By comparison with “hell”, which in its traditional sense is not a biblical idea, “heaven” ought to be a fairly straightforward theological concept to explain. Surely heaven is simply what belief in Jesus is ultimately all about? It’s where we go when we die. It’s what makes sitting through—or preaching—all those tedious sermons worth while. The party at the end of the cosmos. The thumping rock and roll worship session in the clouds around the throne of God for ever and ever. The marriage feast that will make the impending Royal Wedding celebrations—there will be a reception, surely?—look like a bunch of scruffy winos picking over the congealed remains from a discarded pizza box.

Unfortunately, our popular beliefs about heaven are almost as misconceived as the belief that there is a place called “hell”, deep in the bowels of the cosmos, where the wicked—by “wicked” is often meant “those not chosen”—will be tormented for eternity. Heaven certainly exists, but it is opposed in scripture not to a metaphysical hell (as alternative final destinies), but to earth, in recognition of the fractured structure of creation. The fundamental problem addressed all the way through the biblical metanarrative is not: How are people to get to heaven? but: How is God to live in the midst of his creation?

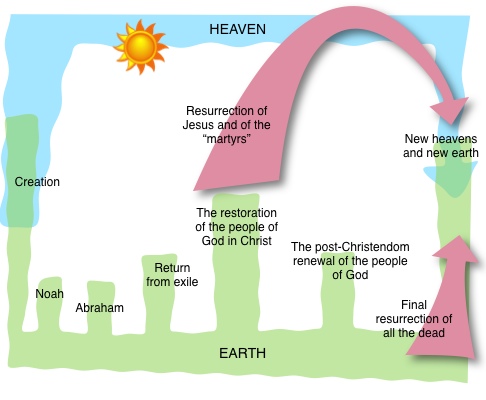

So paradoxically we must begin on earth. What I think we need to highlight, first, is a series of moments (the green bars in the diagram) when God brings about “new creation” within the framework of the old creation: Noah’s family are the seed of a new creation following the destruction of the flood; Abraham is called to be the progenitor of a new humanity in microcosm; Isaiah pictures the return from exile as a new creation; in a more radical way the people of God are made new creation in Christ through the re-creative power of the Spirit of God; and many people today are instinctively reaching for “new creation” language in order to describe the renewal of the church after the collapse of Western Christendom. The people of God are always a sign, by grace, of the Creator God who makes all things new.

On the outer edge of the New Testament’s prophetic imagination this divine drive to re-create gives rise to a vision of a transcendent “new heaven and new earth”, which will constitute the final victory of the Creator God over the powers of evil that had devastated his good creation. Significantly, in John’s visionary narrative the movement is downwards: the holy city, the new Jerusalem, is seen “coming down out of heaven from God”; and a loud voice from the throne proclaims, “Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God” (Rev. 21:2-3). This is the final answer to the recurring question: How is God to live in the midst of his creation?

Prior to this consummation it is only under exceptional circumstances that God becomes present on earth—in a burning bush, in fire and smoke on Mount Sinai, painstakingly sequestered in the Holy of Holies, in Christ, or since Pentecost in the temple of his people, through the Spirit.

It is also rather exceptional for people to go to heaven. Enoch and Elijah were transported directly to heaven while alive (Gen. 5:24; 2 Kgs. 2;11; cf. Heb. 11:5), which is remarkable by anyone’s standards. Jesus ascended into heaven after his resurrection and now sits at the right hand of the Father, having received kingdom and power and glory as a result of his faithful obedience to the point of death.

A trinitarian theology rather obscures the oddity of this christological development. Once Jesus has been assimilated into the fuzzy metaphysical community of the godhead, it is not merely his earthly existence that tends to fall away; his new humanity also gets forgotten about. But as firstfruits from the dead, the resurrected Jesus is a sign of a final new creation. He is only temporarily in heaven. The ultimate is still to come.

But what about the rest of us? Here’s where I take an admittedly unconventional turn. Why does John differentiate between a limited first resurrection of those who “had been beheaded for the testimony of Jesus and for the word of God” (Rev. 20:4-5) and a comprehensive second resurrection of all the dead for judgment after the dissolution of the old order of things (Rev. 20:11-13)? That first resurrection, moreover, appears to follow on directly from the defeat of the “beast” of an idolatrous Roman imperialism (Rev. 19:11-21). Those who are raised—those who had not worshipped the beast—then “reigned with Christ for a thousand years”. In other words, they went to heaven.

We could dismiss this as so much imponderable apocalyptic detail, but it seems to me that John is asserting something of crucial significance for the early persecuted churches here—that those who share in Christ’s sufferings, as they confront his enemies, will share in his resurrection and reign.

This is consistent with the origins of the personal resurrection motif in Jewish martyrdom theology (cf. 2 Macc. 7:9, 14). It is also consistent with Paul’s argument that the churches have been called to participate in the story of Jesus’ death and resurrection—not merely symbolically through baptism but practically and literally, through the sacrifice of their lives. When Paul expresses a desire to “depart and be with Christ”, it is in the context of his expressed desire that “I may know him and the power of his resurrection, and may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, that by any means possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead” (Phil. 1:21; 3:10-11). I have also argued that Jesus’ promise to the man being executed next to him, that he will be with him that day “in paradise”, also has its origins in a martyrdom theology.

So what it comes down to, I think, is this. 1) Heaven is not the ultimate destination. In the end, there will be a new heaven and a new earth; and the dwelling of God will be in the midst of things. 2) Jesus has been raised and vindicated and reigns at the right hand of God. 3) The early community that was “conformed to the image of his Son” (Rom. 8:29) through suffering and death has also been raised, vindicated, given kingdom, and reigns with Jesus at the right hand of God. Heaven comes at the end of a particular Christlike journey, which fortunately not all Christians get the chance to walk. 4) According to John, the “rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were ended” (Rev. 20:5). I have suggested elsewhere that this may refer not to the “rest of humanity” but to the dead who opposed the God of Israel during the eschatological crisis. This would mean that all except Jesus and the martyrs will be raised after the earth and sky have fled away. Including believers. We die. We are dead. We are raised at a final judgment. And if our names are not written in the Book of Life, we are thrown into the lake of fire, which is the second death, a second destruction (Rev. 20:11-15). The end.

For once, I agree with most of what you say here Andrew. However, I don’t think there is much, if any, evidence for a ‘proto-resurrection’ of the martyrs. Participation in Christ’s death, burial and resurrection is not simply a call to martyrdom, or even suffering. It’s a call to new life for all believers in all times. It’s how we live as believers in Christ now.

There is substantial biblical evidence for an ‘intermediate state’, as I’ve argued here , which to all practical intents and purposes is heaven for believers in Jesus until the new heaven and new earth. Our conscious experience of union with Christ is unbroken.

@peter wilkinson:

So when John speaks of a first resurrection of those who were beheaded “for the testimony of Jesus and for the word of God”, who come to life and reign with Jesus, a resurrection, moreover, which excludes the “rest of the dead”, that is not evidence for a “proto-resurrection” of the martyrs? “Proto” means “first”, right? “Martyrs” means people who are killed because of their testimony or faith? “Resurrection” means “resurrection”? Two plus two equals four?

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

Do you see this “proto-resurrection” of the martyrs as bodily, in the same manner as Jesus’ ascension to heaven?

It seems to me that this view would need to be confirmed by the missing bodies of the martyrs, unless I’m just misunderstanding you. And would this apply to post-Roman Paganism martyrs; you know, modern missionaries who have been killed, etc?

@Daniel:

Daniel, resurrection is always in principle bodily, but whether this means that we should expect the bodies of the martyrs of the martyrs to have gone awol depends on whether this “proto-resurrection” was like Jesus’ resurrection or like the final resurrection. Presumably at the final resurrection there will be no need for the original earthly body to be raised directly—most bodies will have long been consumed by worms or fire. The martyrs would also have been dead for some time by the time of the judgment of the pagan world and the vindication of the suffering church. In that respect, Jesus’ resurrection was exceptional because it occurred only a couple of days after his death. Though whether questions such as this went through the minds of the early believers is another matter.

I am inclined to say that post-eschatological martyrs—the modern missionaries who have been killed, et al.—fall outside the New Testament storyline. I have no doubt that they will be vindicated and rewarded for their faithfulness, but the New Testament does not address that question. It is the clash with imperial paganism that dominates the outlook.

@Andrew Perriman:

Daniel’s post just drew my attention to this thread again. Two plus two equals four?

There are at least three groups of people in view in Revelation 20:4

- those seated on thrones

- the beheaded martyrs

- those who had not worshipped the beast - ie all the faithful believers who were not beheaded for their faith. Each group is distinguished by the introductory kai.

All members of the three groups “lived and reigned with Christ for 1000 years ,” where the verb “lived” is not “lived again” or “rose from the dead”. The 1000 years is a metaphor of time and triumph, encompassing all the faithful - alive and dead.

In Revelation 20:5, “The rest of the dead” (in other words every non-believer of all kinds who dies in unbelief) did not “live again” - now the verb adds the prefix “again”, because these are exclusively the dead - “until the 1000 years were finished”.

“Resurrection” in verse 5 is to be taken in its secondary sense as the triumph which believers already share with the risen, ascended Christ, as described in John 5:24-29, Ephesians 2:5, Colossians 3:1. This is why it is described as “the first, protos, resurrection, the resurrection being a continuum with two stages, the culmination being physical - new bodies.

This interpretation avoids introducing the the novelty of a distinct resurrection of the beheaded martyrs which is to be found nowhere else in the NT.

@peter wilkinson:

It was helpful to have to look at this more closely. Tried to answer the critique here.

Recent comments