I have spent way too much time finding fault with Matthew Bates’ argument that Paul alludes to the pre-existence of Jesus in Romans 1:3. Now to get on with the substance of Gospel Allegiance: What Faith in Jesus Misses for Salvation in Christ. It might be a bit ambitious to take this one chapter at a time, but let’s at least begin with the crucial first chapter on the gospel.

First, Bates says, there are certain things that the gospel is not. It is not a label that we can stick on any vaguely Christian activity to give it credibility. It is not social action. It is not a marketing slogan. It is not the Romans Road: “If the Bible’s own description of the gospel is the standard, the Romans Road entirely misses most of the gospel’s true content—and it adds many ideas that aren’t part of the gospel at all.” It is not justification by faith: the gospel is a statement about Christ, not about the means of my salvation. And if that’s not bad enough, the gospel is not exactly the cross.

In the Ancient Greek-speaking world the euangelizō word group was used for the public proclamation of good news. The euangelion was the content of that proclamation. In the New Testament it is the stark and simple assertion that Jesus is the Christ, the King.

The gospel according to Jesus

The “gospel of God”, according to Jesus, is that the “time has been fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has drawn near” (Mk. 1:14-15). Therefore, Jesus is “both the primary herald of the gospel and its principal subject” (42).

So the good news is that Jesus was anointed as the future king at his baptism and will soon begin to “rule officially on God’s behalf”.

His “royal manifesto” is set out in the words of Isaiah 61:1-2. It is thus “inherently political and social”. It is good news for the poor, prisoners, the blind, and the oppressed. Some of the benefits are available immediately; others “pertain to ultimate salvation in a future era that he is in the process of inaugurating” (44). Then pretty much everything that he does and says supports this gospel programme.

The gospel according to Paul

Bates begins his account of Paul’s gospel, a little surprisingly, with 2 Timothy 2:8: “remember Jesus the Christ, raised from among the dead ones, of the seed of David, according to my gospel” (46). What we learn from this is that Jesus is “the Messiah, the long-awaited Jewish (but universally significant) king; he was raised from the dead; and this good news is a matter of “royal prophecy”. No mention is made of the cross or of forgiveness of sins. An excellent observation.

Much the same story emerges from Paul’s summary of his gospel in Romans 1:3-4. God has promised to “bring about good news for his damaged creatures and indeed for the whole created order” (50). The Son of God has “come into being” in the flesh—this is the part of the argument that I think is unhelpful. He now reigns as heavenly king because of his resurrection from the dead. So the “principal gospel fact is that Jesus has become the absolutely sovereign king of the universe” (54). “The gospel is a royal proclamation”.

Again, there is no mention of the traditional gospel truths:

No human sin, God’s righteous standard, cross, death for sins, or return of Jesus. Nothing about heaven. Nor is the gospel said to be purposed toward helping a person get there. In fact, nothing has been said about our salvation at all. There is no mention of trust, repentance, or the like as part of the gospel. Neither is there any indication that justification by faith is part of the gospel. (55)

Excellent, but from my blinkered perspective…

The central contention that the “gospel” in the New Testament is not the offer of forgiveness of sins on the basis of the atoning death of Jesus but a public proclamation about the kingship of Jesus is put forward in a lucid and concise fashion. At the general level I think that Bates is right, and I’m hoping that he will take us a good way in the direction of working out the implications of what ought to be a revolutionary insight for modern evangelicalism.

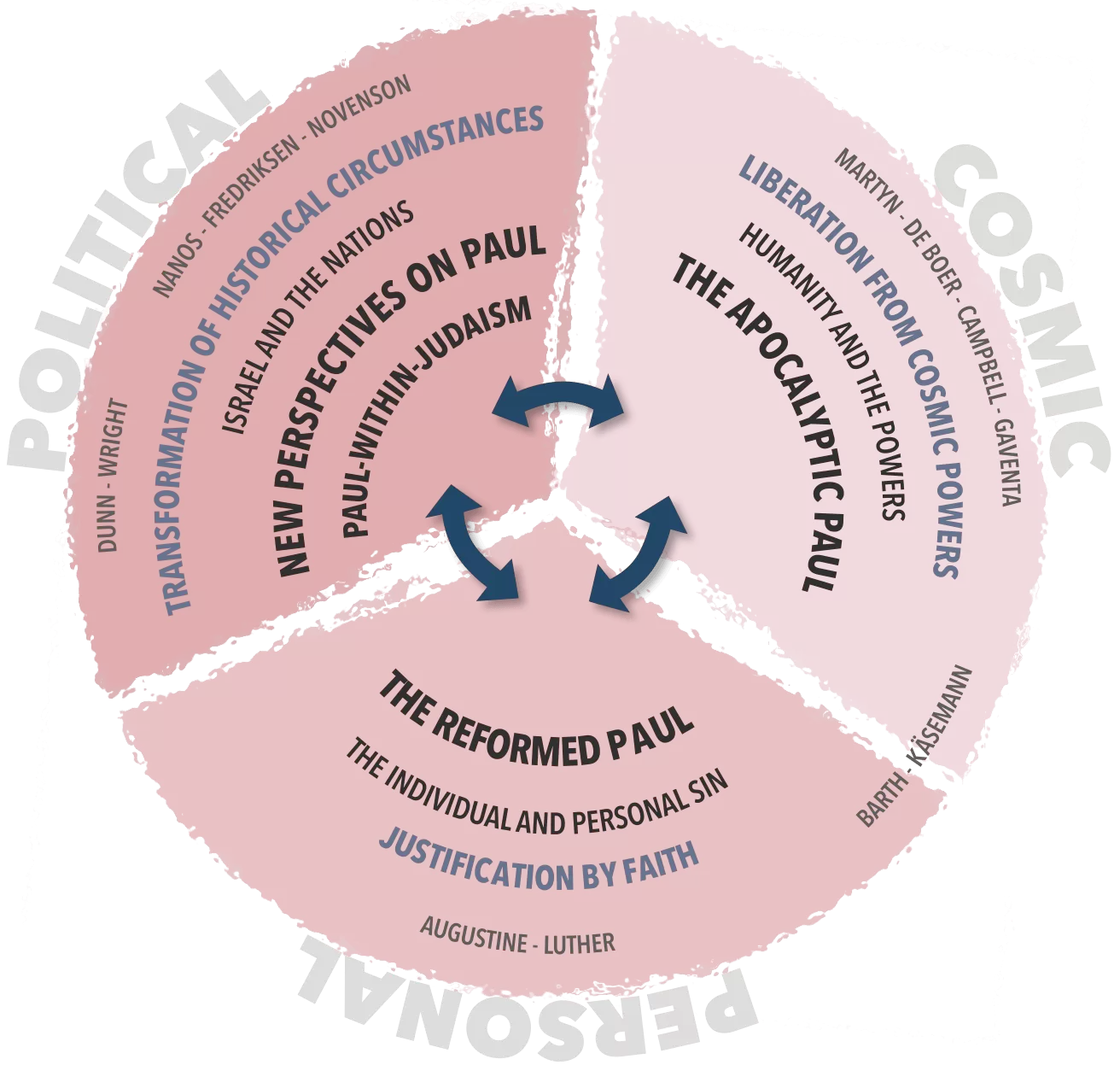

However, from a narrative-historical point of view—at least, from my narrative-historical point of view—the proposition has some shortcomings, perhaps inevitably given the laudable overall aim of providing a viable and religiously “thick” alternative to the conservative-Reformed gospel of “pastor-scholars like Matt Chandler, Greg Gilbert, John MacArthur, John Piper, and R. C. Sproul” (31).

My basic critique would be that this account of the Jesus is King gospel overshoots the essentially political-historical objectives of the mission of Jesus and the apostles.

So a few specific points of disagreement…

- When Jesus says that the “gospel of God” is that the “kingdom of God” is at hand, he is not speaking about himself. He is speaking about God. The good news for Israel was that God was about to act to put things right. He would judge and destroy the unrighteous; he would vindicate the righteous; and he would install Jesus at his right hand, along with his companions, as Israel’s messiah, Lord and King.

- The catastrophic “judgment” of AD 70, which I think dominates Jesus’ prophetic horizon and which is precisely why good news was needed, doesn’t get a look in. There is only passing reference to the Olivet Discourse to illustrate the theme of the “completion of time” (42). In Bates’ reconstruction there is only a final judgment at the end of history.

- Bates correctly highlights the political and social implications of Jesus’ reading from Isaiah 61:1-2, but then he seems to miss the political and social point: it is the liberation and restoration of oppressed Israel that is at issue. I don’t think that Jesus promises any gospel benefits that need to be deferred

- I don’t think that the baptism of Jesus is an anointing as king, as Bates maintains. I think it is an anointing as the servant-Son, who is Isaiah and ideal Jacob, who is sent to the mismanaged vineyard of Israel to demand the fruit of righteousness.

- This also seems to me to be mistaken: “Jesus was the righteous suffering servant, the king who represented his people as a substitute” (46). The servant of Isaiah 52:13-53:12 is not a king, and it is as a servant that Jesus believed his death would be a ransom for many (Mk. 10:45). Jesus becomes king by the power of the Spirit (here is the point of correspondence with the anointing of David) at his resurrection (cf. Rom. 1:4). First servanthood to the point of death (cf. Phil. 2:7-8), then kingship.

- Paul does not say that Jesus has become “sovereign king of the universe” (54). That function would be reserved for God the Father. Jesus has been seated at the right hand of God as the future judge and ruler of the nations (cf. Rom. 15:12). He is a political king, not a cosmic king. Likewise, to say that Jesus is “the universal Jewish-style king” presupposes a much later perspective. As far as Paul was concerned, Jesus was a Jewish king, not a Jewish-style king. When the last enemy has been destroyed and it is no longer necessary to rule over a people in the midst of the nations, the kingdom is returned to God the Father, so that the creator may be all in all (1 Cor. 15:24-28).

Recent comments