Douglas Moo’s interpretation of Paul’s theology in Romans centers on a “salvation history” framework, where Christ’s death and resurrection mark the climax of history, dividing the old age of sin from the new age of righteousness. However, the critique argues that Moo’s focus on salvation as a personal faith experience neglects the broader “kingdom” theme in Paul’s writings, which emphasizes Jesus’ rule over nations as a historical, political event. This critique suggests that Paul’s perspective aligns more with Jewish apocalyptic views, taking history seriously rather than reducing it to individual salvation.

According to Douglas Moo, the theological or conceptual “framework within which Paul expresses his key ideas in Romans can be called salvation history” (D. Moo, The Epistle to the Romans, 1996, 25). What he means by this is that “God has accomplished redemption as part of a historical process. God’s work in Christ is the center of history, the point from which both past and future must be understood” (26). So the cross and resurrection of Jesus are, on the one hand, the fulfilment of the Old Testament, and on the other, they anticipate the “final glory”.

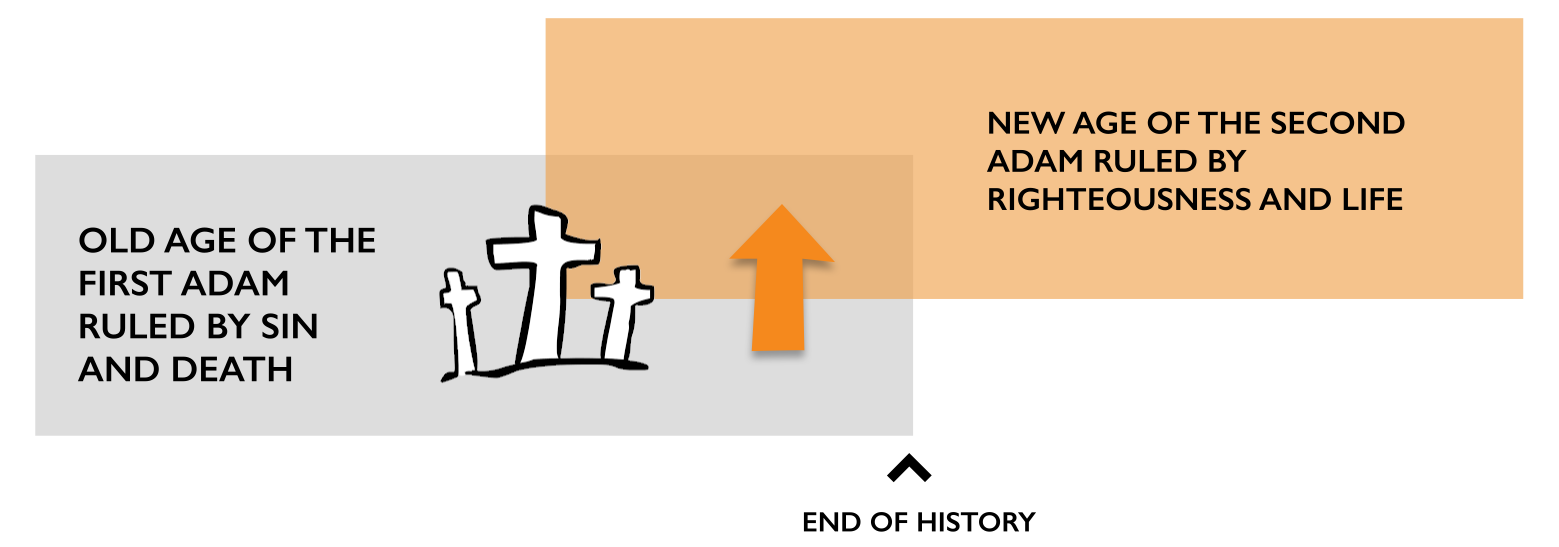

Christ is, therefore, the “climax” of history, dividing an old age of sin, law, flesh and death from a new age of righteousness, grace, Spirit and life. People are saved when they are transferred from the old age to the new.

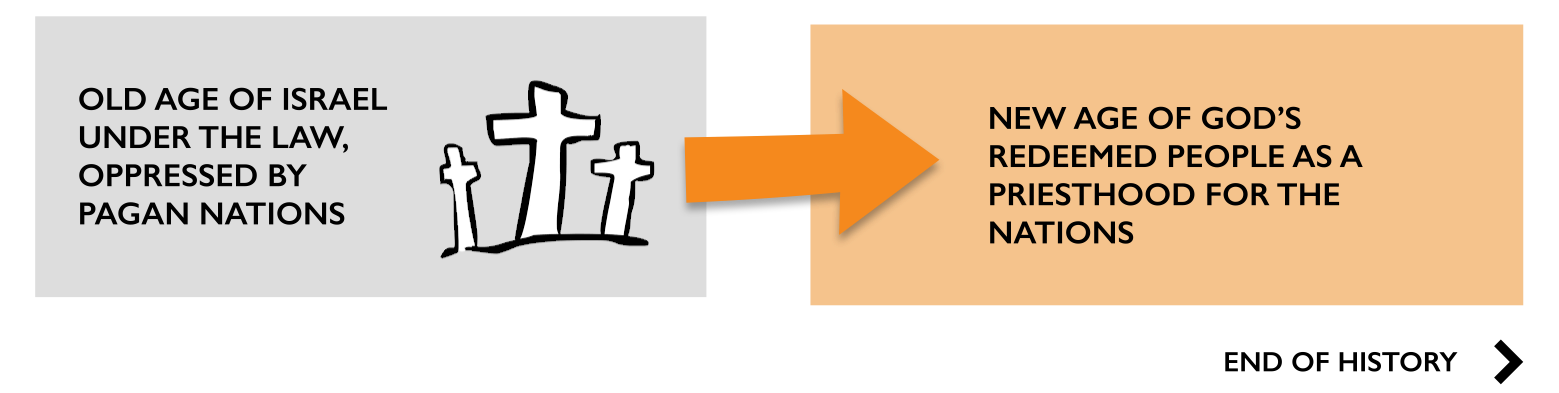

The two age schema is found in Jewish apocalyptic, Moo notes, but he thinks that Paul has modified it. Whereas Jewish apocalyptic expected the transition between the two ages to take place “in the field of actual history,” for Paul the new era has been inaugurated in history—redemption has been accomplished, the Spirit has been poured out—but will not be fulfilled until the end of history, when God’s kingdom is finally established.

Both ages exist simultaneously; and this means that “history,” in the sense of temporal sequence, is not ultimately determinative in Paul’s salvation-historical scheme (26).

So the “salvation” component of Moo’s “salvation-historical” schema is actuated not in history after all but in the faith of the individual believer: ‘the “change of aeons,” while occurring historically at the cross..., becomes real for the individual only at the point of faith’.

Moo’s commentary is now rather dated, but this way of understanding the overall “narrative” structure Paul’s thought has quite widespread currency. As I see it, there are two basic problems with Moo’s argument. Both parts of the salvation-historical construct are misconceived.

It’s all about kingdom

First, it is not salvation but kingdom or rule that should be determinative for the conceptual framework. Paul’s “gospel” in Romans is not that Jesus died to redeem humanity but that he has been “appointed Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord” (Rom. 1:4*). Paul’s task as an apostle is to bring about an obedience among the nations that accords with belief or faith in the future rule of the “root of Jesse” (1:5; 15:12).

If a descendant of David or “root of Jesse” becomes “Son of God in power,” that is a political development, which in all likelihood echoes Psalm 2—and Moo acknowledges as much (48):

I will tell of the decree: The LORD said to me, “You are my Son; today I have begotten you. Ask of me, and I will make the nations your heritage, and the ends of the earth your possession. You shall break them with a rod of iron and dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.” (Ps 2:7-9)

Redemption through the death of Jesus is a necessary corollary of this conviction, but it is not what drives the argument. The train of thought runs: Jesus will rule over the nations; therefore there must be wrath against the Greek; therefore there must be wrath against Israel; therefore a people needs to be saved in order to inherit the promises made to Abraham (4:3); therefore God has put Jesus forward as an expiation for the sins of Israel (3:25).

There is a “new creation” dimension to the transition because, as in the Old Testament, the inauguration of a new political-religious order is a powerfully re-creative event:

For as the new heavens and the new earth that I make shall remain before me, says the LORD, so shall your offspring and your name remain. From new moon to new moon, and from Sabbath to Sabbath, all flesh shall come to worship before me, declares the LORD. (Is. 66:22-23)

But the reality is better expressed in kingdom terms:

He has delivered us from the domain of darkness and transferred (metestēsen) us to the kingdom of his beloved Son… (Col. 1:13)

Here’s a parallel. With the assent of the Seleucid king Antiochus Epiphanes, the high priest Jason “immediately transferred (metestēse) his compatriots to the Greek way of life” (2 Macc. 4:10*). Just as Jews were put under pressure to adopt the cultural practices of the new political arrangement into which they were being transferred, so gentile believers in Colosse or Rome were required to adopt the radically different values and practices of the new kingdom into which they were being transferred.

But kingdom remains a way of managing the complexities, conflicts, corruption, and crises endemic in human societies. If there were no sin and death, there would be no need for kingdom, which is why, when the last oppressor of his people has been destroyed, Christ delivers the kingdom back to God the father (1 Cor. 15:24-25). He stops being king when new creation comes.

It’s all about kingdom until we get to the end

Secondly, Paul does not present kingdom or rule over the nations as an end-of-history event. Admittedly, we do not have much to go on in Romans, but he neither corrects the historical orientation of hopes found in the Jewish scriptures and apocalyptic writings nor affirms the sort of final eradication of sin and death that we see in Revelation 20:14; 21:1-4.

So it seems at least worth testing the hypothesis that Paul did indeed expect the transition between the two ages to play out over time, under normal historical conditions.

It’s interesting that Moo has to contrast the supposedly salvation-historical idea that the age to come is inaugurated in history with the Jewish apocalyptic notion that the transition from the old aeon to the new happens in the field of “actual history.”

It sounds like an admission that the traditional paradigm really has nothing to do with history. Apart from the fact that it had been prophesied in the Old Testament, the timing of Jesus’ arrival on the scene is arbitrary; it has nothing to do with the “actual” historical circumstances of first century Israel or diaspora Judaism. So Moo can easily re-centre what is happening on the personal faith of any individual person.

Jewish apocalyptic explains Paul better than the salvation-historical model

The conceptual framework of Romans, therefore, is closer to the outlook of Jewish apocalyptic; it takes history seriously and cannot be so easily reduced to the salvation experience of the individual believer.

Jewish apocalyptic was driven by the need for a solution to the historical crises faced by Israel in the Hellenistic-Roman era. Paul was convinced that the resurrection of Jesus from the dead and his elevation to the right hand of the Father was the solution that his people were looking for. Jesus was the anointed one who would judge not only his own people but also the immediate enemies of his people—the peoples of the Greek-Roman world who for so long had conspired against the Lord and his anointed (cf. Ps. 2:1-3). There is no reason to remove this narrative from the “field of actual history.”

Recent comments