Paul Fromont (one of two prodigal but thoughtful Kiwis) has kindly highlighted my The New Testament and “what now for the church” post, in which I nailed my colours to the mast regarding the formative potential of a narrative-historical reading of the New Testament. I mentioned in the post that I like Tom Wright’s five act play analogy for biblical authority but disagree about how the story that is told in this divine meta-comedy is to be reconstructed. Paul asked about this.

Andrew…, how about a post on why you disagree with Tom Wright on how the New Testament narrative is reconstructed? … I’m reading though that you’re in agreement with his analogy of an unfolding drama in five-acts…? I’ve always found it a really useful analogy.

Yes, it is a useful analogy. It gets away from the Bible-is-authoritative-because-it-says-so approach, and it brings into the foreground—stage front, if you like—the concrete, intentional, creative response of the biblical community. So far, so good.

My main disagreement with Wright here is that, in his view of things, history more or less grinds to a halt when we get to Paul. Wright recognizes the framing importance of the impending judgment on Israel for determining the nature of Jesus’ mission. But when we get to Paul, we have basically arrived at a general-purpose Christianity—admittedly not quite Christianity as traditionally conceived—and theology no longer engages with history as narrative. Theology disengages from the particularities of history and binds itself instead to human universals.

I would argue, to the contrary, that the impending clash between the emerging churches and Rome was as important for Paul’s theology as AD 70 was for Jesus’ theology. New Testament theology is at every point, retrospectively and prospectively, an engagement with history.

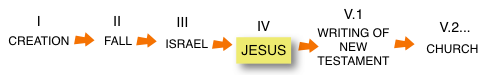

In The New Testament and the People of God Wright sets out the first four acts according to a classic theology of redemption. The writing of the New Testament forms the first scene of Act V, giving hints (Romans 8, 1 Corinthians 15, parts of Revelation) about “how the play is supposed to end”.

The church would then live under the ‘authority’ of the extant story, being required to offer an improvisatory performance of the final act, as it leads up to and anticipates the intended conclusion. (142)

The church takes its narrative bearings from the first four acts and the eschatologically framed hope that God will ultimately make all things new. It looks like this:

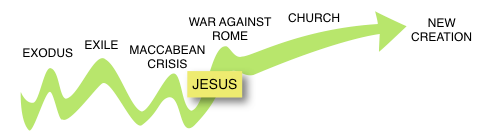

It seems to me, though, that Wright’s historical—rather than theological—reconstruction of the narrative of Jesus and Israel would look more like this (omitting creation and fall only for the sake of simplicity):

Between the historical events of the exile and the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 Jesus re-establishes the reign of God over his people through his death and resurrection, thus bringing Israel’s history to its climax and inaugurating the fifth act of the church.

Jesus believed it was his vocation to bring Israel’s history to its climax. Paul believed that Jesus had succeeded in that aim. Paul believed, in consequence of that belief and as part of his own special vocation, that he was himself now called to announce to the whole world that Israel’s history had been brought to its climax in that way. When Paul announced ‘the gospel’ to the Gentile world, therefore, he was deliberately and consciously implementing the achievement if Jesus…. He was calling the world to allegiance to its rightful Lord, the Jewish Messiah now exalted as the Jewish Messiah was always supposed to be. A new mystery religion, focused on a mythical ‘lord’, would not have threatened anyone in the Greek or Roman world. ‘Another king’, the human Jesus whose claims cut directly across those of Caesar, did.1

I think, however, that it makes better sense both of the Old Testament and of the New Testament to say that the climax to Israel’s story comes historically with the defeat of pagan empire, the international confession of Israel’s messiah as Lord, and the inheritance of the nations by the descendants of Abraham. This was entirely dependent on the preceding event of Jesus’ death and resurrection; it was dependent on Paul’s proclamation of the ecumenical significance of that event to the nations; it was dependent also on the existence of a faithful community that lived out the prophetic significance of Jesus’ death and resurrection in the pagan world.

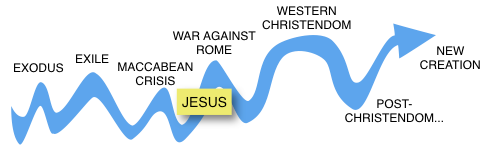

But history does not stop when we get to Paul’s articulation of the significance of what God was doing through Jesus for the sake of the future of his people. So I think it is misleading to suggest that following the writing of the New Testament we have less than one act still to live out.

I would say that the period from the events of the New Testament to the conversion of Rome should constitute a separate act—the outworking of the conviction generated in the New Testament that the people of God would “inherit” the Greek-Roman world. That would be the rest of act five, perhaps—the story of how the family of Abraham went from “exile” to “empire”.

But then the period of Western Christendom should also constitute a theologically significant act as the socio-political expression of the victory of Christ over the pagan nations. Most of the history of the church, directly or indirectly, has been the story of Christian political, cultural and intellectual imperialism. But this sixth act has also come to an end… and so it goes on.

The theological engagement with history continues—and I think that we have to recognize that there is going to be a lot more to it than just finishing off a fifth act. The church still suffers from an intellectual complacency engendered by the Christendom experience. We have barely begun to take account of the challenges that lie ahead. I do not question the authority of scripture in this. But I think that by consistently and coherntly reconstructing the narrative-historical shape of New Testament theology, we put ourselves in a much better position to deal theologically with the complex crises of the post-Christendom, post-modern church.

- 1Tom Wright, What St Paul Really Said (Oxford: Lion Publishing, 1997), 181.

A couple things popped into my head while reading this. First was that the "victory of Christ over the pagan nations" feels more like the co-opting of Jesus by empire than a victory. And the second was the church's mission to the rest of the known world(Persian Empire and beyond) should also be included in the story(good resource: http://www.aina.org/books/bftc/bftc.htm).

The questions I have follow from them. Can we really treat Christendom as a victory? Do we think that Paul would have thought it was the victory he anticipated? And if we do include the church of the east missions in the story, does that effect our telling of it at all?

Recent comments