reformulate the Shema as to affirm in the language of the prophets—Deutero-Isaiah is also clearly germane—the uniqueness of God the Father who created us.

3. Paul acknowledges that there are “many gods and many lords” in the world which are worshipped or obeyed. The kyrioi could perhaps be the same as the “gods”. They could be deified rulers. In any case, when he says that “for us there is… one Lord, Jesus Christ”, the first point of reference in the flow of Paul’s argument is not to the Shema, which has not been brought clearly into focus, but to the “many lords” acknowledged in the idolatrous pagan world. The meaning of kyrios in this context is very different to the meaning of “LORD” (i.e. YHWH) in Deuteronomy 6:4.

4. To the extent that New Testament thought about the status of Jesus is controlled by Psalm 110:1,1 we have to reckon with a distinction between the “LORD” which is YHWH and the “Lord” which is kyrios:

The LORD says to my Lord: “Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool.”

I noted in a previous post Dunn’s argument that the second part of Paul’s formula is determined by this verse. The one God who is YHWH grants the one Lord (adon, kyrios) who is Jesus the right to rule at his right hand until those who oppose him are subdued. There is, then, a strong case for thinking that this distinction governs the application of texts such as Isaiah 45:22-23 and Joel 2:32 to Jesus.

5. Presumably for the sake of the parallelism Paul adds to the confession about Jesus “through whom are all things and through whom we exist”. The thought owes something to Jewish wisdom traditions (cf. Prov. 8:22-31; Wis. 7:22; 9:9). Creation is “from” God but it is “through” Jesus, and “through whom we exist” suggests an eschatological orientation: it is through Jesus’ faithful obedience that a new creation reality as been brought about. The distinction between “from” and “through” weighs heavily against directly equating Jesus with YHWH in this passage, but the association of Jesus with the “word” and “wisdom” of God certainly points in the direction of Jesus’ unique participation in the creative action of God. Whether action can then be translated into identity, as Bauckham argues, is another matter. If we step back far enough—say two to three hundred years—I think it probably can.

So when Paul says that “for us there is… one Lord, Jesus Christ”, he is not saying that Jesus is the “LORD” in the Shema, that Jesus is YHWH. He is saying that Jesus has been given an authority—or a name—above that of all the other “lords” that hold sway in the Greek-Roman world. He does not have this authority as YHWH. He has received it from YHWH.

- 1See Matt. 22:44; 26:64; Mk. 12:36; Lk. 20:42, 43; Acts 2:34, 35; 1 Cor. 15:25; Eph. 1:20-22; Col. 3:1; Heb. 1:3, 13; 2:8; 8:1; 10:12-13; 12:2; 1 Pet. 3:22.

I take your point, but to over-emphasize it would be to miss the striking effect of what Paul does when he brings the Shema confession into what he says about God, Jesus, and, arguably, YHWH.

The context of 1 Corinthians 8:6 is pagan idolatry, but the striking feature of the passage is first the parallelism of God and Jesus — “from whom/for whom and through whom/through whom are all things … we exist”, besides the differentiation (leaving aside the wisdom argument for a moment).

Then within the Shema confession, Paul goes further, first substituting God for Lord (LXX Kyrios) in the first part, and then, before we’ve had time to reflect on that, he identifies Jesus with Kyrios, the YHWH substitute — LXX Deuteronomy 6:4, in the second part. In other words, while we were wondering what had happened to Kyrios in the first part of the confession, it suddenly reappears in direct identification with Jesus in the next part. This association is inescapable and striking.

I’m not convinced by the ‘wisdom’ argument, which identifies Jesus with ‘wisdom’ in the creation of the world. ‘Wisdom’ in Proverbs (and the Wisdom passage you quote) is a figure of speech, a personification, not a person, or a separate proto-Jesus figure. I therefore question those who see Jesus as representing wisdom in some of the NT passages.

Kyrios as the anti-idolatry or anti-emperor figure is perhaps a secondary association of the word, which is arguable given the context of the passage. But to make this a primary meaning overlooks something even more striking. I think, too, you may be setting up an antithesis (Kyrios as anti-idolatry instead of YHWH), where the sense of the passage is both.

I also think the ‘strong links’ you suggest with Malachi are only strong if you accept the assumptions made in your argument, which deny the more striking effect of the echo of the Shema — in itself, by the way, a dissociation from idolatry.

Your statement: “He (Jesus) does not have this authority as YHWH. He has received it from YHWH” needs more attention, but it suggests something that I dispute, that Jesus was only a delegated agent of YHWH. The contrary is evident from 1 Corinthians 8:6, and no amount of re-interpreting the passage will say anything different — even given your anti-idolatry association and echo of Malachi.

Dunn’s argument, which you cite, that Jesus was granted authority from God in the second part of the passage, has been roundly disputed, to the extent that I don’t think any serious scholar accepts it any more as a valid interpretion of the passage.

@peter wilkinson:

I notice you skirt round the point about Psalm 110:1, which is arguably the most important Old Testament text for understanding the relation between God and the risen Christ in the New Testament.

Bauckham thinks that Wisdom is a hypostasis at least in some texts. And even if it’s only a personification, the echoes are so strong that it’s very difficult to discount some sort of literary-theological influence.

I also think the ‘strong links’ you suggest with Malachi are only strong if you accept the assumptions made in your argument, which deny the more striking effect of the echo of the Shema - in itself, by the way, a dissociation from idolatry.

But the links to Malachi 2 are clearly stronger than the links to the Shema—you also have the reference to father and to creation, which are not found in the Shema. I don’t think any great assumption has to be made here. I think there is ground for questioning the conventional view about the “more striking effect of the echo of the Shema”.

@Andrew Perriman:

I notice you skirt round the point about Psalm 110:1, which is arguably the most important Old Testament text for understanding the relation between God and the risen Christ in the New Testament

I did refer to current opinion which rejects Dunn’s view that 1 Corinthians 8:6b is interpreted by Psalm 110:1.

On the first point you make on Psalm 110:1, you say:

To the extent that New Testament thought about the status of Jesus is controlled by Psalm 110:1,1 we have to reckon with a distinction between the “LORD” which is YHWH and the “Lord” which is kyrios

The distinction you want to make, which sees Kyrios as anti-idolatry/emperor, is tempered by the contrary view which notices and reflects on identical words used in the Psalm to describe ‘Lord’ and ‘my Lord’, rather than different words to clearly distinguish entirely different beings.

Psalm 110:1 is used in the NT to describe Jesus’s post-resurrection exaltation. Whatever that means, I don’t see it being used in the NT to describe primarily an exaltation over idolatry or Rome, with the possibility of 1 Corinthians 6:8 being a disputed exception.

Of 1 Corinthians 8:6 and Malachi 2:10, you say:

But the links to Malachi 2 are clearly stronger than the links to the Shema—you also have the reference to father and to creation, which are not found in the Shema

I think it’s more likely that the emphasis in Malachi on “one father”, “one God” has the Shema as its reference point — in the emphasis on God’s transecendent uniqueness.

Malachi adds Father in the sense of Creator, which 1 Corinthians 8:6 also has, so in that sense it’s an interesting parallel. Yet perhaps even more remarkable is that 1 Coritnhians 8:6 points to Jesus (“by whom are all things, and we by him”) as creator and restorer of creation.

The contextual parallel with idolatry in Malachi is also remarkable — but not to the extent that it excludes a greater role for Jesus in creation and re-creation.

So I should have acknowledged more your highlighting of Malachi 2:10 in interpreting 1 Corinthians 8:6; it certainly looks as if it is there, but I don’t see it making the either/or antithesis (Jesus as anti emperor or divine being but not both) that you propose. I still think the primary echo of the Shema, with Jesus now included, is the primary feature of 1 Corinthians 8:6, for the reasons I set out.

And henceforth let no man trouble me, for I bear in my body the marks of one who travelleth with his wife Annelise to Perranporth for a few days ‘holiday’, wherein there is no internet connectivity, and I haveth not a smartphone.

@peter wilkinson:

The distinction you want to make, which sees Kyrios as anti-idolatry/emperor, is tempered by the contrary view which notices and reflects on identical words used in the Psalm to describe ‘Lord’ and ‘my Lord’, rather than different words to clearly distinguish entirely different beings.

I don’t follow this. YHWH makes the psalmist’s adon sit at his right hand; he instructs him to rule in the midst of his enemies; his people will offer themselves (ie. this adon is Israel’s king); YHWH declares him to be a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek; the adon is at the right hand of God; he will execute judgment among the nations, etc.

I can see that there is a bit of an issue with verse 5: “The Lord on thy right hand smote kings in the day of His anger” (ESV). I’m a bit puzzled here. The Hebrew appears to read adoni (אדני, “my lord”), as in verse 1, which would suggest that verses 5-7 still refer to the king—notice the very human action of verse 7. “In the day of this anger (af)” is not the same as “in the day of his wrath”.

It will wait till you get back.

@Andrew Perriman:

Hi there, Andrew

Vs. 5 of the psalm would not weaken the case. It refers to YHWH, but the text underwent “correction” by the Sopherim. The “correction” was not, however to change the subject from divine to non-divine. Out of reverence for the Name the change was merely from YHWH to ADoNaI (also vocalised as such). The anthropomorphisms in 5-7 were the major issue here.

No such claim can be made, however, re. vs. 1. As soon as I finish my article (which lingers due to various other time-demanding commitments) I will indicate why the modern Evangelical “Masoretic Conspiracy Theory” proves to be the epitome of dogmatic desperation.

Thanks,

@Andrew Perriman:

Your analysis on this is spot on.

It’s is pretty darned simple. God (YHWH) has appointed Jesus (adon) as his representative to rule the earth. That’s the precise and simple formulation in the Psalm.

People who read the writings in antiquity didn’t need PhDs to figure it out.

@Andrew Perriman:

I don’t follow this. YHWH makes the psalmist’s adon sit at his right hand; he instructs him to rule in the midst of his enemies; his people will offer themselves (ie. this adon is Israel’s king); YHWH declares him to be a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek; the adon is at the right hand of God; he will execute judgment among the nations, etc.

What’s not to follow? The conundrum of Psalm 110 is the repetition of Adonai/Kyrie. All that is said of adoni is true of Jesus as divine messiah for Israel.

Jesus himself highlights the conundrum in Matthew 22:41-46, and comes close to suggesting his own divine identity.

This could become another pointless discussion. The interpretation of Psalm 110:1 in the NT depends on your view of Jesus’s exaltation. The whole son of man debate revolves around this issue.

What you haven’t done, apart from looking at all my other points, is look at the issue that in the NT, Psalm 110:1 doesn’t have the imminent destruction of Israel’s enemies as its context.

St Perran/Piran swam to Perranporth from Ireland on a millstone, and converted the pagans. We kept an eye open for the millstone, and noted one or two candidates. In my reverie, I wondered whether this was another hypostasization: St Perran — Perriman. Or even a narrative-historical interpretation of the story. There must be a connection somewhere.

The attempt to distance 1 Corinthians 8:6 from the Shema overlooks the deliberate literary structure and polemical context in which Paul invokes the phrase “one God” and “one Lord.” Paul is not merely drawing on general Old Testament monotheistic affirmations; rather, he is reworking the Shema in a Christian key. The Shema proclaims, “Hear, O Israel: YHWH our God, YHWH is one” (Deut 6:4). In the Greek Septuagint, this becomes “κύριος ὁ θεὸς ἡμῶν κύριος εἷς ἐστιν.” The striking parallel between this and Paul’s formula—“εἷς θεὸς ὁ πατὴρ… καὶ εἷς κύριος Ἰησοῦς Χριστός”—is hardly coincidental. Rather than diverging from the Shema, Paul has bifurcated its core terms (God and Lord) between the Father and the Son, maintaining the strict monotheistic framework while incorporating Jesus into the unique divine identity. As Richard Bauckham and others have persuasively argued, this is not a diminution but a profound reinterpretation of Israel’s monotheism in light of the Christ event.

The suggestion that Paul’s reference to “one God” is more closely tied to Malachi 2:10-11 than to Deuteronomy 6:4 is hermeneutically strained. Malachi’s language of “one God” and “one Father” is certainly compatible with Paul’s theology, but the idea that Paul is primarily drawing from a post-exilic prophetic oracle rather than the foundational Jewish confession of monotheism seems historically implausible. The Shema was recited daily by devout Jews and formed the very heartbeat of Jewish identity. To suppose that Paul, a Pharisee trained in the Torah, would ignore the Shema in favor of a more obscure prophetic allusion, especially in a passage directly addressing idolatry and the uniqueness of the true God, stretches credulity. The polemical force of 1 Corinthians 8 lies precisely in its redefinition of monotheism around Christ, in contrast to pagan polytheism.

Moreover, the attempt to restrict the title “Lord” (κύριος) in 1 Corinthians 8:6 to a mere contrast with pagan “lords” (κύριοι πολλοί) ignores the wider New Testament usage of the term. While it is true that Paul acknowledges many so-called “gods” and “lords” in the pagan world, the application of “one Lord” to Jesus is not simply rhetorical or comparative. Rather, it reflects the highest possible designation available in Greek for Israel’s God—κύριος, the Septuagint’s rendering of the divine name YHWH. Paul’s choice of terminology is deliberate and profound. If Paul had wished to indicate a merely exalted but non-divine Christ, alternative Greek terms were readily available: despotes (master), hegemon (leader), or even the generic archon (ruler). His selection of kyrios—in a confessional context linked with theos—signals something far greater. The earliest Christian communities, steeped in the Septuagint, would not have missed this identification.

The citation of Psalm 110:1 and the attempt to distinguish between “YHWH” and “my Lord” (adoni) to support a subordinationist reading of Jesus’ lordship also falters upon closer inspection. Psalm 110:1 is one of the most cited texts in the New Testament precisely because it highlights the paradoxical exaltation of the Messiah to a position at God’s right hand—a position of divine prerogative. The word adoni (my lord) in the Hebrew text may lack the Tetragrammaton’s force, but the New Testament consistently reads this passage through the lens of kyrios in the Greek, further blurring the distinction between the two titles. Importantly, the New Testament application of Psalm 110 to Jesus is not framed as the elevation of a mere creature, but as the enthronement of the one who shares in God’s identity and authority. Jesus is not merely given the name “Lord” in the sense of status, but participates in the divine name itself (cf. Phil 2:9-11), a truth underscored by the fact that the very worship (προσκυνέω) and service (λατρεύω) due to YHWH are directed to Jesus (cf. Rev 5:13-14; Rev 22:3).

The final point concerning the “from/through” distinction in creation likewise fails to support a non-divine Christology. The fact that “all things are from the Father” and “through the Son” does not suggest an ontological hierarchy or metaphysical separation. Rather, it aligns precisely with the doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son and the traditional opera Trinitatis ad extra, which affirms that the external works of the Trinity are undivided but expressed with proper order. The Father is the source (ek), the Son the agent (dia), and the Spirit the perfecting presence (en). Paul’s language mirrors this structure without undermining the Son’s divinity. To cite Wisdom literature (e.g., Proverbs 8 or Wisdom of Solomon 9) without recognizing the early Christian reapplication of those themes to the pre-existent, divine Logos (as in John 1:1-3, Col 1:15-17, and Hebrews 1:2-3) misses the trajectory of Second Temple Jewish thought as it coalesces in the figure of Christ.

Thus, far from denying or minimizing Christ’s divine identity, 1 Corinthians 8:6 reaffirms and deepens it. The apostolic witness does not consist of isolated proof texts but of a coherent, Spirit-guided re-reading of Israel’s Scriptures in light of the death and resurrection of Jesus. Within that framework, the identification of Jesus with the “Lord” of the Shema is not merely theological speculation but the confession of the earliest Church. The passage’s structure, terminology, and liturgical context all converge to present Jesus not merely as an exalted agent, but as the eternal Son who shares in the divine identity. To separate “confessing Jesus as Lord” from recognizing His divine nature is to divide what Scripture and Tradition have always held together.

Recent comments