I’ve been away for a week. I was at the Christian Associates European staff conference in the charming town of Tapolca in Hungary. I’m writing this on the plane back to Dubai. Basra is somewhere below us.

The theme for the week—”Walking with Giants”—was taken from Hebrews 11. It makes the whole “faith” business sound a little too easy. What came across, as we reflected on the work of church-planting in Europe in the light of this familiar passage, was just how hard, how uncomfortable, the practice of faith can be. What I took away theologically, however, was the thought that Hebrews, from its rather limited perspective, lends strong support to my narrative-historical reading of the New Testament—not least with regard to the significance of Jesus’ death.

The Letter to the Hebrews is addressed to a Jewish-Christian community that has endured severe persecution and is likely to face worse in the future. They have suffered public abuse, imprisonment, and the confiscation of their property (10:32-34). In their struggle against aggressive Judaism (probably) they have “not yet resisted to the point of shedding your blood”—they have not yet suffered to the extent that Jesus suffered (12:3-4). But the argument of the Letter as a whole suggests that it is only a matter of time before this happens. So the writer pulls all the theological stops out in urging them not to give up but to persevere in order to arrive at the place of rest that lies beyond hardship and suffering (cf. 4:1, 11).

Against this background, a statement that might normally be interpreted within the frame of a standard evangelical soteriology takes on a rather different complexion.

But we see him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone. (Heb. 2:9)

Jesus has been “crowned with glory and honour” because he suffered and died—because he “tasted death for everyone” (2:9). At least part of the purpose behind this was to bring “many sons to glory”. These many sons are those whom he is not ashamed to call “brothers” (2:11). They are also the “children God has given me” (2:13), which is a quotation from Isaiah 8:18:

Behold, I and the children whom the LORD has given me are signs and portents in Israel from the LORD of hosts, who dwells on Mount Zion.

This leads me to think that Jesus’ “brothers”, in this argumentative context, are not simply “Christians”. They are specifically Jewish believers who will sooner or later have to suffer to the same degree that Jesus suffered. With Jesus, they are “signs and portents” to Israel of coming judgment (cf. Is. 8:11-15). But through this suffering they will also be brought to glory.

Jesus’ “brothers” are those for whom he tasted death. Through death he has defeated the one who has the power of death, namely the devil, and delivered “all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery” (Heb. 2:14-15). They have been liberated to pursue the difficult and narrow way of salvation for Israel (cf. Matt. 7:13-14) because there is no longer any reason to fear death. They have seen Jesus “crowned with glory and honour”. They know that if it eventually comes to the shedding of their blood, they too will be brought to glory.

In The Future of the People of God I have argued that Paul develops basically the same martyrology in Romans 8:29 when he writes that those who suffer with Christ are conformed to the image of God’s Son “in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers”. It is only if they suffer with Jesus that they will be glorified with Jesus (Rom. 8:17). The difference is that Paul is writing to the predominantly Gentile church in Rome: Gentiles have been incorporated into prophetic communities that are signs and portents not to Israel only but also to the Greek-Roman world. But this part of the story lies outside the scope of Hebrews.

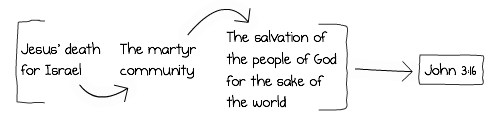

But how does this argument work as part of a general soteriology? What I suggest is that the saving significance of Jesus’ death is mediated to the world precisely through the story of the suffering of the early martyr church.

Jesus’ death in the first place is an act of propitiation or atonement for the sins of Israel. But historically this death only initiates a prophetic movement from within Israel that must pursue the same path of self-sacrifice and at least potential martyrdom. Jesus’ disciples must deny themselves and take up their own crosses if they wish to follow him (cf. Mk. 8:34-35).

In various ways, the assurance is given to the martyr community—the community of the Son of man—that they will be vindicated, raised with Jesus, glorified; they will come to a final place of rest. But the more important outcome of their very difficult faithfulness will be the renewal and reconstitution of the people of God as a global community of new creation.

This historical narrative may certainly be compressed to the dimensions of John’s tight formula: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life” (Jn. 3:16). But this is not “lossless” compression. Right now I think that our shrunken evangelicalism is inadequate. We have to learn how to retell the New Testament story in its full historical complexity.

A couple of thoughts on this, Andrew. In Hebrews, Jesus is presented both as example to follow in his suffering (Hebrews 12:2-4), and as atoning sacrifice and inaugurator of the new covenant in our hearts (Hebrews 9:12-15; 10:1-22). There is a greater emphasis on the latter than the former in Hebrews, though from your perspective, it is still arguable that this is what God did for Israel historically, rather than for humanity universally.

So how is it that Hebrews, along with most of the New Testament and Jesus's actions in particular, has been interpreted as applicable to humanity generally, rather than a story in history which facilitated benefits to humanity, but not directly?

First, because that is how humanity has experienced it, that by believing in Jesus, and in his death as atonement for sins in particular, it is our sins he died for, and by his resurrection and ascension, new life through the Spirit is received from him.

Second, because the wider story at work in the background of the scriptures bears this interpretation out - that Jesus came to bring the story of creation, fall, redemption and new creation to its climax. The passover meal he celebrated with his disciples before his crucifixion enacted the fulfilment of the Exodus as a story in search of a conclusion - in himself. The Exodus was a story within a story - the story of Abraham, with the Exodus as a springboard to entry into Canaan - Genesis 15.

Looking back from Genesis 15, The story of Abraham was couched within a story of creation, fall and universal sin - Genesis 1-11. Looking forward, the entry into Canaan was a springboard for God's universal intentions achieved through Jesus, Abraham's seed, and seed as all those who believed in Jesus.

Much of Hebrews is describing the fulfilment of the OT sacrificial system in Jesus, just as the passover meal he took with his disciples was an enactment of that fulfilment. The difference of emphasis that a narrative interpretation brings to Hebrews is that instead of seeing Hebrews as an invitation to complex typological interpretation of the OT temple and sacrificial system, we can see it as a fulfiment of a story which was winding its way to a conclusion, not, as expected, in the nation of Israel, but in a representative of that nation, through whom the nation's destiny, to bring blessing to the world, would be fulfilled.

I know that discretion should be the better part of valour with these posts, but here I go again putting my head into the lion's den (or something).

@peter wilkinson:

Peter, thanks. I broadly agree with this—and it is a fair point, in particular, that European Christianity successfully obliterated the distinctive Jewishness of the New Testament and made the story of Jesus’ death work universally. The history of the reception of the text is not necessarily a reliable guide for interpretation, but it has to be taken into account nevertheless.

A couple of quibbles though…

…as atoning sacrifice and inaugurator of the new covenant in our hearts…

There is no reference to “our hearts” in the text. As you note, I think that the writer speaks as a Jew to Jews: it is Israel that is redeemed by Jesus’ atoning death, it is the “evil conscience” of rebellious and disobedient Israel that has been purified “from dead works to serve the living God”, it is Israel that enters into a new covenant, etc. Whether it is appropriate to transfer this language to Gentiles or to the rest of humanity is another question, but I think that good exegesis now requires that we preserve the distinctions, reinforce the dykes, mend the conceptual fences—and let the narrative work itself out on its own terms.

I don’t think that the wider story should be characterized as Jesus bringing the “story of creation, fall, redemption and new creation to its climax”. That way of putting it excludes the historical, covenant people of God. I would also take issue with your description of Jesus as a “representative of that nation, through whom the nation’s destiny, to bring blessing to the world, would be fulfilled”.

God’s response to the corruption of human society in Genesis 1-11 was not to redeem what had been corrupted but to call into existence, out of nothing, a new creation. Jesus redeemed this new creation from the condemnation of the Law, which led to its radical transformation, but I think that the basic pattern remains intact: it is a story not of redemption in the first place, but of the corporate, embodied, historically determined witness of God’s people to the goodness and rightness of the creator. Jesus does not displace the calling of a people in Israel: he dies for the sake of the future of that corporate vocation.

@Andrew Perriman:

Briefly, we're not quite on the same page Andrew. My argument is that European, and world Christianity, did not get it wrong. Rather, the message of Hebrews is as applicable to non-Jews as to Jews, because the story it was bringing to completion was not simply Israel's story alone. There was a wider story within which Israel's story was contained: the Exodus within the Abraham story, the Abraham within the creation and fall story.

Far from excluding the historic, covenant people of God by bringing that story to a climax, Jesus includes them by fulfilling the story on their behalf, just as he does for us. The Exodus fulfilment at the passover meal and crucifixion emphasises the inclusion.

Jesus does bring about a long awaited redemption of creation in himself. It is done so through his own resurrection, but that resurrection rested on his own bearing of sin, representatively, and subsequently believing Israel's and the Gentiles' faith in him, and resurrection; a new creation beginning in each of them through faith and Spirit reception - not ex nihilo.

@peter wilkinson:

Briefly, we’re not quite on the same page Andrew. My argument is that European, and world Christianity, did not get it wrong.

I understand that. I was being a little ironic. A bad habit of mine. But my argument is not that European Christendom got it “wrong” so much as that the European adaptation of the Jewish story has only contingent historical validity.

I still think, though, that there is a difference between Jesus’ death redeeming the people of God (and the subsequent inclusion of others in that redeemed people) and the idea which you are suggesting that Jesus’ resurrection redeems creation. Creation is not redeemed—it remains as sinful and rebellious as ever. Jesus’ death, as I have said elsewhere, was an ontological novelty. It prefigures not a final redemption of creation but a final new creation.

We now see people redeemed insofar as they become part of God’s people, but the New Testament perspective is much more bound up with the particular history of Israel.

The “out of nothing” point had reference to Abraham: God created a new people out of nothing, which is what Paul says in Romans 4:17.

@Andrew Perriman:

I thought I had a corner on irony - how could I have missed it?

I wonder at some of the things you say though. Jesus's death not only prefigures a new creation, it was (the start of) the new creation. Redemption is for inclusion within that new creation. This is how the creation-fall/Abraham/Exodus story (all one unfolding story) was brought to completion through Jesus, in himself.

Redemption and new creation are inseparably connected. God calls things that are not (offspring for Abraham, and in this case the completion of the story), as though they are - Romans 4:17. The dead are 'called' to new life when they do not have new life, 'call' being everywhere used by Paul of conversion - when a person comes to faith in Jesus, through whom these things are made possible.

@peter wilkinson:

Jesus’s death not only prefigures a new creation, it was (the start of) the new creation.

Quite right. That’s what I meant by “ontological novelty”. But Jesus’ resurrection also anticipates something, and what it anticipates is not the final redemption of creation but the final remaking of creation. It seems to me that redemption from the old order of things is something that happens, in principle, in the course of history, not at the end of it. But I agree that what is redeemed becomes part of a new creation people.

Andrew, I agree that the original message was one of Jews to Jews, and the story has to be read that way. But I'm puzzled at how the persecutiom of the early church would cause god to judge "jews." History tells us of cruel persecutions of the Romans, starting with (maybe) Claudius and certainly Nero. Why would god react to that by killing Jews and not the Roman persecutors? What did the Jews of that period do wrong to deserve such awful fate?

Peter, I agree that the passages have taken on a broader meaning. However, I don't think it is right to say that the original message was tied to people believing that Jesus died for their sins. Read the sermons in Acts. That construct is not used once in any evangelism. It wasn't until after Jerusalem was destroyed that the message was turned from an emphasis on the Jewish narrative to a more global theme.

Recent comments