In Jesus and Divine Christology, Brant Pitre argues that Jesus walking on water (Matt. 14:22-33, Mk. 6:45-52, Jn. 6:16-21) reveals his divine nature. He highlights two points: first, the act reflects God’s power as in Job 9:8, where only God walks on the sea. Second, Jesus’ statement “I am” mirrors God’s self-identification to Moses. However, the story’s context emphasizes the disciples’ failure to understand Jesus’ messianic role, linked to the feeding miracles and their hardened hearts. The narrative frames Jesus as Israel’s deliverer, akin to Moses, leading his people through trials, embodying God’s saving presence.

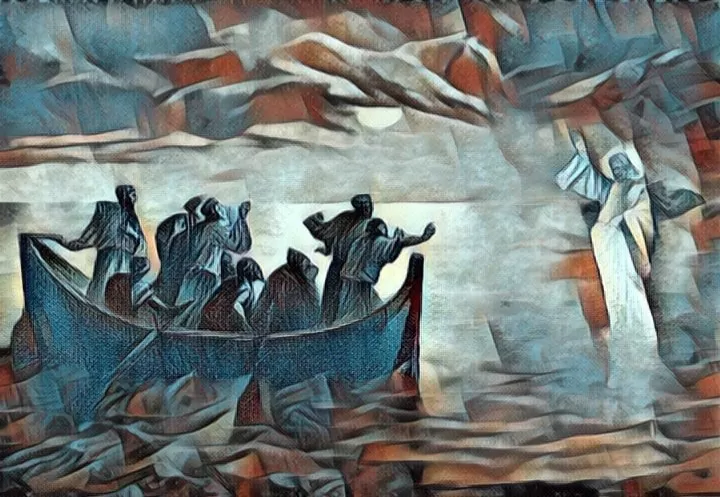

The second “epiphany miracle” discussed by Brant Pitre in his book Jesus and Divine Christology is Jesus walking on the water (Matt. 14:22-33; Mk. 6:45-52; Jn. 6:16-21).

The disciples are making slow progress across the Sea of Galilee against a strong headwind. In the early morning, according to Mark, Jesus “comes toward them walking on the sea.” He wants to “come alongside (parelthein) them” (Mk. 6:48*), but the disciples think that they are seeing a “ghost” (phantasma) and are terrified. Jesus reassures them immediately: “Have courage, I am (egō eimi); do not be afraid” (6:50*); and he gets into the boat.

The two main arguments for thinking that the miracle of Jesus walking on the water is an epiphany of his divine nature have been widely rehearsed in the scholarly literature.

Only the “I am” walks on the sea

First, it is clearly stated in scripture that it is God who “alone stretched out the sky and walks (peripatōn) on sea as on ground” (Job 9:8 LXX*).

Pitre does not mention this, but Job goes on to say: “If he passed over me, I would not see; and if he passed by (parelthēi) me, I would not know” (9:11*). Jesus “meant to pass by them,” according to some translations. I think it makes much better narrative sense if we translate parelthein in the Gospel story as “pass alongside”—cf. Lk. 12:37; 17:7, where it has the sense of coming among a group reclining to eat. Jesus intended to come directly alongside or among them, but they were terrified, so he had first to reassure them that it is he.

Pitre concludes: “When we interpret Jesus’s act of walking on the sea in the light of Jewish Scripture, a strong case can be made that it is epiphanic: that is, it reveals that Jesus is equal in divine power to the Creator” (70).

Secondly, Pitre has “three good reasons” for thinking that Jesus’ “I am” means more than just “It’s me.”

1. The absolute form of the expression “echoes the divine self-designation given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai” (71-72).

2. The conjunction of “I am” and “do not fear” is found in “two of the most exalted and decidedly monotheistic descriptions of the one God of Israel in all of Jewish Scripture”:

But now thus says the Lord God, he who made you, O Jacob, he who formed you, O Israel: Do not fear, for I have redeemed you; I have called you by your name; you are mine. (Is. 43:1 LXX)

Be my witnesses; I too am a witness, says the Lord God, and the servant whom I have chosen so that you may know and believe and understand that I am. Before me there was no other god, nor shall there be any after me. (Is. 43:10 LXX)

I am, I am the one who blots out your acts of lawlessness, and I will not remember them at all. (Is. 43:25 LXX)

Thus says the Lord God who made you and who formed you from the womb: You will still be helped; do not fear, O Jacob my servant and the beloved Israel whom I have chosen… (Is. 44:2 LXX)

3. Jesus says, “I am; do not fear,” while he is walking on the sea. So “interpreters who insist that Jesus is merely identifying himself fail to take seriously the extraordinary context in which he uses this particular self-designation” (73).

This background cannot be entirely dismissed, but I think the divine epiphany argument misses the point of the story.

It’s all about the loaves, stupid!

By stupid I mean “you stupid disciples,” not “you stupid modern interpreters.” Nevertheless, I will say this, with respect. Pitre repeatedly stresses the need to understand these stories in their first century Jewish context, against the background of Jewish scripture, but he seems to pay scant attention to the immediate literary context in the Gospels. There is much in the story that he conveniently overlooks, its narrative framing to begin with.

Jesus’ name has become known to Herod. There are rumours that John the Baptist has been raised from the dead, that Elijah has come, or that Jesus is a prophet “as one of the prophets.” Herod leans towards the John the Baptist theory (Mk. 6:14-16*).

Jesus takes the apostles away to a quiet place after their mission trip, but the crowds follow, and he has compassion on them because they are as “sheep without a shepherd” (6:34). This casts Jesus as the successor to Moses who will lead the people so that “the congregation of the LORD may not be as sheep that have no shepherd” (Num. 27:16–17), or as the Davidic king who will feed the scattered sheep of Israel and be their shepherd once God has rescued them and judged their enemies (Ezek. 34:20-24).

The themes of the abundance of loaves and the obtuseness of the disciples then recur through the narrative until we get to Peter’s decisive confession in the region of Caesarea Philippi.

Jesus immediately compels the disciples to get into the boat and set off without him to the other side of the Sea of Galilee (Mk. 6:45), and at the end of the pericope they are astounded because “they did not understand about the loaves, but their hearts were hardened” (6:52*). The account of Jesus walking on the water is tightly linked to the loaves theme.

After a second mass feeding, this time in foreign territory, Jesus again withdraws hastily across the sea (8:10), and the disciples again fail to grasp the meaning of the over-abundance of bread. They do not perceive or understand, their hearts are hardened, their eyes do not see, their ears do not hear (8:14-21). They are not so different from uncomprehending Israel, to whom a prophet has been sent to speak in parables (4:10-12).

But then a blind man is healed in stages in Bethsaida (8:22-26), and so we come to the critical question, put to the slow-witted disciples: “Who do you say that I am?” Not John the Baptist, not Elijah, not one of the prophets. For Peter the penny finally drops; he has grasped the significance of the compassionate feeding of the scattered sheep of Israel: “You are the Christ” (8:29); and then Jesus must explain to his disciples that the Christ is the Son of Man who must first suffer many things.

So I think we must first ask how the walking on the water episode fits into the narrative of the disciples’ slow realisation that Jesus is the one who attends to the needs of the congregation of Israel—the successor to Moses, the Davidic shepherd of Israel. After all, that there is a connection can hardly be denied: the disciples are greatly amazed by the sea miracle because they did not understand about the loaves, but their hearts were hardened (6:52).

In this respect, if “I am” carries any christological freight at all, it must be understood as a self-identification as Israel’s leader and deliverer. Before the crossing of the sea, the people “fear” (ephobēthēsan) the Egyptians, and Moses says, “Be courageous (tharseite), stand, and see the salvation from God, which he will do for you today” (Exod. 14:13 LXX*). The people then cross the sea walking on dry ground. The crossing of the lake is a lose re-enactment of the crossing of the Red Sea.

If there are secondary connotations of God himself walking on the water, that is because the saving hand of God is seen in the action of the leader: “Israel saw the great hand, what the Lord did to the Egyptians; and the people feared the Lord and had faith in God and Moses, his servant” (Exod. 14:31*).

The reaction of the disciples

Pitre thinks it supports his case that the disciples are “terrified” when they see Jesus—“the ordinary human reaction to a theophany or appearance of God” (70). But as far as Mark and Matthew are concerned, this is the ordinary human reaction to seeing a ghost (Matt. 14:26; Mk. 6:49-50). It makes nonsense of the story, frankly, to suppose that they are terrified that it might be a ghost and Jesus then calms their fears by hinting at his divinity.

We also must reckon with Matthew’s expansion of the story. He has Peter try to pull off the same trick and he nearly drowns (Matt. 14:28-31). As with the stories of the failure of the disciples to still the storm or heal the epileptic boy, Jesus accuses him of being “of little faith” (oligopiste). This is a nature miracle that the disciples should have been able to replicate, at least in Matthew’s view.

Pitre also does not mention the disciples’ response to the extraordinary events in Matthew: they prostrate themselves before Jesus and declare, “Truly, you are (a) son of God” (Matt. 14:33*). This is not such an exceptional confession.

The absolute “I am”

According to Pitre, the absolute form of “I am,” without a predicate, must be an allusion to the divine “I am,” at least as it appears in the Isaiah passages. The grammatical form, however, is by no means exceptional.

- In Matthew’s version, Peter seems to take Jesus’ “I am” as a simple self-identification in response to their fear that this was a phantasm: “Lord, if you are (sy ei), command me to come to you on the waters” (Matt. 14:28). He says this because he is persuaded that Jesus is not an apparition but a solid human person like himself. He would hardly volunteer if he thought that only God walked on the water.

- When Jesus says that one of them will betray him, the disciples ask, “Am I (egō eimi), Lord” (Matt. 26:22*). The predicate is easily omitted: they don’t say, “Am I the betrayer?” or “Am I he?”

- Jesus replies to the high priest’s question, “I am, and you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the cloud of heaven” (Mk. 14:62). The predicate is presupposed from the question (“the Christ, the Son of the Blessed”), but if “I am” has intrinsic christological significance, the response underlines the association with the messianic motif.

- False messiahs will come in Jesus’ name, saying, “I am” and “The time is at hand” (Lk. 21:8). A false messiah says, “I am,” because a true messiah says, “I am.”

- When the Samaritan woman asks if Jesus is the Christ, he says, “I am—the one speaking to you” (Jn. 4:26).

- In John’s version of the walking on the sea story, when Jesus says, “It is I; do not be afraid,” the disciples are just happy to take him into the boat (Jn. 6:20). It’s hard to read an epiphany into that.

- The healed blind man ‘was saying, “I am”’ (Jn. 9:9). No predicate there.

- Jesus tells the disciples about the coming betrayal so that when it happens, they may “believe that I am.” But he then says, “whoever receives me receives the one who sent me” (Jn. 13:19-20). Jesus is the “I am” sent, not the “I am” who does the sending.

So there is quite a bit of evidence here to suggest that to the extent that the absolute form is remarkable, it is a way of identifying the messiah.

In the Isaiah passage referenced by Pitre, YHWH speaks to his servant Jacob: I have redeemed you, I have called you by name, I have chosen you, you are my beloved; therefore, the servant Jacob should not be afraid; YHWH is with them when they pass through water (Is. 43:2); he is the one “who provides a way in the sea, a path in the mighty water” (Is. 43:16 LXX).

The Exodus motif is prominent here, but also Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels is naturally identified with the beloved servant whom YHWH has chosen (Mk. 1:11; cf. Is. 42:1). So where the symbolic pathways intersect, we find Jesus the beloved servant, who is the successor to Moses, leading his people through the dangerous waters of a new exodus and a new exile.

As the obedient servant or Son, he perhaps may be said to “embody” or mediate the saving presence of Israel’s God to his followers who are “of little faith” and little understanding, but we should not over-assert this thought to the occlusion of the explicit and sustained messianic theme.

I am interested in your discussion as to how the story of walking on the water functions.

The discussion of whether this is to be taken as an expression of Divinity or as Messianic seems to me to miss the point Mark is making and both views smack of us trying to ask the narrative to answer our questions. (Despite this, I dont deny that there are obviously RESONANCES to one or the other.)

It seems to me that a true narrative reading would recognise the water, (actually the sea), for what it is in Mark, namely the narrative “character” which expresses the divide between the Israelite and “the other”. This also seems to be the narrative purpose in Mark of the two feeding stories. One for Israel, and the other for “the others”. Elizabeth Struthers Malbon has been fairly eloquent as a scholar of this view.

If this is true, then the narrative functions not as a discussion of Divinity v Messiahship, but rather a narrative seeking to explore the universal mission of this Messiah/Divinity.

I suppose my question is this, “When will we stop asking and responding to our own (and others) questions of the text, and start to let the narrative structure of the text speak for itself?

@Richard Blakesley:

Richard, thanks. Yes, more could have been made of the sea crossing, though I’m not convinced it’s a journey from Israelite territory to “the other.” When they reach Gennesaret, he is immediately recognised by people (Mk. 6:54) and there is a dispute with Pharisees and scribes who have come from Jerusalem about the traditions (7:1-23). I would have thought the underlying issue here is still whether he has the authority to speak and act as he does.

We then go on an excursion through Tyre and Sidon, where Jesus begrudgingly heals the daughter of the Syrophoenician woman, and back to Decapolis for the second feeding miracle. This foreign territory but it seems to me likely that the 4,000 are mostly Jews, representing Jews of the diaspora (5 loaves + 7 loaves = 12 loaves?), with perhaps some Gentiles coming “from far away” (8:3).

The narrative is not a discussion of divinity versus messiahship, agreed—Mark would not have seen these as antithetical. But I don’t think we can play down the identity issue in these chapters: who is this who has such authority? He is the Son of Man who has authority on earth to forgive sins, he is the prophet like Moses who will take his people on a second exodus, he is the Davidide who will feed scattered Israel in the wilderness, he the Christ, the Son of God, and so on.

@Andrew Perriman:

Thanks Andrew for your reply.

I think you have convinced me that there is something of an identity issue here more than i had allowed for.

Recent comments