Chapter two of Matthew Bates’ Gospel Allegiance: What Faith in Jesus Misses for Salvation in Christ sets out his understanding of the Greek word pistis. In the first part he explains why he thinks that “allegiance” is a better translation of the word than “faith”. In the second part he asks how “allegiance” saves people. I’ll just look at the first part here.

The argument of chapter one was that mainstream conservative-Reformed pastor-theologians have quite seriously misrepresented the gospel. The gospel is not that Jesus died for my sins but that Jesus is king.

If that is correct, however, we also need to reconsider what faith is. The popular view, held by both believers and sceptical critics, is that Christian faith is belief in something for which we have no evidence. But the English words “faith” and “belief”, Bates argues, do not adequately express the meaning of the Greek word pistis. He thinks that the “best, most holistic term we can use to describe faith… when speaking about a saving response to the gospel” is the word “allegiance” (61). If the gospel is the good news that “Jesus now rules as the forgiving king”, then the appropriate response is loyalty to him.

Of course, you can offer allegiance to someone for whose existence you have no evidence, but that isn’t where we are going with this.

It’s not all about allegiance, but it is really

Bates is careful to say that pistis does not always mean “allegiance”:

My point is that the Greek word pistis has a meaning potential that can be actualized in different ways in context. One such way is allegiance. In fact, trust in or faithfulness toward a leader that endures through trials over the course of time is probably best termed “loyalty” or “allegiance.” But this is not to say that pistis or the related verb pisteuō consistently intend allegiance. They do not. (64)

I suspect that this comes in response to criticism about his previous book Salvation By Allegiance Alone. So he registers some instances where pistis means, quite conventionally, “trust” or “assurance” or “belief” (64-66).

The argument then takes a rather ambitious neuro-linguistic detour. Brain science tells us that most words have a “single prototypical meaning”. For Paul the basic sense of pistis would have been “trustworthiness (faithfulness) or trust (faith)” (67). But the term carries different nuances depending on the “social frame” within which it is used. So when we are speaking about a person’s response to a king, a “royal frame” is operative, and so “allegiance” is the “obvious actualization for pistis” (68).

I’m not sure that we need the brain science to tell us that meaning arises at the intersection of the general and the particular. That aside, I think that there are two basic problems with the thesis. First, do the texts that Bates puts forward as evidence really require the meaning “allegiance” for pistis? Secondly, is a “social frame” the right way to frame pistis in the New Testament?

Do the texts support the thesis?

Bates puts forward a number of texts, mostly from the New Testament, in support of his claim that pistis can mean “allegiance”. He says that there are more, but presumably these are the ones which he believes best illustrate the point.

- In 2 Thessalonians 1:4 pistis is associated with “steadfastness” in the face of persecution and affliction. Bates rightly points out that this will be the criterion for judgment when the Lord is revealed from heaven to take “vengeance on those who do not know God and on those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus” (1:8). But Paul goes on to say that when the Lord comes, he will be ”marvelled at among all who have believed (pisteusasin), because our testimony to you was believed (episteuthē)” (2 Thess. 1:10). Here pistis is a matter not of allegiance to Christ as king but of “belief” in the testimony of the apostles. What divides the believers from the non-believers in this argument is something that precedes the giving or withholding of allegiance: it is belief in the apostolic proclamation about the coming intervention of God as king to judge the pagan nations (cf. 2 Thess. 1:5).

- Paul speaks of “rejoicing to see your good order and the firmness of your pisteōs in Christ” (Col 2:5). Bates argues that pistis is here a matter of conduct, so it means “allegiance”. The faith of the Colossians in Christ, however, has just been explained. Its content is the word of God, the mystery that has now been revealed to the saints, “which is Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Col. 1:25-27). Further, they are to be “rooted and built up in him and established in the pistis“ (Col. 2:7). What makes this a matter of such urgency is that the wrath of God is coming on the world; therefore, they must set their minds on the future manifestation of Christ to the world, when they “also will appear with him in glory” (Col. 3:1-6). In Colossians 2:12 the object of their pistis is “the powerful working of God”, who raised Jesus from the dead. The apocalyptic narrative controls the argument. What Christ means to these saints and believing (pistois) brothers (Col. 1:2) is that he will be the archetype for their salvation when the wrath of God comes: they will suffer as he suffered, they will be glorified as he was glorified. That is their faith.

- The Philippian jailer first had to believe that the name of Jesus was powerful, then to put his trust in him personally, which would be expressed as an act of allegiance to his new Lord. What had got Paul and Silas in prison in the first place was the exorcism of the slave girl “in the name of Jesus Christ” (Acts 16:18). The earthquake was not something done in the name of Jesus; it was a simple act of God; so the jailer also rejoices along with his household, “having believed in the God” (pepisteukōs tōi theōi) who had done this marvellous thing (Acts 16:34). Context does not demand that the salvation of the jailer involved “an embodied switch in the jailer’s loyalty, no longer to the emperor’s magistrates but now to Jesus as the ultimate sovereign” (63). The pistis is only that such things are done by the power of God in the name of Jesus.

- In the examples from Josephus and 1 Maccabees it seems to me that pistis means “faithfulness” or “reliability” rather than specifically “allegiance”. King Antiochus believes that on account of their piety the Jews can be trusted with the property and land that he proposes to give to them (Jos. Ant. 12.147-52). King Demetrius urges the Jews to “persist in keeping faith (pistin) with us”, but this has reference to a friendship between nations on the basis of “agreements” (synthēkas) (1 Macc. 10:25-28). The Jews have not sworn allegiance to Demetrius, but they have remained “faithful” to the relationship established by the treaties.

- Jesus says to the church in Pergamum, “you hold fast my name, and you did not deny my faith even in the days of Antipas my faithful witness, who was killed among you, where Satan dwells” (Rev. 2:13). Later there is a call for the “endurance of the saints, those who keep the commandments of God and their faith in Jesus” (Rev. 14:12). Bates suggests that in these contexts pistis is best understood as “faithfulness or allegiance to Jesus the king” (64). But the denial of pistis is the antithesis to “you hold fast my name”, so this is probably the “faith” or “confidence” of believers such as “faithful” (pistos) Antipas in the power of the name of Jesus—as in the story of the Philippian jailer. The saying is similar to Revelation 3:8: “you have kept my word and have not denied my name” (Rev 3:8). There is again a prominent eschatological dimension to this faith: they are to hold fast to Jesus’ name, keep his word, not deny his name or their faith in him, because he is coming soon as judge (Rev. 2:16; 3:11).

So loyalty to Christ is no doubt in the background of the New Testament passages as an implication of pistis, but it is not what pistis signifies. Here we get to the question about framing.

The obedience of pistis among the nations

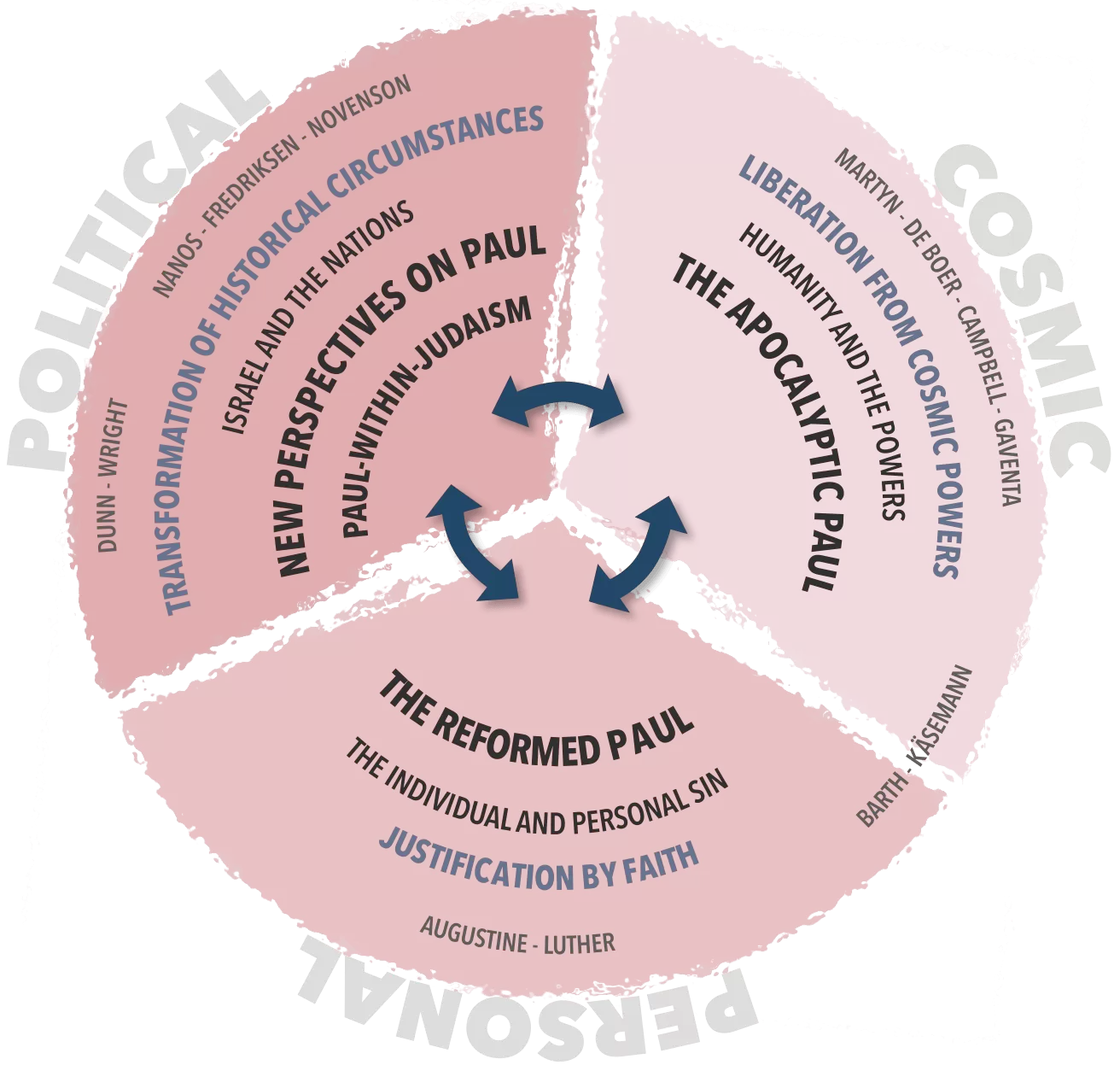

The problem with the argument about contextual meaning is that only the social or relational framing of the word pistis is considered. What Bates rather downplays—more or less disregards—is the apocalyptic dimension to pistis in the New Testament.

Faith was not merely directed towards Jesus as King or Lord, in which case “allegiance” might be a somewhat adequate translation. It was directed towards a highly improbable future outcome: that Israel’s crucified messiah would one day act as judge and ruler of the nations.

For that outcome to be achieved the churches would have to remain loyal to their Lord, but I don’t think that pistis is usually invoked for that purpose. What pistis signifies is the belief or faith or confidence or conviction of the first century churches across the oikoumenē that these things would indeed come about. Faith is what kicks off the prophetic, communal witness of the churches, which must bear witness in advance and over time, by their very existence, to a radically new political-religious future.

The oversight can be demonstrated from the discussion of the purpose of the gospel. Bates quotes Paul’s words at the end of Romans:

…my gospel and the preaching of Jesus Christ, according to the revelation of the mystery that was kept secret for long ages but has now been disclosed and through the prophetic writings has been made known to all nations, according to the command of the eternal God, to bring about the obedience of faith. (Rom 16:25–26)

He suggests that the phrase “obedience of faith” (hypakoēn pisteōs) should be translated “allegiant obedience” (71). The argument, however, is rather flimsy: since this is faith with respect to a Jewish king, pistis is likely to be a matter of allegiance. There is little consideration of context. The parallel with Romans 1:5 is noted: Paul’s task as an apostle was to “bring about the obedience of faith for the sake of his name among all the nations” (Rom. 1:5). Brief consideration is also given to Romans 15:15-16, but only to repeat the assertion that “the aim of Paul’s gospel proclamation is allegiance” (72).

I think we need to look at Paul’s argument in this passage much more closely.

His readers, he says, are to behave as Christ behaved (Rom. 15:2-3). Christ became a servant to Israel for two reasons: to confirm the promises made to the patriarchs, and to elicit worship of the God of Israel from the Gentiles. The Old Testament quotations illustrate the second purpose: the Gentiles praise YHWH because he has acted faithfully towards his people. But the sequence culminates in the declaration that the root of Jesse will rule over the nations (Rom. 15:12; cf. Is. 11:10). Here is Paul’s gospel again: the one who was a descendant of David according to the flesh is now the Son at the right hand of God who will eventually be confessed as Lord by the nations of the pagan oikoumenē. In this future king the Gentiles hope.

So Paul prays: “May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing (en tōi pisteuein), so that by the power of the Holy Spirit you may abound in hope” (Rom. 15:13). This is crucial. The hope is in the future rule of Christ over the nations, and Paul prays that God will give them joy and peace as they believe in this.

Paul then goes on to explain why he has written to them. There are a few things that need straightening out, he says. His task as a “minister of Christ Jesus” is to ensure that the “offering of the Gentiles may be acceptable, sanctified by the Holy Spirit” (Rom. 15:16). Therefore, Christ has been working through him to “bring the Gentiles to obedience—by word and deed, by the power of signs and wonders, by the power of the Spirit of God” (Rom. 15:18–19).

There is no reference to pistis, but it is clearly of a piece with Romans 1:5 and 16:26. When he speaks of the “obedience of faith” of Gentile believers, the pistisis in the future rule of Christ: it is a matter of conviction about an eschatological outcome.

So yes, I think that Bates is right at a general level to foreground allegiance: the faith of the early churches had to be lived out as steadfast loyalty to their risen Lord, often in the face of intense opposition, always to the exclusion of other supreme loyalties.

I think this makes a credible and sustainable break with the old salvationist paradigm and should be inspirational for the church today. But it misses what I think is the all-important, apocalyptically conceived narrative frame of the New Testament gospel.

Theologians generally, whether salvationist or “allegiantist”, are much more comfortable with a synchronically expressed “faith” in Jesus. New Testament faith, however, is overwhelmingly diachronic in its orientation—futurist, apocalyptic, eschatological.

Jews and Gentiles across the oikoumenē came to believe 1) that Jesus had been raised from the dead and exalted to the right hand of God, and 2) that he would eventually be acknowledged as king by the nations. This pistis was certainly expressed as allegiance to Christ as Lord, but it emerged in the first place as belief in the testimony of the apostles, underpinned by signs and wonders and the direct experience of the Spirit of God, and the conviction or “hope” that the God of Israel would sooner or later overthrow the old pagan order. It was by their faith in this outcome that first century believers would be justified.

An afterthought

I suppose that if we think the apocalyptic outlook that controlled New Testament thought is not relevant for faith today, we could flip the diagram around, consigning apocalyptic to history and living in an eternal present. It’s not my view, but it would alleviate the tensions between Bates’ largely synchronic account of faith as allegiance to Christ as king and the aggressively diachronic New Testament paradigm.

This pistis was certainly expressed as allegiance to Christ as Lord, but it emerged in the first place as belief in the testimony of the apostles, underpinned by signs and wonders and the direct experience of the Spirit of God, and the conviction or “hope” that the God of Israel would sooner or later overthrow the old pagan order.

This seems very relevant for today along with its attendant missional and ethical implications.

Two questions (one from each world):

1. I can imagine Gentiles also sharing this hope, particularly if they were disillusioned by world created by the pagan order. But we’ve observed a rather early drift into more cosomological interests by the Greco-Roman early church fathers. Do you have any guesses as to how that happened? Pro-Roman sentiment? A general level of comfort with the pagan world?

It’s easy to imagine Gentiles struggling with some of these ideas without the Jewish context, but assuming the gospel preached to them was this same hope that Jesus would rule over the nations, I wonder what began to make that facet less important in light of things like immortality, afterlife, and the cosmic battle of good and evil.

2. We are at a stage in history with our own struggles that, at least at a principial level, have some similarities. We also have to have faith that our impending crises will not have the last word in what God is doing for the world and His people. In the New Testament, believers responded with prophetic proclamation, ethics conditioned for their particular historical situation, instructions due to a foreseen crisis, etc.

Where, if anywhere, is this kind of thing happening, today? It seems like it should be.

@Phil L.:

1. I can’t answer that question off the top of my head. The loss of interest in apocalyptic began very early. There’s no apocalyptic discourse in John’s Gospel. The action in the temple is where John’s story starts, not where it finishes. The destruction of the temple is more a metaphor for Jesus’ death than a historical reality. It’s also a pretty attenuated presence in the Early Church Fathers.

Perhaps part of the problem is that, whereas the gospel begins in Jerusalem as part of a high level, politicised debate about the future of Israel as a nation, it inevitably becomes more diffuse, less focused, as it spreads across the empire. Other debates come into play and begin to set the agenda.

2. Agreed. I rather think that the church in Europe is more acutely aware of historical change than the church in America.

There’s a good Afterword by Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, to the book This Is Not A Drill: An Extinction Rebellion Handbook. He writes:

In the Book of Proverbs, in the Hebrew Scriptures, the divine wisdom is described as ‘filled with delight’ at the entire world which flows from that wisdom. For me as a religious believer, the denial or corruption of that delight is like spitting in the face of the life-giving Word who is to be met in all things and all people. I long for and pray for change, not just because I want to see my children and their children having a planet to live on, a future that will not be marked by a rising spiral of violent conflict over what is left of the world’s goods and a downward spiral of disadvantage and deprivation for the most vulnerable. I long and pray for it because here and now we need to recover our health, our balance—the skill of living with and in the neighbourhood that is this world.

It doesn’t say everything, but enough of these brief out-breathings may become a wind of prophecy as we go through the death-throes of an old age.

@Andrew Perriman:

Thanks, Andrew. That was a great passage from Williams.

Recent comments