We have an online Communitas “Thinklings” event coming up this week, spread over a few days, to consider the question of church and mission after the pandemic. Brian McLaren helped us launch this informal theological forum nearly 20 years ago, and we’ve kept it going fitfully. Never before online though.

I picked up Is Europe Christian? by the French political scientist Olivier Roy to help set the scene. It was published last year, so it doesn’t take coronavirus or Black Lives Matter into account. But I think it may be helpful, as we consider the impact of these more recent developments, to remind ourselves of the larger historical context.

The first four chapters of the book cover the period up to the 1960s:

- an overview of Europe’s Christian heritage going back to the 11th century;

- the emergence of a secularised form of Christian culture from the 18th to the mid-20th century;

- the dispute between the Church and secular society over the source of the values that they held in common (faith or reason?);

- and the self-secularisation first of the mainline Protestant churches, then of the Catholic Church in the period leading up to Vatican II.

The secularisation of Christian Europe

The first part of the thesis, therefore, is that for much of the modern era European culture was a secularised version of its pre-modern Christian culture.

European Protestantism embraced secularisation quite readily, “both in terms of morals—the best of Christianity resides in ethics, which are universal—and in terms of theology—God reveals himself in the profane” (62). Schleiermacher, von Harnack, Bonhoeffer, and Harvey Cox are mentioned. The Catholic Church was much slower to come to terms with modernism, being concerned that the authority of the magisterium would be undermined.

But broadly speaking, while there was disagreement about the final grounds of morality (why certain behaviours are good and right and others bad and wrong), for a long time the churches and secular society shared the same spread of social-ethical values.

Ironically, the Catholic Church caught up with modernity, with the theological and liturgical reforms of Vatican II (1962-65), just as modernity was mutating spectacularly into something very different and very colourful. “The paradox is thus that just when the Church had accepted a secular civil society, the common values of society drifted away from those of the Church” (69).

That brings us to the cultural revolution of the 1960s.

The dechristianisation of secularised Christian Europe

The 1960s “witnessed the affirmation of a new anthropological paradigm” that shattered the common base of secularised religious values (72).

A wave of student-led movements swept the world between 1963 and 1973, much of it Marxist in character. In western Europe and the US, however, the cultural upheaval took the form of a swing towards a “libertarian neoliberalism,” expressed principally in the area of sexuality and family (73). The new values that emerged were progressively enshrined in law—most recently the legalisation of same-sex marriage—and are now dominant in European culture (76-80).

According to Roy, there are three main components to the “Sixties model.”

1. The valorization of individual freedom. “This was extended to the realm of desire, which became a standard in itself and was no longer subject to any constraint other than the desire of others” (74). The more recent #MeToo movement and outrage over paedophilia in the church are not a reversion to moral puritanism as much as “attempts to prevent desire from being used to justify power relations or predatory relationships.” Desire is good, but not when it serves male power.

2. The valorization of nature, in respect to both the environment and the individual’s body and instincts, as opposed to the “tradition of the free exploitation of nature, attributed to the capitalist system” and moralistic control of the body.

Sixties culture introduced a new relationship with nature, which is seen as intrinsically good without recourse to any norm (there is no ‘morality of nature’), and which is therefore malleable and can shift according to human will. (75)

3. The emphasis on “gender” as a socially constructed and therefore “fluid” category: “the very notion of gender allocation, whether biological or cultural, is being contested.” This has been demonstrated in the abolition of sex discrimination, the normalisation of same-sex relationships, and the more recent endorsement of the individual person’s right to determine “their” own gender identity according to desire.

The new natural

This whole transition can be understood, I think, as a redefinition or realignment of the natural order. What held the modern secularised-religious ethical consensus together prior to the 1960s was the belief that morality was grounded in a predetermined and unchangeable natural order, defined by the church theologically as “natural law” or by secularists as an intrinsic biological order, which said, for example, that the role of women was to bear and raise children and that homosexuality was unnatural and perverse.

What the sixties revolution introduced was the idea that it is the free, instinctual desire of the individual that discovers what is natural and therefore what is good and right. The new anthropology is rooted in a new understanding of nature essentially as how the world appears from the perspective of the individual liberated from the trammels of authoritarian religious and ethical tradition. If science supports this new perspective (for example, in showing that not all people are born straight or that sexual identity is “naturally” fluid), all well and good. But in any case personal human rights now take precedence over science.

Beleaguered minorities

This cultural earthquake immediately demolished the “shared base of secularized Christian values,” and after the 1960s the secularisation of Europe gave way to the dechristianisation of Europe.

In chapter six on the “religious secession” Roy outlines the Christian response to the sexual revolution.

Beginning with Humanae vitae the Catholic Church took a reactionary stance against the liberalisation of sexuality, defending a set of traditional values understood to be, in the words of Pope Benedict, “inscribed in human nature itself and therefore… common to all humanity” (82). Thus the Catholic Church seceded from the secularised-religious coalition, abandoning the process of aggiornamento or “updating” that had produced the reforms of Vatican II.

The secession “ushered in a new world in which faith communities are—and definitely believe themselves to be—beleaguered minorities” (84). Roy has in mind here primarily the Catholic Church because the major Protestant churches have continued their policy of self-secularisation; they have endeavoured to “integrate new paradigms into their theology, such as the ordination of gay ministers or religious services for gay marriages, which dilute them even more in secularized society” (86).

The Church’s “repositioning in favour of a militant, uncompromising religiosity” also effectively brought about the demise of Christian democracy in Europe (97-101). In effect, the Church gave up on broad-based political engagement in order to safeguard the set of core moral values directly threatened by the sexual revolution.

Under John Paul II and Benedict XVI, the Church embarked upon a new mode of political intervention, focusing on the non-negotiable moral issues (against abortion, euthanasia, same-sex marriage, artificial procreation) without proposing a comprehensive view of society. (99)

The globalising tendency of the church and the loss of social witness

The next part of Roy’s analysis brings into consideration the impact of what we might call “evangelical renewal” across the religious spectrum since the 1960s.

There has been a measure of charismatic or “tradismatic” revivalism in the Catholic Church, but these communities have been largely inward-looking, the outstanding exception being the Community of Sant’Egidio (86-96).

So the Church, on the one hand, has pared down social-political engagement to opposition to sexual liberation and, on the other, has pursued charismatic models of ministry that tend to circumvent or transcend concrete social experience.

Here we enter into one of the deep contradictions of the new ministry, for the universalism that characterises the charismatic movement in fact perfectly suits a church that has lost its sway over actual societies and then finds in a globalized world the idea space to regain its autonomy…. (100)

Both charismatic Catholicism and evangelical Protestantism confine their interest to nurturing a personal spiritual life in generalised or universal terms with little reference to people’s actual cultural and social circumstances, which are determined locally or regionally. The overall effect is that the church has largely abandoned the social arena.

Roy concludes his discussion of the religious secession from much of public life by asking a question that may be of some importance for mission in the European context:

But how can this universalism be reconciled with the desire for rootedness and inculturation, which alone are able to re-establish the link between the Church and a society that has lost faith? How can faith and identity be reconciled? (101)

The hermeneutics of it

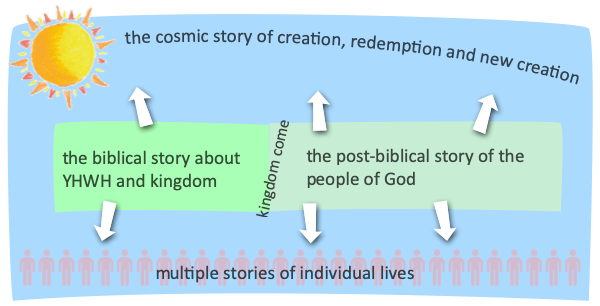

What I find interesting here is that this exactly matches my argument about evangelical hermeneutics, that theological attention oscillates between the overarching story about creation that makes redemption necessary and the narrow field of the personal response to the saving event. What generally gets overlooked is the yawning gulf of actual political history that lies between the personal and the cosmic and which actually dominates the biblical narrative.

The story of the kingdom of God is not an allegory of personal faith, nor is it an account of cosmic transformation. It is the story, fundamentally, of the God of Israel and the nations of the Greek-Roman world. It is a story, therefore, about Europe. It is the story, in fact, that directly gave rise to the tumultuous history of faith and identity, up to the present day, that Roy so concisely outlines.

A practical correlate of the narrative-historical hermeneutic, therefore, is that evangelical mission in Europe must have something constructive and substantive to say broadly about European social identity. Mission today should be commensurate with mission in the New Testament period, even if the conditions and plausible outcomes are very different.

Europe and the Other

The other major part to Roy’s analysis is the influx of migrants from the Muslim world and the populist recourse to Christian symbolism in order to defend a culturally homogeneous European identity.

He argues that there are two fronts in the culture wars in Western Europe and the US: the “internal front over values and the external front over immigration and Islam” (105). In the US these two fronts more or less coincide. In Europe they do not, and a more complex cultural war zone exists as a result.

Along the internal front over values are Christian conservatives, on one side, lined up against “secularists of all persuasions, liberals and populists alike.”

The external front between those who fear Islamization and those who welcome Muslim immigration runs at ninety degrees to the internal front, dividing both religious conservatives and secularists. He cites the example of Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, who “represents the most liberal wing of populism in terms of social mores, and the most repressive toward Islam, which he wants to outlaw outright” (110-11).

Again, Roy makes the point that in contrast to the US it is the Catholic Church in Europe that is leading the battle for traditional values. The mainline Protestant denominations have largely adopted the new values, while Protestant evangelicals avoid the public-political arena: “given that they position themselves as a global movement and that a large majority of their adherents come from immigrant backgrounds, the question of Europe’s identity is irrelevant to them” (107).

So the Church finds itself under assault from two directions.

The arrival of Islam in Europe has put the Church in an ambiguous position. It has powerfully “reintroduced religion into the public sphere,” but at the same time it “calls into question the continent’s Christian identity, and more importantly poses as a serious competitor for its spiritual reconquest” (112). So the aim of the church has been not to suppress Islam but to assert its own priority and seniority.

Roy goes on to argue in chapter eight that the growing presence of Islam in Europe is making life more difficult for the churches: “If Christianity’s place in society is shrinking, it is because, in addition to the broad trend of secularization, the urge to limit the role of Islam amounts to reducing the religious sphere in general” (149).

In relation to secularism, the Church has developed a “siege mentality,” made worse by the paedophilia scandals. It has no prospect of reconverting Europe and is, therefore, left with three courses of action.

1. There is the option of “political combat to enshrine Benedict XVI’s non-negotiable moral issues in law as much as possible” (115-16). The example of Ireland shows how unlikely this is to succeed.

2. There is Rod Dreher’s “Benedict option” of withdrawal into modern monasteries until a new era of faith dawns.

3. The third option is “spiritual reconquest” through preaching. Rather than looking backwards to preserve an old Christian identity, perhaps in a shallow and expedient alliance with populism (118-24), Christianity has to “rebuild itself,” start over again, “even at the price of our own deculturation” (117-18).

That’s interesting….

Some questions…

I’ve enjoyed this book, mainly because it makes us ask questions about Europe as a real place, with its own distinctive history, which in important respects is a biblical history. It is not just another bit of the planet where humans get saved by their faith in Jesus.

But I have some questions about where this leaves us, particularly as missionally minded evangelicals in Europe.

1. How important to the mission of an “evangelical” organisation like Communitas in the European context is the issue of social-cultural identity? Is it a reason for the very limited success of evangelical missions that we have been largely indifferent to what happens in the vast area of social-political controversy between the personal and the cosmic?

2. Part of my argument in End of Story? Same-Sex Relationships and the Narratives of Evangelical Mission is that the modern church does not share the ancient understanding of nature (thanks to science and the desacralisation of the world), and that to bear witness under present historical conditions to the realities of new creation, we are bound to find ways to accommodate, biblically and theologically, at least a version of the post-1960s anthropology. OK, so that tries to say too much in too small a space, but my question is whether we can get beyond the current theological confusion and develop a coherent alternative anthropology to underpin the social witness of the church.

3. Is there a way of usefully fusing the second and third of Roy’s three final options? Dreher’s neo-monasticism sounds too reactionary and isolationist, but monastic communities may have a more positive, socially engaged, prophetic function. Spiritual “reconquest” sounds at best over-ambitious and at worse neo-imperialist, but mission that comes by way of dying and deculturation can at least claim strong New Testament precedent.

4. Roy’s thesis takes account of pressures on the residual Christian presence in Europe from two main directions: sexual liberation as the driving force of dechristianisation and Islamic incursion. But over the last few months we have become acutely aware of two other forces destabilising the world as we know it, for better and for worse, though neither is entirely new. First, the Black Lives Matter movement has reminded us that patriarchy is not the only social justice issue demanding a fundamental reform of western cultures. Secondly, I think that the coronavirus pandemic, while serious enough in itself, has given us a vivid glimpse of just how disruptive a global climate emergency might be. How do these developments change our view of the future presence of the church in the European context? Do they bend the story in a different direction?

5. I want to close with a rather intriguing and unexplained quotation from the end of chapter eight:

If Europe is to become Christian again, it is in need of prophets, not legislators. But the prophets may very well turn out not to be where one expects to find them. (150)

I’m not sure what he means by that, but what might we want him to mean by that? It’s not really my call, but I don’t expect Europe to become Christian again. But I do think that the church in the secular, dechristianised West must be a prophetic community. What might be unexpected about that?

Recent comments