The central claim of the New Testament regarding the risen Jesus is this: because he was faithful unto death in fulfilment of his mission to Israel, the God of Israel raised him from the dead and gave him the authority, which formerly belonged to God alone, to judge and rule over the nations—meaning, at least in the historical purview of the New Testament, the nations of the Greek-Roman world.

In other words, the early church thought of Jesus principally as an exalted human being, enthroned in heaven alongside YHWH, exercising the supreme but delegated authority of YHWH over all beings which had the capacity to confess him as Lord, whether in heaven or on earth or under the earth. That, I think, is more or less how Philippians 2:9-11 should be read.

A christology of divine identity?

However, because the language of verses 10-11 has been taken from a statement about YHWH himself in Isaiah 45:23, it is often argued that Paul directly identifies Jesus with God. In Isaiah YHWH is the kyrios to whom every knee will bow, etc.; in Philippians 2:10-11 Jesus is the kyrios to whom every knee will bow, etc. Therefore, by a simple syllogism, Jesus is YHWH.

Turn to me and be saved, those from the end of the earth; I am God and there is no other. According to myself I swear: Surely, righteousness will go out from my mouth, my words will not be turned back, that to me every knee will bow, and every tongue profess allegiance to God, saying, righteousness and glory will come to him, and all those separating themselves will be ashamed. (Is. 45:22-25 LXX, my translation)

Therefore indeed God highly exalted him and favoured him with the name which is above every name, in order that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, of those in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord to the glory of God the Father. (Phil. 2:9-11, my translation)

In an essay that is available online, Richard Bauckham argues that a high Christology was possible under the conditions of Jewish monotheism “by identifying Jesus directly with the one God of Israel, including Jesus in the unique identity of this one God”. Specifically, he thinks that Philippians 2:9-11 points to a Christian reading of Deutero-Isaiah that “understood the universal acknowledgement of YHWH’s unique deity to result from the revelation of YHWH’s identity in the person and fate of his Servant”.

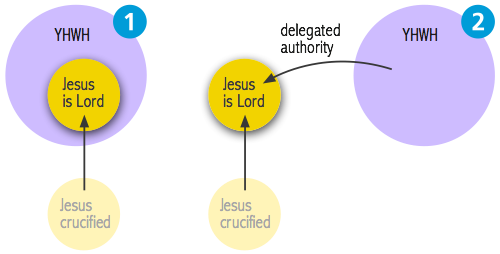

I haven’t come across the argument quite so much in the last couple of years, so perhaps it is going out of fashion. Anyway, here are my reasons for rejecting—at least as far as Philippians 2:9-11 is concerned—the divine identity paradigm (1) in favour of a delegated authority paradigm (2).

“Jesus is Lord” does not mean “Jesus is YHWH”

1. The translators of the Septuagint used kyrios both for the Hebrew word adonay, which means “Lord”, and for the name of God yhwh. But kyrios is not itself a name for God; it is not a translation of the written word yhwh. It is a translation of adonay as it would have been substituted for yhwh when the scriptures were read. Like adonay, kyrios means “lord”; it refers to a man who has authority to rule over others, to whom others are subordinated as subjects or servants. The title kyrios, therefore, seemed to pious Jews a good alternative—not an equivalent—to the unutterable name yhwh. Paul would have been well aware of the semantic difference between the two terms. YHWH was the name of God; kyrios denoted one aspect of his relation to the world.

Here’s a simple analogy. The name of the team captain is Luka. If, for whatever reason, Luka passes the captain’s armband to Ivan halfway through the game, then Ivan has been given the authority to act as captain. In a sense, the team now has two captains: Ivan is exercising the authority of captain on behalf of Luka—probably only until the end of the game when the armband will be returned to Luka. But Ivan does not become Luka; he does not share Luka’s identity.

2. The end point of the argument in both passages is not that someone is Lord but that God is glorified. The question is: how is God glorified? According to Isaiah 45, YHWH saves his people, the nations turn to him in awed response, abandoning their false gods, they bow the knee to him and profess allegiance to him, as subjects would do to a king, and as a result YHWH is glorified in the ancient world (“righteousness and glory will come to him”). According to Philippians 2:9-11, Jesus is faithful to the point of death on a Roman cross, God exalts him and gives him the name above every name, the nations bow the knee to him and profess allegiance to him as Lord, and as a result YHWH is glorified in the ancient world (“to the glory of God the Father”).

It is clear from this that Jesus does not do what YHWH was expected to do in Isaiah 45. It is not simply that Jesus is not identified with YHWH; their stories are different. YHWH delivers his people from captivity in Babylon, and the pagan nations turn to him for salvation. Jesus refuses to take the way of pagan kingship, suffers at the hands of the oppressor, but then is vindicated and instated as king. It is not what Jesus does that gets him confessed as Lord but what is done to him. It is perhaps fundamentally this narrative divergence that rules out a straightforward identification of Jesus with YHWH.

3. This is where Bauckham’s assertion about the “revelation of YHWH’s identity in the person and fate of his Servant” comes unstuck. In the Philippians passage the revelation which leads to the glorification of God among the nations is found not in the “person and fate” of Jesus but in the action of God in raising him from the dead and seating him at his right hand.

4. Bauckham’s argument relies in part on the assumption that the “name which is above every name” is “YHWH”. This seems intrinsically unlikely: it is barely intelligible that a person would create a binary identity by giving his own name to another person (see the analogy above). Most commentators, I think, would say that the name above every name is “Lord”; some argue for “Jesus”. There is no suggestion of identification in Ephesians 1:20-21, where it is said that God raised Christ from the dead and seated him at his right hand, “far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the one to come”. The writer to the Hebrews says that Jesus took his seat at the right hand of God, “having become as much superior to angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs” (Heb. 1:4). In context, this would appear to be a reference to his status as the Son “begotten” on the day of his resurrection (Heb. 1:5).

5. Bauckham thinks that in Philippians 2:10-11 Paul has exploited a distinction between Lord and God in Isaiah 45:23 LXX: the Lord says that “every knee shall bow to me” but that “every tongue shall confess to God”. In Greek Isaiah it is “God” who speaks, and the switch from “me” to “God” may anticipate the third person reference to God in the next lines: every tongue shall profess allegiance to God, “saying, Righteousness and glory shall come to him, and all who separate themselves shall be ashamed” (Is. 45:24). Besides, the distinction as Bauckham constructs it does not match Paul’s use of the quotation: Paul’s “every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father” (Phil. 2:11) is quite different from Greek Isaiah’s “every tongue shall profess allegiance to God”.

6. Jesus is the passive recipient of a status and authority that is graciously “bestowed” (echaristo) upon him. The verb charizomai implies an unequal relationship between two distinct persons, one who bestows and one who is the beneficiary. I struggle to see how we can say in the same breath that YHWH graciously bestowed on Jesus this status and authority and that Jesus is YHWH.

7. When David called on the assembly of the leaders of Israel to bless the Lord, they “blessed the Lord, God of their fathers, and bowed (kampsantes) their knees and did obeisance (prosekunēsan) to the Lord and the king” (1 Chron. 29:20 LXX). This suggests that it was quite appropriate to bow the knee to and “worship”—or better “serve”—both God and his anointed king. The is what we have in the intertextual relationship between Philippians 2:10-11 and Isaiah 45:23. Bauckham thinks that when worship is “performed by every creature in the universe… it unquestionably expresses the monolatry that was a defining feature of Jewish monotheism”. But the transfer of YHWH’s sovereignty to Jesus would account for this just as well. Verse 10 is not a reference to “every creature in the universe”. In context, the reference is to all intelligent beings (humans, angels, gods?) capable of bowing the knee and confessing that Jesus is Lord. As in Isaiah 45:18-25, the apocalpytic vision is essentially “political” rather than cosmic.

8. Three other Old Testament texts are especially used in the New Testament to account for the fact of Jesus’ lordship. He is the Son “begotten” as king on the day of his resurrection, to whom YHWH will give the nations as his heritage, to shepherd with a rod of iron (Ps. 2:7-9 LXX). He is the king greater than David seated at the right hand of YHWH to rule in the midst of his enemies (Ps. 110:1-2). And he is the “one like a son of man”, representative of the persecuted righteous in Israel, who will receive from YHWH dominion over the nations of the former pagan empire (Dan. 7:13-14).

In none of these templates is the authority to rule and be served given on the basis of an equivalence of identity between YHWH and the king or lord. The point is rather that YHWH will establish, defend, and empower the one whom he has appointed to rule as Israel’s king under difficult “political” conditions throughout the coming ages. The idea is found everywhere in the New Testament (e.g., Matt. 28:18; John 3:35; 13:3; Acts 2:36; 17:31; Rom. 1:3-4; 14:9; 1 Cor. 15:27; Eph. 1:10, 20-22; Col. 2:10; Heb. 1:2; 2:8; 1 Pet. 3:22).

9. Paul also quotes Isaiah 45:23 in the context of his exhortation to Jewish and Gentile believers in Rome not to judge one another over relatively unimportant matters of religious observance. Jesus died and lived in order that “he might be Lord (kyrieusēi) both of the dead and of the living” (Rom. 14:9). This lordship has reference to the present relationship between the believers as servants and the one who is Lord or master over them (Rom. 14:4). It is not confused with their responsibility towards God. They follow certain practices (eating or not eating particular foods, observing special days or not) as to the Lord (kyriōi), but they do so giving thanks to God. While Christ as Lord is the one who will enable them to remain faithful in the meantime (Rom. 14:4), at some point in the future they will have to stand before the judgment seat of God, and each will have to give an account of himself or herself to God (Rom. 14:10-12). It is this future judgment that is explained by reference to the Isaiah passage:

…for it is written, “As I live, says the Lord, every knee shall bow to me, and every tongue shall confess to God.” (Rom. 14:11)

The argument is that they have a master who sustains them in their witness through to day of Christ, when the nations of the empire will acknowledge both that there is only one God, not many gods, and that there is only one Lord, not many lords (cf. 1 Cor. 8:6).

This is not an unevangelical position to take

So I remain unconvinced that the acclamation of Jesus as Lord presupposes the identification of Jesus with YHWH. The logic is rather that YHWH has transferred the authority to judge and rule over the idolatrous nations to his Son: Jesus is now Kyrios on behalf of God and to the glory of God. YHWH will manage the relationship between his people and the nations, for the rest of history, through the Son seated at his right hand.

This is not, I stress, an unevangelical position to take. On the contrary, it gets to the heart of the historically-oriented evangel in the New Testament—the gospel as Paul frames it, for example, in Romans 1:1-4:

Paul, a servant of Christ Jesus, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God…, concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh and was declared to be the Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord.

The paradigm certainly created a conceptual challenge for the Greek church as it lost touch with the apocalyptic origins of its faith—a challenge which was eventually resolved by means of the doctrine of the Trinity. The narrative of delegated authority was collapsed into the ontology of Jesus’ identity as God the Son. History lost out to metaphysics.. But I do not think that this solution was anticipated, as such, in the New Testament narrative of Christ’s exaltation and lordship.

I see that the Lord Jesus is God based on the fact that universal worship is rendered unto Him. This connects with what was also spoken of by Daniel 7:13-14.

There are four passages in the New Testament where “bow” (kamptō) is used and each one of them refers to worship (Romans 11:4; 14:11; Ephesians 3:14; Philippians 2:10). Since worship is properly due unto God alone and the Lord Jesus properly receives it this proves He is God. Thus the “Lord” as found in Philippians 2:11 is to be taken in its full significance.

@Marc Taylor:

Do you think you could give consideration to the whole argument in the post?

The New Testament evidence for the use of kamptō is very limited. There are also only a few relevant texts in the LXX, of which one is 1 Chronicles 29:20:

And David said to all the assembly, “Bless the Lord, your God,” and all the assembly blessed the Lord, God of their fathers, and bowed (kampsantes) their knees and did obeisance (prosekunēsan) to the Lord and the king.”

This is obviously of interest. It shows that it was appropriate to bow the knee to and “worship” both God and his anointed king at the same time. The is exactly what we have in the intertextual relationship between Philippians 2:10-11 and Isaiah 45:23.

@Andrew Perriman:

2 Chronicles 31:8

When Hezekiah and the rulers came and saw the heaps, they blessed the LORD and His people Israel. (NASB)

Blessing the Lord means offering Him worship but that doesn’t mean Hezekiah and the rulers rendered worship unto the people of Israel.

2 Chronicles 35:3

He also said to the Levites who taught all Israel and who were holy to the LORD, Put the holy ark in the house which Solomon the son of David king of Israel built; it will be a burden on your shoulders no longer. Now serve the LORD your God and His people Israel. (NASB)

Josiah (cf. 2 Chronicles 35:1) did not mean that the service (worship) that ought to be given unto God was also to be done unto the people of Israel.

In all three passages (1 Chronicles 29:20; 2 Chronicles 31:8 and 2 Chronicles 35:3) worship is only offered unto God.

Every instance of kamptō is used in reference to worship. There is no reason therefore to somehow water it down especially in view of its absolute usage (2:11).

@Marc Taylor:

Your examples simply demonstrate that blessing and service could be directed both to God and to the people—just as service rendered to the “one like a son of man” doesn’t make him God. It is simply wrong to say that in 1 Chronicles 29:20 “worship” is offered only to God. “Worship” is an inadequate English translation because we wouldn’t now use it with reference to a monarch. But in the thought-world of the Old Testament it was entirely appropriate to “bow the knee” and “do obeisance” both to divine and to human figures.

@Andrew Perriman:

One is worship while the other is not. The other passages from 2 Chronicles demonstrates it is not used that way in 1 Chronicles 29:20.

2 Corinthians 8:5

and this, not as we had expected, but they first gave themselves to the Lord and to us by the will of God. (NASB)

Giving themselves to the Lord means to worship the Lord. But giving themselves to other Christians does to entail worshiping them.

@Marc Taylor:

That they “gave themselves” to the Lord does not mean that they “worshipped” the Lord. It means that they {dedicated themselves” to the Lord (see BDAG s.v. didōmi, “10. to dedicate oneself for some purpose or cause”). That they “gave themselves” to the apostles means that they “dedicated themselves” to the apostles. The meaning of heautous edōkan doesn’t change. Obviously they didn’t worship the apostles, but that’s not what Paul is saying.

@Andrew Perriman:

It entails the worship of the Lord (the Lord being Jesus).

That these believers so dedicated their lives in spiritual sacrifice (which is worship; cf. Romans 12:1) to the Lord Jesus (cf. 8:9) demonstrates that He is God.

1. BDAG (3rd Edition): Citing 2 Corinthians 8:5 reads: give oneself up, sacrifice oneself (didōmi, page 242).

2. Heinrich Meyer: but themselves they gave, etc. An expression of the highest Christian readiness of sacrifice and liberality, which, by giving up all individual interests, is not only a contribution of money, but a self-surrender, in the first instance, to the Lord, since in fact Christ is thereby served, and also to him who conducts the work of collection, since he is to the giver the organ of Christ.

https://www.studylight.org/commentaries/hmc/2-corinthians-8…

There giving themselves to the Lord Jesus involves a total surrender.

Joseph Thayer: I give myself up as it were; an hyperbole for disregarding entirely my private interests, I give as much as ever I can: 2 Corinthians 8:5 (Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, didōmi).

http://biblehub.com/greek/1325.htm

So not only is the Lord Jesus being worshiped in Philippians 2:11, but the same thin is taught in 2 Corinthians 8:5 — as well as throughout the New Testament.

1. H. Schlier: kamptein gony (gonata) is the gesture of full inner submission in worship to the one before whom we bow the knee. Thus in R. 14:11 bowing the knee is linked with confession within the context of a judgment scene, and in Phil. 2:10 it again accompanies confession with reference to the worship of the exalted Kyrios Jesus by the cosmos (TDNT 3:594, kamptō).

2. Joseph Thayer: to bow the knee, of those worshipping God or Christ: Ro. 11:4; Eph. 3:14; Ro 14:11 (1 K. 19:18); Phil. 2:10 (Is. 45:23) (Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, gony, page 120).

3. Murray Harris: Object of worship (Phil. 2:10-11) (Jesus as God: An Outline to the New Testament Testimony to the Deity of Christ, page 316).

@Marc Taylor:

Marc, this line of argument really doesn’t work exegetically. No dictionary gives “worship” as a meaning for didōmi with the reflexive pronoun. Giving oneself up, like bowing the knee, is a way of speaking about the self-dedication or submission of a person to another. The extremity of that self-dedication or submission does not in itself determine how the indirect object is to be understood. I can give myself absolutely to my wife or my boss or my king or my God. Again, 1 Chronicles 29:20 is incontestable proof that it was acceptable for Jews to bow the knee and do obeisance to their king as distinct from YHWH.

Notice that Meyer does not differentiate between “to the Lord” and “to him who conducts the work of collection”. Meyer proves my point. The self-giving is the same in each case. It’s simply that the Lord comes first, for obvious reasons.

@Andrew Perriman:

If you give yourselves to others God is always in the background (see Meyer above). — “he is to the giver the organ of Christ.”

This is what Murray Harris also affirmed: Clearly they recognized that dedication to Christ involves dedication to his servants, and that dedication to them was in reality service for Christ (Slave of Christ: A New Testament Metaphor for Total Devotion to Christ, page 104).

@Marc Taylor:

Proverbs 24:21

My son, fear the LORD and the king;

Do not associate with those who are given to change. (NASB)

To “fear the Lord” encompasses worshiping the Lord, but this doesn’t mean the king should be worshiped.

Psalm 34:11

Come, you children, listen to me; I will teach you the fear of the LORD. (NASB)

1. Watson’s Biblical and Theological Dictionary: Fear is put for the whole worship of God: “I will teach you the fear of the Lord” Psalms 34:11; I will teach you the true way of worshipping and serving God. (Fear)

http://www.studylight.org/dictionaries/wtd/view.cgi?n=668

In the NT we are told that the Lord, in reference to Jesus, ought to be feared which means He is to be worshiped (Acts 9:31; 2 Cor. 5:11; Col. 3:22; cf. Eph. 5:21; 6:5).

@Marc Taylor:

Ok, I haven’t really jumped into this exchange because I feel like you’re not going to be convinced no matter what anybody says, but when I saw this, I just had to point out that your explanation applies just as well to Jesus and God — that dedication to God also means dedication to His servants, that he is the “organ of God,” etc.

All the things you are falling back on to explain why the word doesn’t mean “worship” of David as divine can apply equally well to Jesus. The only difference is that you know David isn’t divine, therefore there’s an explanation as to why worship doesn’t mean worship. But you are already committed to Jesus as divine, and that’s why the same arguments don’t apply?

I mean, can’t you see that you are significantly begging the question in your argumentation?

@Philip Ledgerwood:

I too jumped into this conversation with the feeling that no matter what anyone says concerning the worship of the Lord Jesus as God you wouldn’t be convinced.

I gave 4 other Bible verses ( 2 from 2 Chronicles) that demonstrate that 1 Chronicles 29:20 does not mean David was worshiped.

Furthermore, David is not referred to as the “Lord” in the New Testament in which He is to be “feared” (which means worship) as God. The Lord Jesus, in several NT passages, is.

1. Acts 9:31

David Peterson: Since ‘the Lord’ is most obviously the risen Lord Jesus in 9:5, 10, 17, 27, 35, 42 the reference is arguably the same as in 9:31. Thus the fear of the Lord, which is such an important aspect of OT piety in relation to the God of Israel, is here applied to the relationship between the glorified Jesus and his disciples. Cf. W. Mundle, NIDNTT 1:621-624 (The Acts of the Apostles, Pillar New Testament Commentary, page 318, footnote #80).

2. Colossians 3:22

Douglass Moo: The “fear of the Lord” is, of course, a prominent them in the Old Testament, combing a sense of appropriate awe in the presence of God in submission to his will. But the theme is by no means absent from the New Testament (e.g., 2 Cor. 7:1; 1 Pet. 2:17; Rev. 11:18; 14:7; 15:4; 19:5), where, in a move typical of the “Christological monotheism” of the early church, the Lord is sometimes defined as Christ (Acts 9:31; 2 Cor. 5:11; Eph. 5:21). This is certainly the case here, as the high Christology of the letter to the Colossians as a whole is again brought to bear on the ordinary situation of the Christian household (The Letters to the Colossians and Philemon, The Pillar New Testament Commentary, page 311).

People did not call upon the name of the Lord (YHWH) in reference to David, but they did in reference to the Lord Jesus in several passages (Acts 9:14, 21; 22:16; Rom. 10:12-14; etc.) This means He was worshiped as God.

J. C. O’Neill: To call on the name of the Lord Jesus was to worship the God of Israel (The Use of KYRIOS in the Book of Acts, Scottish Journal of Theology, Volume 8, Issue 2, c. June, 1955, page 172).

People did not proclaim “the will of the Lord be done” in reference to David, but they did do unto the Lord Jesus knowing that as God His will is supreme (Acts 21:14; 1 Cor. 4:19; 16:7; Eph. 5:17).

People did not sanctify David as Lord in their hearts for they knew this was worship due only unto God (Isaiah 8:13; cf. Matthew 6:9). And yet we are to engage in this worship to the Lord Jesus (1 Peter 3:15).

Many more examples can be given for those with hearts willing to see.

@Marc Taylor:

So, in Matthew 10:26-28, do you think Jesus is warning his followers not to worship their persecutors as divine, or is he saying not to be afraid of them?

In 1 Peter 2:18, he tells slaves to fear (phobo) their masters (despotai), which is also a word used for Lord/God in Luke 2:29 and Acts 4:24. Do you believe Peter is instructing slaves to worship their masters as divine? The fear is there and the same word used for God is there — in fact, it’s the word used in the -one- passage you quoted about the fear of the Lord that specifically says it’s about Jesus, Eph. 5:21.

In Acts 26:32, Agrippa points out that Paul has “called upon” (epekekleto) Caesar. Does this mean Paul worshipped Caesar as divine like his pagan counterparts? The same word is used when Paul appeals to anyone else as well as Paul’s own recounting of his journey.

I’ll bet people told David, “Thy will be done” all the time. That’s a very common thing to say to royalty and has been for centuries long after the Bible was written. They probably didn’t say that in regard to natural circumstances as in your passage because David was not sovereign over things like life events, weather, etc.

Obviously holiness is also an attribute ascribed to people. Exodus 19:6 makes this a defining characteristic of Israel, and in the New Testament, 1 Peter again calls believers in 2:9 a “royal priesthood” and a “a holy nation.”

The thing is, your arguments only work if you decide -in advance- that Jesus is divine. Every single example you offer is something that the Bible elsewhere applies to people who are absolutely not divine beings. If you want to establish Jesus’ divinity, you’re going to have to do better than “this word/phrase is used for God and also for Jesus,” and then when people point out those same words or phrases are used for other people, say, “Well, obviously that just means they’re representatives of the divine. I mean, they didn’t use these OTHER phrases to talk about that person.”

Jesus is the centerpiece of the New Testament. He gets more air time than anyone else. He has more said about him than anyone else. Unfortunately, for your case, the things said about him are often said about other people in other places, just not all gathered into one person like we’d expect in the New Testament.

The whole argument-by-concordance approach is just very unconvincing. You’re going to need to exegete at some point.

@Philip Ledgerwood:

Matthew 10:26-28

They are not referred to as “Lord” to whom to fear. Furthermore, Christians are viewed as slaves of Christ which demonstrates that they worshiped the Lord Jesus as God.

Murray Harris: The very existence of the phrase ‘slave of Christ’ alongside ‘slave of God’ in New Testament usage testifies to the early Christian belief in Christ’s deity. Knowing the expression ‘slave of the Lord’ from the Septuagint, several New Testament writers — John, Peter, Paul, James and Jude — quietly substitute ‘Christ’ for ‘the Lord’, a substitution that would have been unthinkable for a Jew unless Christ was seen as having parity of status with Yahweh (ibid., page 134). Indeed, according to the Jewish Encyclopedia of the Bible (1901), “devoted worshipers of the Deity were commonly designated as God’s servants…” (Servant of God)

https://www.studylight.org/encyclopedias/tje/s/servant-of-g…

1 Peter 2:18

These masters to whom Peter referred to are not elsewhere used in reference to prayer as Christ is (see my previous post). Big difference.

Christ is thus omniscient (God) in that He fully knows the hearts of those who pray unto Him.

Acts 26:32

The differences between how this same word is used in reference to the Lord Jesus are numerous. The Lord Jesus hears and already knows the prayers by those who pray unto Him even when it is done silently when it arises within their hearts. The same can not be said concerning Caesar’s ability to hear what Paul spoke at that precise moment — he wasn’t able to. One must also consider how a Greek word is used in context. Indeed, concerning the word deomai (Strong’s #1189) we see that in Luke 9:40 a man “begged” (ἐδεήθην) Christ’s disciples. This doesn’t mean he prayed to them even though deomai is used in Luke 10:2 concerning praying (δεήθητε) to the Lord of the harvest. Notice as well that Paul’s verbal appeal to Caesar pales in significance to what Stephen expressed in Acts 7:59-60. Stephen called out to the Lord Jesus to receive his spirit. This carries with it the idea that the Lord Jesus is God the Creator (cf. Ecclesiastes 12:7).

Nowhere does the Bible say “The will of the Lord be done” in reference to David in any comparison to what we see in Acts 21:14.

The fact that the Lord Jesus is the proper recipient of just one prayer necessitates that He is God. Since the Bible has quite a few examples that He is the proper recipient of prayer to deny He is God is simply inexcusable.

@Marc Taylor:

Ok, so now Jesus is divine because people pray to him.

So, your argument is now that a person must be considered to be God IF he is called Lord AND you are told to fear him AND you worship him AND you can be his servant AND you sanctify him as holy AND you act in his name AND you do his will AND you pray to him. Might as well throw the virgin birth in there while you’re at it. AND their name starts with “J” AND rhymes with “rhesus.”

Jesus obviously differs in the sense that the authority delegated to him is God’s authority. That’s why he can forgive sins, for instance. David can’t do that either, but the crowd is astounded that God gave that authority to a human being; they are not astounded because it proves Jesus is God.

The verses we have that -imply- prayer to Jesus, well, Jesus himself explains that he will do what his disciples ask because he is going to the Father, and he will do what they ask in his name so that the Father might be glorified in the Son (John 14:12-14). It’s a powerful declaration of differentiation. If Jesus answers a request, how is the Father glorified in the Son? If the Son is God, what does the Father have to do with answering requests to Jesus?

So far, every single example you have summoned in terms of title, etc. easily applies to non-deities, and your explanations of this have boiled down to the fact that the exact same phrases and sentiments do not connote divinity literally everywhere else they appear except in reference to Jesus. You have yet to explain why this is or why titular references to Jesus should be interpreted completely differently than everywhere else.

Jesus has special things attributed to him because God has given him all authority in heaven and on earth and made him both Lord and Christ (Acts 2:36). God did not make Jesus God and Christ. He made him Lord and Christ. But because Jesus is God’s delegated agent, he can say and do things that God has the power to say and do, and -that- part is definitely different than every other human example — on that we agree.

None of this proves Jesus is -not- divine or -not- God; it’s just to demonstrate that you have really weak reasons for saying so.

@Philip Ledgerwood:

Let me help you out with this.

Here is what the NIDNTT and the NIDOTTE say about prayer:

1. New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology (NIDNTT): In prayer we are never to forget whom we are addressing: the living God, the almighty one with whom nothing is impossible, and from whom therefore all things may be expected (2:857, Prayer, H. Schonweiss).

2. New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis (NIDOTTE): To pray is an act of faith in the almighty and gracious God who responds to the prayers of his people (NIDOTTE 4:1062, Prayer, O. A. Verhoef).

That the Lord Jesus is the proper recipient of prayer proves He is God.

@Marc Taylor:

So, now your argument is:

1. There are a couple of verses that imply you can pray to Jesus.

2. A couple of theological dictionaries say you can only pray to God.

3. Ergo, Jesus is God.

@Philip Ledgerwood:

There are quite a few verses that teach the Lord Jesus is God. Prayer, as properly defined, teaches that for the believer only God is to be prayed to.

Yes, this roves the Lord Jesus is God.

@Philip Ledgerwood:

Phil is correct and the argument looks like this:

1. Jesus is tempted… Mt 4:1

2. God cannot be tempted… Jas 1:13

3. Ergo, Jesus is not God. *_*

@davo:

First, this totally ignores the fact that the Lord Jesus is the proper recipient of prayer which demonstrates He is God. In addition to the two citations I supplied above here are a few others:

1. Arland J. Hultgren: Prayer, the act of petitioning, praising, giving thanks, or confessing to God (Harper’s Bible Dictionary, Prayer, page 816).

2. Samuel E. Balentine: In sum, both the OT and the NT portray prayer as a principal means by which Creator and creature are bound together in an ongoing, vital, and mutually important partnership (Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, Prayer, page 1079).

3. E. P. Clowney: Prayer is communication with God in worship (New Dictionary of Theology, Prayer, page 526).

More can be supplied if need be.

Theos (God) primarily (although not exclusively) refers to the Father. God the Father can not be tempted.

Did you ever notice that from the very beginning the book of James refers to believers as both slaves of God and Jesus (James 1:1)?

Murray Harris: The very existence of the phrase ‘slave of Christ’ alongside ‘slave of God’ in New Testament usage testifies to the early Christian belief in Christ’s deity. Knowing the expression ‘slave of the Lord’ from the Septuagint, several New Testament writers — John, Peter, Paul, James and Jude — quietly substitute ‘Christ’ for ‘the Lord’, a substitution that would have been unthinkable for a Jew unless Christ was seen as having parity of status with Yahweh (Slave of Christ: A New Testament Metaphor for Total Devotion to Christ„ page 134).

Hi Andrew,

This may be of interest. James McGrath (also an avid blogger) wrote an article for the Journal of Biblical Studies on the “two powers” view of early judaism and how it does or doesn’t relate to the issue of identity vs. delegation:

https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?artic…

What I’m exploring right now is how Christendom, by identifying Christ with OT YHWH, appropriated the Chosen People-Promised Land metaphor. It was used by Europeans to consciously and sometime unconsciously expropriate Indigenous lands. Have you addressed the legitimacy of Christendom anywhere? I distinguish between Christ, Christianity and Christendom which has used the Gelasian theory of two equal but separate powers (two swords document). I don’t think this is what Christ had in mind in his teaching about the mustard seed or the lost pearl. In fact one has to wonder about the legitimacy of the Old Testament itself. Was it literal? Did God decree the genocide of the surrounding nations? Is it the God with whom Jesus identified?

@Bruce Dayman:

Bruce, I can’t answer all these questions. I think that it makes good sense historically to understand the conversion of the Greek-Roman oikoumenē as the “fulfilment” of New Testament expectations regarding the vindication of the early church and the rule of Christ over the nations.

Such a historical reading suggests that Christendom was of much the same kind theologically as national Israel only bigger. In the Old Testament God established Israel itself as a distinct political entity in the midst of the local nations. In the fourth century God established his reign over the nations of the Roman empire, not by violence but through the faithful testimony and practice of the churches.

So we go from Israel as a priestly people in the midst of the nations to the churches as the new priesthood for an empire that has been convinced that there is one true living God who raised his Son from the dead.

How Christendom subsequently managed the various challenges inherent in its historical existence is another matter, but this is where the analogy with Old Testament Israel is relevant, it seems to me. Political entities always have to deal with conflict, and priesthoods always struggle both to maintain the integrity of their vocation and to hold rulers, etc., accountable.

The point is that it’s always the story of God managing the troubled existence of his people in history. The difficult and unprecedented situation that the church finds itself in today is just another chapter in that story.

Very good article Andrew. I have come to these same conclusions myself over the years. Jesus was a human being who died for our sins and was resurrected and exalted by God to his right hand. God gave authority to the resurrected Jesus as Lord over the nations. The 2nd Temple understanding of “son of God” as used in the Synoptic gospels simply meant “the King of Israel” as in Psalm 2. This was just another way of saying Messiah. It is what Peter confessed in Matthew 16 — “you are the Messiah — the son of the Living God.” The death, resurrection and exaltation of Jesus as Lord of the nations is the essential gospel message that Paul proclaimed as you brought out in Romans 1:3-4.

Have you read James D.G. Dunn’s work on “Christology in the Making” ? I found his exposition of Philippians 2:5-11 as an “Adam” Christology to be very good. In other words, Philippians 2:5-11 is an echo of Genesis 1:27 (as as of Isaiah 45 as you bring out) where Adam was made in the form and image of God. Adam in his disobedience tried to be like God (following the words of the serpent) but Jesus although he was the second Adam and was in the form of God did not grasp at God’s authority. In the end, because he obeyed perfectly even to the point of death God gave him authority greater than any human and gave him the name Lord. This is in contrast to what happened to Adam.

@Bill Benninghoff:

Thanks, Bill. I have reservations about Dunn’s Adam-christology. It’s hard to connect morphē theou with “image of God”, and the parallel with morphēn doulou further complicates things. I think the immediate contrast is with a figure such as the Prince of Tyre in Ezekiel 28—that is, with the oriental divine ruler type, who makes himself equal to God. The hubris of the Prince of Tyre is explained in Adamic terms, but this is at one remove from the portrayal of Christ’s alternative path to kingship.

@Andrew Perriman:

Thanks Andrew for the quick reply. I’ll think about that…By the way, I’m interested in your comment that the euangelion family of words does not show up in John’s Gospel. Can you point me to a link where you’ve written on that in more depth?

-Bill

@Bill Benninghoff:

Sorry, Bill, I’m not sure what you’re referring to here: “your comment that the euangelion family of words does not show up in John’s Gospel”.

@Andrew Perriman:

in nt, when you have something like:

“ask in my name….”

is it something like, “hey jesus, can you tell the father that i want to pass my gcse exam” ?

so is jesus being used not as an object of worship, but as an object who conveys message to the father ?

@richard:

Here’s a couple of posts that might help:

I suggested in the first one that prayer “in the name of Jesus” is not asking Jesus to intercede (though that idea is perhaps found in Hebrews) but “an appeal to God on the strength of Jesus’ death and exaltation”. But there might be a better way of understanding it.

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew, Your comment about the euangelion family of words not appearing in John’s Gospel is here in your article “Is Jesus God or is Jesus Lord?”:

“…There are certainly texts in the New Testament which lend themselves to the later line of thought. Many of them are in John, which as I noted before does not have the euangelion word group in it (a more significant fact than you might think), but which is the primary source document for those who wish to defend the orthodox Trinitarian position. I made some remarks on the use of John for this purpose in the original post.”

-Bill

I fully agree that it is wrong to resolve the relation between Jesus and YHWH in terms of “Paul’s Christology of Divine Identity”, as R. Bauckham does (Jesus = YHWH). I also mostly agree with the way you examine the relation between Is 45:22-25 and Phil 2:9-11, where the passage from Isaiah is clearly quoted (with some adaptations).

The problem with Paul, though, is that he does not simply refer to Jesus as kyrios, but even as eis kyrios (1Cor 8:6) an expression that, apart from the word order (eis kyrios vs kyrios eis) is identical to the expression used for YHWH in Deut 6:4 (LXX — but the original Hebrew expression YHWH ‘echad says exactly the same). As concluded in my post Who is the “one Lord”, for Paul?:

I suspect that [not so much Paul’s (lack of) respect for Moses’ Law or the question of the resurrection, but] Paul’s affirmation that (the resurrected, ascended and exalted) Jesus Christ was (had become?) eis kyrios, was considered by the orthodox Jews Paul’s peculiar heresy.

[1] The paradigm [proposed by Paul in Romans 1:1-4 ] certainly created a conceptual challenge for the Greek church as it lost touch with the apocalyptic origins of its faith—a challenge which was eventually resolved by means of the doctrine of the Trinity. [2] The narrative of delegated authority was collapsed into the ontology of Jesus’ identity as God the Son. History lost out to metaphysics.

Hey, not so fast, you, from 1 to 2!

The “trinity” (first subordinationist, then eventually egalitarian) was not so much adopted by the “church as it lost touch with the apocalyptic origins of its faith”, but so as to reconcile the de facto ditheism, introduced by Justin Martyr, with the scriptural monotheism retained by the church.

The authority Jesus has is not simply “delegated”: Jesus is the “incarnation” of YHWH’s dabar (logos, Word) or, to put it differently, Jesus shares in the very same dabar-YHWH, which (which …) is NOT a person, BUT an essential attribute of the One and Only personal God.

The argument relies on the assumption that the title Κύριος (Lord) in Phil. 2:9–11 is merely a functional designation of authority and not an indication of divine identity. However, this interpretation is inconsistent with the Jewish monotheistic context in which Κύριος is used. The LXX consistently uses Κύριος to translate the Tetragrammaton (YHWH), especially in contexts of divine worship and sovereignty. For example, Isa. 45:23 in the LXX declares that “to me every knee shall bow, every tongue shall confess,” with Κύριος used for YHWH. By applying this language to Jesus in Phil. 2:10–11, Paul unmistakably includes Jesus within the divine identity of YHWH. In Jewish monotheism, acts of bowing the knee and confessing allegiance (exomologeō) signify worship reserved for YHWH alone (Isa. 42:8). Paul’s application of these acts to Jesus would be idolatrous if Jesus were not fully divine. This is not a mere delegation of authority but a clear identification of Jesus with YHWH. The “name above every name” (Phil. 2:9) is best understood as a reference to the divine name YHWH. While Κύριος is used functionally in some contexts, in Phil. 2, it signifies Jesus’ participation in divine sovereignty and identity, as evidenced by the universal worship directed to him.

The claim that Jesus’ lordship glorifies God the Father does not negate Jesus’ divine identity. Instead, it underscores the unity and shared glory within the Godhead. In John 5:23, Jesus states that “all may honor the Son just as they honor the Father.” This shared glory does not diminish the Father but magnifies the unity of their divine nature. Isa. 45:23 declares that all nations will bow to YHWH as an act of exclusive worship. In Phil. 2, Paul applies this directly to Jesus, demonstrating that the universal worship of Jesus brings glory to the Father because the Son and the Father are one in divine essence. Jesus’ exaltation (Phil. 2:9) is not merely the result of delegated authority but the public acknowledgment of his divine identity, which he willingly set aside during the Incarnation (Phil. 2:6–8). This exaltation glorifies the Father by revealing the Son’s divine nature.

The alleged “narrative divergence” between YHWH’s deliverance of Israel in Isa. 45 and Jesus’ exaltation in Phil. 2 misunderstands the typological fulfillment of OT prophecies in the NT. Jesus fulfills the role of YHWH in Isa. 45 by being the one to whom every knee bows and every tongue confesses. His mission as the suffering servant (Isa. 53) culminates in his exaltation as the universal Lord, uniting the narrative threads of YHWH’s sovereignty and the servant’s obedience. The narrative differences reflect the economic roles of the Father and the Son in salvation history, not a distinction in divine essence. The Son’s obedience and exaltation reveal his divine identity and glorify the Father, consistent with Trinitarian

The argument that “the Name above every name” refers to Lord (Κύριος) rather than YHWH fails to account for the Jewish understanding of Κύριος in the context of Isa. 45. In Jewish monotheism, “the Name above every name” refers to YHWH’s unique identity and sovereignty. By granting this name to Jesus, God the Father publicly affirms Jesus’ equality with himself. Eph. 1:20–21 and Heb. 1:4 describe Jesus’ exaltation but do not negate his preexistent divine identity. The Son’s receiving of a “more excellent name” (Heb. 1:4) reflects the Incarnation, where his divine identity is revealed and acknowledged in a new way.

The distinction between YHWH and God in Isa. 45:23 does not undermine Paul’s application of the passage to Jesus. Rather, it highlights the shared divine identity of the Father and the Son. Paul uses the Isa. passage to show that the worship and allegiance due to YHWH are directed to Jesus. The difference in wording (“confess to God” vs. “confess that Jesus is Lord”) reflects the economic relationship within the Trinity, not a denial of Jesus’ deity.

The claim that Jesus’ exaltation implies an ontological inequality with the Father misinterprets the kenosis (self-emptying) of Phil. 2:6–8. Jesus’ exaltation reflects his obedience and the acknowledgment of his divine identity, not a promotion from humanity to divinity. As the eternal Son, he willingly humbled himself, and his exaltation affirms his intrinsic equality with the Father (John 17:5). The verb charizomai (bestowed) signifies the public acknowledgment of Jesus’ divine authority and name after his redemptive work, not a change in his nature.

The analogy to 1 Chron. 29:20 fails because the context of Phil. 2:10–11 involves universal, cosmic worship, which is reserved for God alone. Phil. 2 describes every being “in heaven and on earth and under the earth” bowing to Jesus. This cosmic scope exceeds the reverence shown to David and is consistent with worship directed to YHWH in Isa. 45:23.

While OT kings and figures are granted authority, they are never objects of universal worship as Jesus is in the NT. The worship described in Phil. 2:10–11 and Revelation 5:13–14 involves universal adoration of Jesus alongside the Father. This is unparalleled in the OT and signifies Jesus’ inclusion in the divine identity.

Rom. 14:11 applies Isa. 45:23 to Jesus, affirming his role as both Lord and Judge. Jesus’ lordship and judgment are consistent with his divine identity. The distinction between the Father and the Son in judgment reflects their economic roles, not an ontological hierarchy (John 5:22–23).

@fghjk5678:

I doubt I will get round to addressing every point you make in your comments here, but here’s a starter looking at the clause with exomologēsētai in Philippians 2:11.

Bauckham’s framework emphasizes the inclusion of Jesus within the unique divine identity of YHWH as articulated in Jewish monotheism, rather than conflating the two persons of the Father and the Son. Paul deliberately reinterprets the Shema (Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one). In 1 Corinthians 8:6, he includes both the Father and Jesus Christ within the Shema by distinguishing their roles—”one God, the Father, from whom all things are,” and “one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom all things are.” This does not introduce “ditheism” but affirms the unique divine identity shared by the Father and the Son. The phrase “heis Kyrios” (“one Lord”) in 1 Corinthians 8:6 corresponds to the “YHWH echad” in Deuteronomy 6:4, making it clear that Paul identifies Jesus as YHWH in function and essence. Paul’s affirmation of Jesus as “one Lord” in the context of Jewish monotheism reflects not heresy but a rearticulation of monotheism in light of Jesus’ resurrection and exaltation. This reinterpretation aligns with the early church’s understanding of Jesus as fully divine yet distinct from the Father, consistent with Trinitarian theology.

The suggestion that Trinitarian doctrine emerged to resolve de facto ditheism is historically and theologically inaccurate. Early Christian theology, including Justin Martyr’s, was firmly rooted in monotheism, and the development of Trinitarian doctrine was a response to the full revelation of God in Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit, not an attempt to reconcile “two gods.” Justin’s theology is often misrepresented as ditheistic because of his emphasis on the Logos. However, Justin explicitly affirms the unity of God and the Logos: “He is distinct in number, not in will” (Dialogue with Trypho, 56). The Logos theology reflects the eternal relationship within the Godhead, where the Son shares fully in the divine essence without dividing or duplicating it. The doctrine of the Trinity developed not to resolve ditheism but to articulate the biblical witness that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are distinct persons who share one divine essence. The early church fathers, including Athanasius and the Cappadocians, consistently defended monotheism against any notion of polytheism or ditheism. The claim that the Trinity evolved from subordinationist to egalitarian theology oversimplifies historical development. Early subordinationist language (e.g., Origen) was not an ontological subordination but a functional subordination within the economy of salvation. Trinitarian theology clarified the ontological equality of the persons of the Trinity while maintaining their distinct roles.

The assertion that Jesus is merely the incarnation of YHWH’s “dabar” (Word) as an attribute, rather than a distinct divine person, undermines the New Testament witness and fails to account for the personal nature of the Logos. The Prologue of John explicitly identifies the Logos as both God (theos) and a distinct person in relation to the Father (pros ton Theon). The Logos is not merely an attribute but an eternal, divine person who became flesh (John 1:14). This personal nature is evident in the Logos’ role in creation (“through him all things were made,” John 1:3) and revelation (“we have seen his glory,” John 1:14). The Son is described as “the radiance of God’s glory and the exact imprint of his nature” (charaktēr tēs hypostaseōs autou, Hebrews 1:3), affirming that Jesus shares the divine essence while being a distinct person. In Philippians 2:6–11 the kenosis (self-emptying) of Christ presupposes his preexistent divine identity. The exaltation of Jesus (Phil. 2:9) is not the bestowal of divinity but the public recognition of his eternal divine identity and the vindication of his incarnational work. The worship directed to Jesus in Philippians 2:10–11 echoes Isaiah 45:23, affirming that Jesus shares in YHWH’s identity and sovereignty. The identification of the Logos as an attribute rather than a person is inconsistent with both Scripture and early Christian theology. The Logos is eternally begotten, not created, and is co-equal with the Father in essence and glory. The personal nature of the Logos is foundational to the doctrine of the Trinity.

The claim that Trinitarian theology prioritizes metaphysics over history misunderstands the purpose of the doctrine. The Trinity is not a philosophical construct but a theological articulation of the historical revelation of God in Christ and the Spirit. Trinitarian doctrine arises from the historical reality of the Incarnation and Pentecost. The church recognized the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as distinct persons who acted in history while sharing one divine essence. The distinction between “delegated authority” and “ontological identity” is false. Jesus’ authority is both delegated in his incarnate role and intrinsic to his divine nature. The historical exaltation of Jesus reflects his eternal divine identity, revealed in the economy of salvation. Paul’s theology integrates history and ontology. The exaltation of Jesus (Phil. 2:9–11) reveals his preexistent divine identity, while the worship of Jesus demonstrates his inclusion within the unique divine identity of YHWH. This theological understanding is grounded in the historical reality of Jesus’ life, death, resurrection, and ascension.

In1 Chron. 29:20, while the assembly bows (kamptō) to both YHWH and the king, the narrative and theological context make a critical distinction between the two. The bowing to the king reflects honor and submission appropriate to his office as YHWH’s anointed representative. However, the worship (proskynēsis) directed to YHWH is unique and transcendent, indicating divine reverence. The parallel physical gesture (kamptō) does not equate the king with YHWH but reflects the king’s subordinate role under YHWH’s ultimate authority. The bowing of every knee in Phil. 2:10 is explicitly linked to Isa. 45:23, where YHWH alone declares, “To me every knee shall bow, every tongue shall swear allegiance.” In Isaiah, this act of bowing signifies universal submission and worship reserved exclusively for YHWH. By applying this prophecy to Jesus, Paul affirms that Jesus is included within the divine identity, not merely honored as a human representative or agent of YHWH. The context is universal and eschatological, emphasizing the worship of Jesus as divine. The worship in 1 Chron. 29:20 is local and limited to Israel’s assembly, whereas the worship in Phil. 2:10–11 is universal—“in heaven, on earth, and under the earth.” Such universal worship transcends the honor given to any human king and aligns with the monotheistic worship reserved for God alone in Jewish thought.

The Macedonians “gave themselves first to the Lord” (2 Cor. 8:5) in a context of worshipful devotion, offering their lives and resources in service to God. While they also dedicated themselves to the apostles, the two acts are not identical. The self-giving to the apostles follows their submission to God and is framed as a response to God’s will. This hierarchy reflects the apostles’ role as representatives of God, not as equals to Him. Dedication (heautous edōkan) to God is qualitatively distinct from dedication to human beings. The latter is conditional and functional (e.g., support of ministry), while the former is absolute and involves worship, reverence, and complete trust in the divine. This distinction underscores the unique status of God as the ultimate object of devotion. In Phil. 2:10–11, the universal bowing of the knee and confession of Jesus as Lord go far beyond the kind of dedication described in 2 Cor. 8:5. The act of every creature bowing to Jesus reflects the fulfillment of Isa. 45:23 and signifies divine worship, not mere submission or dedication.

The OT frequently differentiates between the honor shown to human figures (e.g., kings, prophets) and the worship due to YHWH alone. For example, proskynēsis directed toward kings or others is contextually limited to their role as representatives of YHWH and never implies divine status (e.g., 2 Sam. 14:4, 1 Sam. 24:8). Acts of worship directed toward YHWH (e.g., Exod. 20:3-5) are absolute and involve a level of devotion that cannot be transferred to any creature without committing idolatry. In Phil. 2, the act of bowing the knee and confessing Jesus as Lord is not confined to a local or limited context but involves every being in heaven, on earth, and under the earth. This universal scope reflects divine worship and cannot be equated with the limited honor given to kings or prophets in the OT. Rev. 5:13–14 reinforces this point, where the Lamb (Jesus) and the One seated on the throne (the Father) are worshiped together by every creature. This universal worship explicitly includes Jesus within the divine identity and reflects the NT’s consistent portrayal of Jesus as fully divine.

The Adam-Christ typology in Phil. 2 is widely supported by Pauline scholarship and aligns with the thematic contrast in Phil. 2. Adam grasped at equality with God (Genesis 3:5), leading to his fall, while Christ, who already possessed equality with God (Phil. 2:6), voluntarily humbled himself by taking on human nature (Phil. 2:7). This humility leads to his exaltation and universal worship. The hubris of the Prince of Tyre (Ezekiel 28:2) represents an anti-typology of arrogance and rebellion against God. While the Prince of Tyre exalts himself illegitimately, Christ’s exaltation is the result of his voluntary humility and obedience to the Father. The contrast between the two figures underscores Christ’s unique role as the obedient, divine Son, not a mere ruler aspiring to divine status. Phil. 2:6 explicitly states that Christ existed in the “morphē of God,” affirming his preexistent divine nature. This divine status is further emphasized in the universal worship of Jesus in Phil. 2:10–11, which mirrors the worship of YHWH in Isa. 45:23.

Recent comments