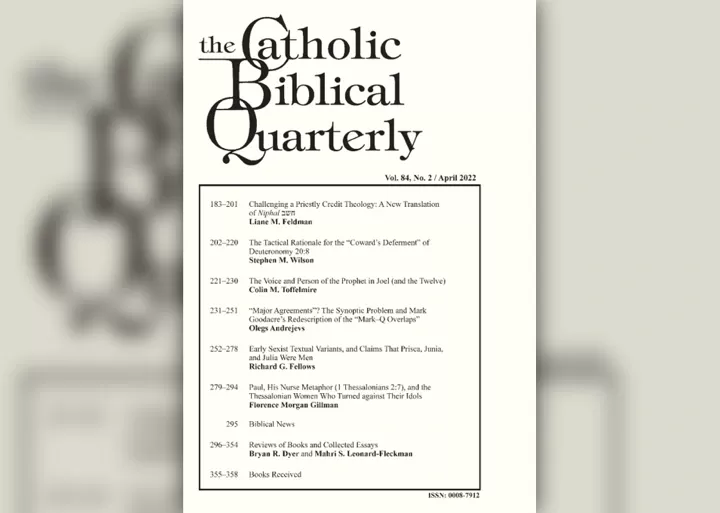

The current issue of the Catholic Biblical Quarterly includes my article “When the Fullness of the Time Came: Apocalyptic and Narrative Context in Galatians.” It’s only available to subscribers for the time being—and, of course, in libraries—but here’s the abstract and a brief overview of the argument with a couple of diagrams.

This article examines the two phrases “the fullness of the time” and “the present evil age,” found in Galatians, against the backdrop of Jewish apocalyptic chronologies of divine action and in relation to Paul’s argument about the interpolation of the law in the letter. Whereas interpretation and theological reflection tend to generalize the intervention of God as the ideal pivot of salvation history, I argue that in Paul’s mind the timing of the sending out of the Son is bound up with realistic perceptions of the condition of Israel and hopes for a transformed future. To the extent that the coming of “the fullness of the time” determined the end of the guardianship of the law, the moment is conceived not as a second exodus but as the final resolution of a tension that was inherent in the arrangement from the start.

This follows a standard hermeneutical procedure: the overblown metaphysical structures of popular theology are scaled down to the proportions of Israel’s history, which is unquestionably the controlling narrative of both the Old Testament and the New Testament. The benefits for the church are two-fold: we get a proper understanding of the historical seriousness of scripture; and we are propelled to take our own place in history such more seriously.

In theological perspective, Paul’s argument in Galatians the God sent his Son in the fullness of time to deliver us from the present evil age (Gal. 1:4; 4:4) is assumed to have reference to the whole of human experience. The “present evil age” began with the fall and will end in spectacular fashion with second coming, final judgment, kingdom of God, and new creation.

The sending of the Son is likely to be regarded as a sending from outside human experience in conformity with the standard incarnational paradigm. J. Louis Martyn—to give a less than standard example, in fact, but an influential one nevertheless—speaks of an “invasive act on God’s part.”

The phrase “the fullness of time” is found to denote some metaphysically pregnant, but otherwise arbitrary, moment in cosmic time. Francis Watson says that Paul’s gospel “announces a definitive, unsurpassable divine incursion into the world… that both establishes the new axis around which the entire world thereafter revolves and discloses the original meaning of the world as determined in the pretemporal counsel of God.”

In narrative-historical perspective, on the other hand, the largest narrative in view in Galatians is really the story of Israel, and for Paul’s polemical purposes it is the period of confinement under the Law, because of transgressions, that provides the temporal frame for what is said about Jesus.

In brief, I argue in the article that the “present evil age” is the period of internal turmoil and external oppression that has recently come upon Israel. Perhaps in Paul’s mind it would stretch back as far as the crisis provoked by Antiochus Epiphanes in the early second century BC, which had such a profound impact on the Jewish apocalyptic consciousness.

The expression “in the fullness of time” is, therefore, to be taken quite realistically. Jesus arrived on the scene as this political-religious crisis was building towards a disastrous climax, before it was too late to salvage anything from what would be, in historical terms, a “final” judgment on second temple Judaism. His mission was not to save the world but to “redeem those who were under the Law” and who could no longer save themselves from the catastrophe by keeping the Law.

So then, as I argue in a chapter in my book on the pre-existence of the exalted Christ, it makes no sense to speak of a sending or incursion of the Son from outside the world. The metaphysical conditions that might make such a dogma meaningful are simply not there. Instead, we have abundant evidence for the idea that a leader such as Moses or any of the prophets might be “sent out” (with exapostellō in the Septuagint, which is the word Paul uses) to Israel, at some critical moment in Israel’s history, to perform some critical task (e.g., Exod. 3:12; Ps. 104:26-27 LXX; Mic. 6:4; 2 Chron. 36:15-16; Jer. 1:7).

Thank you, Andrew. Somehow I missed this one when it was first posted.

re: “The expression “in the fullness of time” is, therefore, to be taken quite realistically. Jesus arrived on the scene as this political-religious crisis was building towards a disastrous climax, before it was too late to salvage anything from what would be, in historical terms, a “final” judgment on second temple Judaism.”

I think that Romans 5:6 must be relevant to this question; the timing of the sending of Jesus to Israel was not arbitrary. It also raises tantalizing questions of whom and what Paul had in mind in the phrase “while we were still powerless.”

Is there enough material to justify a book length treatment of “Atonement theory in narrative historical context?”

@Samuel Conner:

I agree about Romans 5:6. Paul is speaking on behalf of the Jews: while we Jews were still weak, Christ died for ungodly Israel. What he meant by “weak,” though, is less clear. I presume something like: Israel was too weak to deliver itself from its predicament.

I’ll have a think about the atonement theory suggestion. Thanks.

Recent comments