Biblical faith is almost always forward-looking. It is as much about what may or may not happen in the future as it is about the knowledge and experience of the God of Israel in the here and now. It is, therefore, almost always either fearful or hopeful.

Abraham hoped that he would become the father of many nations (cf. Rom. 14:18). Moses led the people out of Egypt in hope of reaching the land promised to their fathers, though many feared—for good reason—that they would never get there. Israel hoped to have a powerful king, who would unite them, judge them, and lead them out to fight against their enemies (1 Sam. 8:19-20). As religious, moral, and political leadership failed, they began to fear the wrath of God. The exilic community hoped for a return to the land and restoration of Jerusalem, for a renewal of priesthood and kingship.

When restoration fell short of expectations and new oppressors arrived on the scene, the fear of war, destruction, and scattering again drove a movement of repentance and inspired startling hopes of salvation. Jesus led a small community of disciples down a difficult path of painful but joyous witness to a coming transformation. The Jews, by and large, kept their hopes fixed on Moses (cf. Jn. 5:45), but out of the trauma of this “judgment” a new covenant existence, according to the Spirit and not according to the Law, was beginning to take shape. Envoys were sent out to explain the long-term consequences of these events to the nations of the Greek-Roman world.

So from Jesus’ inaugural declaration that the kingdom of God was at hand (Mk. 1:14-15) through to the closing testimony of John on Patmos that the Lord Jesus was coming soon (Rev. 22:20) the New Testament is a thoroughly forward-looking, fearful-hopeful, assemblage of documents.

What I propose to do here is set out the New Testament hope in greater detail, simply by sorting the bulk of the references to “hope” into a coherent narrative, and then ask how we may translate that narrative into something that has meaning for the church today.

Not much hope in the Gospels

The first point to make is that the “hope” word group (elpis, elpizō) is rare in the Gospels. The Jews, as already noted, set their hope on Moses (Jn. 5:45). The two disciples on the road to Emmaus had hoped that Jesus was the one to redeem Israel, but it had not worked out that way (Lk. 24:21).

Perhaps the Gospels are not really about hope. Discuss.

The one positive statement of “hope” actually looks beyond the “first horizon” of the war against Rome and the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. Matthew depicts Jesus in Isaianic terms as the servant of YHWH, empowered by the Spirit, who would “proclaim judgment to the nations,” and in whose “name the nations will hope” (Matt. 12:21; cf. Is. 42:1-4 LXX).

Hope in a coming rule of Jesus Christ over the nations

Here we have, indeed, the essence of Paul’s message—the good news that he was intent on proclaiming across the empire, from Jerusalem to Spain (Rom. 15:19, 24). Christ became a servant to Israel in order to ensure that the promises made to the patriarchs did not fail (Rom. 15:8). His death opened up a future—a better future—for God’s people beyond the destruction of war. As a result many Gentiles were celebrating the goodness and mercy of YHWH towards his people, and were even beginning to believe that one day this “root of Jesse” would rule the nations (archein ethnōn) too. As Isaiah had said (according to the Greek translators): “in him will the nations hope” (Rom. 15:12; cf. Is. 42:4 LXX).

In other words, they were hoping for a new “king of kings” or emperor, who would have the stature and function of an Artaxerxes, who boasted that he has “governed many nations (pollōn ethnōn arxas) and obtained the dominions of all the habitable earth (oikoumenēs)” (Jos. Ant. 11:216). Or of an Alexander, who “gathered a very powerful force and ruled over countries, nations and tyrants, and they became tributary to him” (1 Macc. 1:4). The difference, of course, is that this was a just and righteous king, who would rule at the right hand of the only living God, and whose reign would last throughout the ages.

It was Paul’s far-sighted conviction that eventually Christ would rule over the many nations of the oikoumenē. When Gentiles came to faith in Jesus, it was faith not simply in Jesus as a person, or even as a saviour, but in this future political realignment of the Greek-Roman world. So when he prays, “May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that by the power of the Holy Spirit you may abound in hope” (Rom 15:13), this is what he has in mind. He prays that they will hold to their hope of régime change, a new political-religious order.

The hope of being part of the new political-religious order

This narrative about the future rule of Israel’s God, through his Son, over the nations of the Greek-Roman world lies behind other expressions of hope in the apostolic writings. First comes the hope that Jesus would rule over the nations. Then comes the hope of inheriting or participating in that new state of affairs.

Paul speaks of himself and other Jews (I suspect) who were “the first to hope in Christ”—that is, they hoped for a future inheritance. This was the hope to which they had been called (Eph. 1:11-14, 18; 4:4). The Gentiles formerly had no such hope of participation in God’s new future (Eph. 2:12; cf. 1 Thess. 4:13).

The “hope laid up for you in heaven” (Col. 1:5) is also, in the final analysis, a hope for a new political-religious system, in which rule in heaven and rule on earth have been reconciled. This was the good news being proclaimed by the emissaries of the Jesus revolution to every creature under heaven (Col. 1:15-20, 23). The “hope of glory” was the hope of sharing in the public glory, renown, praise, etc., that Jesus Christ would receive from all peoples when his rule over the oikoumenē was established (Col. 1:27).

The Thessalonian believers, having renounced the worship of idols, had a steadfast hope that Jesus would deliver them from the wrath that would come on the pagan world (1 Thess. 1:3, 9-10). This was what it meant to put on as a “helmet the hope of salvation” (1 Thess. 5:8). Paul’s personal hope, as an apostle, was that he would be in a position to boast on that day because the churches had persevered in their witness to the coming rule of Christ over the nations (1 Thess. 2:19).

Timothy is told to train himself in godliness because it “holds promise for the present life and also for the life to come” (1 Tim. 4:8). The apostles were working hard towards this outcome because they had their “hope set on the living God, who is the Savior of all people, especially of those who believe” (1 Tim. 4:10). The eschatological frame of the hope becomes clear at the end of the letter. At the end of this present age “our Lord Jesus Christ” would be revealed as the “blessed and only sovereign, the king of kings and lord of lords” (1 Tim. 6:15, 17).

We find a similar argument in Titus 2:11-13. The grace of God has appeared, bringing salvation for all people, not for the Jews only. Those who believed in God’s new future were being trained in godliness in the present age, as they waited for the “blessed hope and manifestation of the glory of our great God and Savior, which is Jesus Christ” (Tit. 2:13, my translation, which reflects my view that “Jesus Christ” is in apposition to “glory,” not to “our great God and Savior”—Jesus is the glory of God).

Those who suffer have a hope of glory

Finally, there is the deeply felt hope that those who suffered and lost their lives in the “tribulation” that would accompany the transition from the old pagan age to a new Christ-honouring age would not miss out on the vindication and glory.

In the first place, this is the “hope of resurrection of the dead,” which Paul shared with the Pharisees (Acts 23:6; 24:15; 26:6-7; 28:20)—the second temple Jewish belief that when YHWH overthrew the oppressor and restored his people, many of Israel’s dead would be raised, some to everlasting life, others to everlasting shame (cf. Dan. 12:2).

Paul’s argument about suffering, endurance, character, hope, and the glory of God belongs to this narrative (eg. Rom. 5:2-5). Those being conformed to the image of the suffering Jesus naturally hoped for the redemption of their bodies and waited “for it with patience” (Rom. 8:24-25). Even the inanimate creature hope to be liberated from the futility of idolatry (Rom. 8:20-21).

They rejoiced in hope, therefore they were patient in tribulation and blessed those who persecuted them (Rom. 12:12-14). They had hope when they were reproached—vilified, accused—because Christ had suffered in the same way. As it was written, “The reproaches of those who reproached you fell on me” (Rom. 15:3-4; cf. Ps. 69:9). The hope of those who faced suffering and death because of Christ was not directed towards this life only; they would be made alive in Christ at the parousia (1 Cor. 15:16-22). The hope of the apostles was to be transformed into the image of Christ’s glory by sharing in his sufferings (2 Cor. 3:12-18).

The conviction that the oikoumenē to come would be subjected to the Son, who was “begotten” as king on the day of his resurrection, is firmly asserted at the beginning of the letter to the Hebrews (Heb. 1:1-2:9). But just as the salvation of Israel was achieved through suffering, so too witness to the oikoumenē to come would attract violent opposition. These Hebrew believers in the future rule of Christ over the nations would be glorified as “sons” on the same grounds that Jesus was glorified, through suffering and death, and Jesus would not be “ashamed to call them brothers” (Heb. 2:10-11; cf. Rom. 8:18-30).

The “hope” of these believers, therefore, was to be the future house of God over which Jesus was faithful “as a Son” (Heb. 3:6; cf. 6:11). They could confidently hold to this hope, even in the face of hostility, because Jesus had suffered and had been raised before them, and had entered into the metaphorical sanctuary in heaven to function as a high priest—after the order of Melchizedek, and therefore a king—on their behalf (Heb. 6:17-20). So the author urges them to “hold fast the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who promised is faithful” (Heb. 10:23).

When Peter says that his readers have been “born again to a living hope… to an inheritance that is imperishable, undefiled, and unfading, kept in heaven for you” (1 Pet. 1:4), many will think that he is speaking about eternal life in heaven with God after death. This is not the case. As everywhere in the New Testament, the hope is directed towards a future day, following “various trials” and much Christ-like suffering (1 Pet. 1:6; cf. 4:12-13), when Jesus Christ would be revealed to the world as judge of the nations, their exile would be brought to an end, and they would share in the glory that would be publicly ascribed to their Lord (1 Pet. 1:13, 17; 2:12; 4:5; 5:1, 4, 6, 10). This was a hope concerning the future status in the world of both the heavenly Christ and the earthly people of God.

Be careful what you hope for

What can we learn from this rather narrowly focused investigation at a time of mounting alarm about the state of the world and what the future holds? Perhaps the church worldwide will flourish for some time to come, but, at risk of sounding like an unreconstructed Western colonialist, it seems to me that at the cutting edge of global consciousness the witness of the church is being badly abraded. In all respects, we are desperately in need of hope these days. Here, then, are some concluding thoughts.

- I do not think that we should be hoping for a renewal of Christ’s rule over the nations. Christendom has come and gone. History does not repeat itself. The world won’t make that mistake again.

- The Bible does not appear to “hope” for a new heavens and new earth. The prospect of a final justice and vindication is clearly important theologically, but hope is directed towards things that happen in history.

- The church should be both fearful and hopeful about its life and mission in the coming decades. The mighty American evangelical church is tearing itself apart. The Anglican Church is worried about “the sustainability of many local churches,” as it loses 20% of regular worshippers during the pandemic. And I was listening this morning to a group of church leaders expressing their concerns about the impact of lockdown on the vitality of their congregations. I think that we are entering a new epoch. As Pope Francis said a few years back (I picked this up this morning, too), “we are not living in an era of change but a change of era.” Our fundamental hope must be that God is with us in this destabilising transition and will redeem us through it.

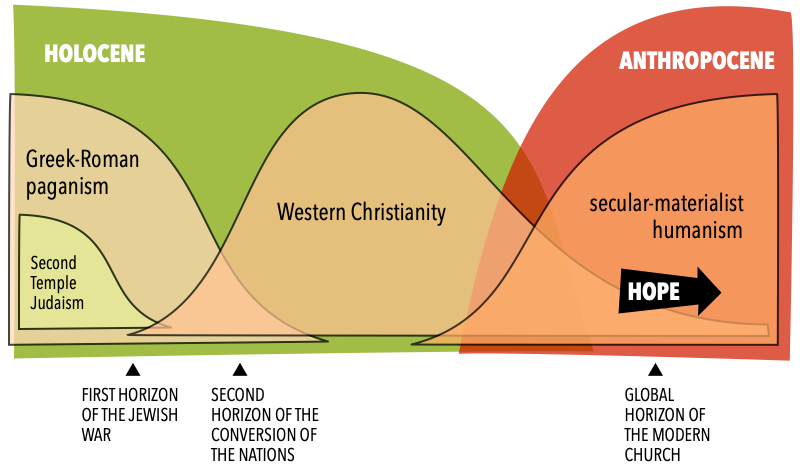

- I don’t think we will get the importance of hope for the church today—at least, the Western church—until we grasp the implications of this reworked graphic representation of the story of Western Christianity, overlaid on the epochal shift from the Holocene to the Anthropocene. It suggests, on the one hand, that Christianity has no historical right to survive; and on the other, that the future presents some immense challenges to the surviving church as a priestly and prophetic people.

- The question then is whether, in times of global crisis, the post-Christian world will find hope in the abiding presence in its midst of a re-formed, resilient, trustworthy, independent, prophetic, and priestly people of the only living God. That remains to be seen.

This is a really helpful article.

I’m probably not as aware as I should be of voices globally, but at least in America, I’d say one thing we’re missing is prophets. I should say, actual prophets that fit the role they played in the eschatological sights of the people of God in days past. We have plenty of prophets pointing people to QAnon or whatever.

Recent comments