The biblical story of Jesus is a very long one. It reaches back to the creation of all things; it concludes with the re-creation of all things and the symbolic presence of the Lamb in the glorious city of the creator God. If we superimpose on this already complicated biblical story the church’s highly theological account of who Jesus was, is and will be, then we have a biography of massive mythical and metaphysical proportions. But in order to understand the story of Jesus we have to start not with this glorious meta-biography but with the much more modest and limited historical narrative that we find in the Gospels—in Matthew, Mark and Luke in particular.

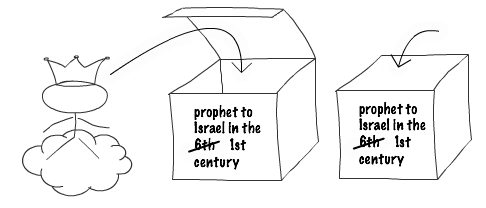

So the first thing we need to do is strip away all the conceptual trappings from the Second Person of the Trinity, the unique God-man, the exalted Lord, the pre-existent divine Logos, everybody’s personal saviour, the Jesus who has entered my heart, and we need to put him in a small box. On the outside of the box are the words “prophet to Israel in the 6th century”. We need to cross out “6th” and write “1st”. Then we need to close the box. We will have to open the box later and take Jesus out again, but for now it needs to stay closed.

Having done this, we may make an attempt at explaining roughly who he thought he was and what he thought he was doing.

Bad news and good news

The prophet Jesus announced to Israel—and only to Israel—that the “kingdom of God” was at hand. This was both good news and bad news. The bad news was that the nation was heading for a disastrous war against its Roman overlords, which would result in the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple and massive loss of life. This would not be an accident of history. It would be an act of divine justice, a judgment of gehenna—“punishment” for the nation’s deeply engrained resistance to YHWH as king. The good news was that YHWH—it is important that we use Israel’s “name” for God here—would provide a way of “salvation” for his people, a narrow path that would lead to life, though Jesus did not expect many Jews to find that path.

Spoken like a prophet

Jesus announced this coming act of divine intervention in three different ways. First, he preached and taught and argued and told stories about it, just as his Old Testament predecessors had done. Secondly, he healed the sick, raised the dead, and cast out the demons that possessed Israel as a powerful sign that YHWH was about deliver his people from their oppressors, forgive their sins, heal their profound spiritual sickness, and raise them to new life. Thirdly, he acted out the coming judgment and restoration of God: he associated with prostitutes and sinners, he calmed a storm, he confused people with parables, he rode into Jerusalem on a donkey, he cursed a barren fig tree, he started a one man riot in the temple, and so on.

The way of salvation

Jesus was clear in his own mind that the narrow path of “salvation” would be a way of suffering—it could hardly be anything else given the level of opposition from every quarter of the establishment. He may have thought of himself as the servant of Isaiah through whose faithful suffering God would redeem his “exiled” people, which would be a sign to the nations that Israel’s God was the one true God. He certainly thought of himself as the figure “like a son of man” in Daniel’s vision, who would suffer in the course of Israel’s “end-time” crisis but would be vindicated and given kingdom and authority. It was the price that had to be paid, so to speak, if the descendants of Abraham were to have a viable future.

The fellowship of the Son of Man

So Jesus believed that the way of salvation for Israel would be opened up by his own suffering, and he faced this with the conviction that his Father would not abandon him to death. But he also knew that, practically speaking, this would count for nothing if no one followed him down this narrow and difficult path leading to life. So he gathered around himself a community of renewed Israel, a group of disciples, which would continue his mission. Acting under his authority, they would proclaim throughout the towns and villages of Israel both the bad news and the good news, right through to the climactic moment of divine judgment—within a generation—when they too would be vindicated for their Christlike faithfulness.

Those who joined this prophetic community would have to take up their own crosses; they too would play the part of the suffering servant; they too would be cast in the symbolic role of the “Son of Man” who would be vindicated. They were not the church as we know it. It makes more sense to see them as a transitional community, a community of eschatological blessing, over which not even death would prevail.

An extraordinary coup

In the end Jesus, the charismatic prophet from distant Galilee, directly challenged the leadership in Jerusalem. They had forfeited the right to rule. They imposed intolerable religious and social burdens on ordinary Jews; they were hypocrites, blind guides; they were like whitewashed tombs; they consistently rejected the messengers whom God sent to them. So the seat of their power, Jerusalem and its temple, would be taken away from them, and the “kingdom” would be given to a different people, gathered from the margins of Israel, and to a different king—a king who rode humbly into the city on a donkey to mark the impending liberation of the people from oppression.

The various hierarchies conspired to suppress this extraordinary challenge to their authority, refusing to believe that he spoke legitimately on behalf of God. But Jesus was quite sure of his messianic calling and knew that history would prove him right. As he said to the high priest Caiaphas at his trial, “I tell you, from now on you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven” (Matt. 26:64). At this moment of ultimate powerlessness, the prophet from Galilee was claiming the authority not only to speak against the régime—as John had spoken before him—but to rule over this people in the place of Caiaphas and Herod and Pilate and, of course, the god Caesar.

To be continued…

Andrew: How much do you think the alleged disobedience of Israel was the result of the collective actions of the Jewish people and how much is rewritten backwards into the narrative to fit the story of the cult that divided from mainstream Judiasm?

I mean, scholars have long recognized that Matthew was written by someone from a group that was in conflict with the Pharisees at the time the book was written. Probably after the temple was destroyed, there was jockeying to decide who was going to be the real Jews. So this writer made the Pharisees the bad guys, writing disputes of his day back into the time of Jesus.

So what exactly did the Israelites do to deserve judgement other than to not accept Jesus as the messiah? Beyond that, were they more evil than any other nation?

@paulf:

Paul, that’s probably an impossible question to answer, but it cuts both ways, doesn’t it? You say that “scholars have long recognized…”. But what’s to stop us deconstructing the “scholars”, or at least their conclusion that this purported conflict with the Pharisees seriously distorted Matthew’s reading of Jesus’ controversy with Israel.

So what exactly did the Israelites do to deserve judgement other than to not accept Jesus as the messiah? Beyond that, were they more evil than any other nation?

There is much more to Jesus’ critique of Israel than that they did not accept him as messiah. The temple incident is an attack on the corruption of the whole system. The woes of Matthew 23 contain a whole spectrum of abuses. Etc.

No, they were not any more evil than other nations. But the point was that they were supposed to be more righteous than other nations. That’s Paul’s analysis. They had the Law, etc. They should have provided a benchmark of righteousness. That’s what they were chosen for. But they proved to have feet of clay.

@Andrew Perriman:

I’ve been busy, and didn’t notice your response.

What was corrupt about the temple system? The orthodox view as I’ve been taught is that the moneychanging was evil. But why? People needed something to sacrifice, they couldn’t travel with live animals to sacrifice, and those from outside didn’t have the proper currency, so a system was set up to take care of those needs.

The Jews had heated arguments among themselves about the best way to interpret the will of god, but I think that was to their credit that they were attempting to do the right thing by their god. The destruction of Jerusalem came about because they were putting faith in God to deliver them, not because they were living drunken and licentious lives.

The bad news was that the nation was heading for a disastrous war against its Roman overlords, which would result in the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple and massive loss of life.

Jesus’ public mission lasted (depending on the gospel version) from 6 months to 3 years. Assuming the shortest option, there is no evidence that “the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple” was part of the initial preaching of Jesus about the “Kingdom of God”. There is no evidence that the Cross was (inevitably) the conclusion of his mission. Only with and after Peter’s confession at Caesarea Philippi (Matt 16:13-20) the theme of death and resurrection (Matt 16:21-28) started and became predominant.

It was the price that had to be paid, so to speak, if the descendants of Abraham were to have a viable future.

What “viable future”, if the conclusion was the destruction of the temple and of Jerusalem, and the scattering of those who remained? Who were/are the “descendants of Abraham”, anyway?

So he gathered around himself a community of renewed Israel, a group of disciples, which would continue his mission. Acting under his authority, they would proclaim throughout the towns and villages of Israel both the bad news and the good news, right through to the climactic moment of divine judgment—within a generation—when they too would be vindicated for their Christlike faithfulness.

Peter and the other Apostles had all clear in their mind that their essential mission was to “witness to his resurrection” (Acts 1:21-22)

They had forfeited the right to rule. They imposed intolerable religious and social burdens on ordinary Jews; they were hypocrites, blind guides; they were like whitewashed tombs; they consistently rejected the messengers whom God sent to them.

The essential fault of the ruling elite of Israel was not to recognize their Messiah when they had him in front of them. If they had recognized him, then they would not, later, have gone after false “messiahs”, challenging Rome, and bringing destruction upon themselves.

At this moment of ultimate powerlessness, the prophet from Galilee was claiming the authority not only to speak against the régime—as John had spoken before him—but to rule over this people in the place of Caiaphas and Herod and Pilate and, of course, the god Caesar.

True. But to claim that this prophecy of Jesus to Caiaphas was fulfilled with the destruction of the temple and of Jerusalem, to claim that this is the real meaning of Jesus’ announcement “to Israel—and only to Israel—that the ‘kingdom of God’ was at hand”, when after 70 (or 135 at the latest), this announcement, this “good news”, would become totally irrelevant to national Israel is a tad … stretched … even with the proviso that “Jesus did not expect [#] many Jews to find that path”.

[#] Link leading to nowhere. Perhaps it was meant as a link to Are those being saved few? (16 November, 2009)

Recent comments