I want to begin the new year by exhorting “evangelicals”—that is, by my definition, Christians who think that the Bible is to be taken seriously—to get to grips with eschatology. Why not? It’s as good a time as any to pause and reflect on where things are going.

The traditional view is that the events associated with the coming of the Son of Man on the clouds have not yet happened—even though Jesus seemed confident that his parousia would take place within the lifetime of at least some of his followers (Matt. 16:28; 23:36; 24:34; Mk. 8:38; 9:1; 13:30; Lk. 9:27; 21:32). We are still waiting. I think we are waiting in vain. Worse than that, I suggest that by constantly deferring the “end” we are not engaging with the present, and for that reason we are missing the whole point of New Testament eschatology.

If the historical Jesus said that at the end of the age the Son of Man would send his angels and they would “gather out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all law-breakers, and throw them into the fiery furnace” (Matt. 13:41–42), his Jewish audience would have heard this as a statement about a coming judgment on Israel as it was at that moment—a deeply troubled and divided nation under Roman occupation.

Any reference to the kingdom of the Son of Man would naturally have evoked the complex analysis of Daniel 7-12. Israel was under intense pressure from an intrusive pagan power to abandon the ancestral religion. Many Jews apostatised, but the righteous were determined to remain true to the covenant and were subjected to severe persecution. The assurance given to Daniel in the vision of chapter 7 was that the aggressive pagan empire would be judged and rule over the nations formerly subject to it would be transferred to “one like a son of man”, who was (probably) a symbolic representation of the persecuted righteous. At the same time, many dead Jews would be raised—the righteous to everlasting life and glory, the apostate to shame and condemnation (Dan. 12:2-3).

Jesus took this story of crisis, judgment, vindication and kingdom out of its second century context and retold it, with some adjustment, for the benefit of a new audience. His message was that YHWH was about to act in a fashion similar to that envisaged by Daniel to judge the wicked and lawless in Israel, deliver his people from their enemies, and vindicate the suffering righteous—Jesus himself in the first place, but also his followers, to whom would be given the authority to judge and rule over Israel and perhaps also the nations currently subject to Rome.

This “end of the age” of second temple Judaism would not happen immediately, and there could be no certainty about the exact timing, but the historical Jesus was confident that within a generation the leadership of Israel would “see” the Son of Man coming with the clouds, not only vindicated by God but seated at the right hand of Power (Matt. 26:64; Mk. 14:62; Lk. 22:69).

The reaction of the high priest and the council makes it clear that they did not regard this as idle speculation about impossibly remote end-time events:

Then the high priest tore his robes and said, “He has uttered blasphemy. What further witnesses do we need? You have now heard his blasphemy. What is your judgment?” They answered, “He deserves death.” (Matt. 26:65–66)

They understood that Jesus was prophesying quite brazenly that, in a foreseeable future, under the prevailing political conditions, in a manner that would be publicly evident, the right to govern the people of God would be violently taken from them and given to him as the glorified Son of Man.

Jesus’ eschatology, in other words, was a direct engagement with history. He was doing what Jewish prophets had always done.

The same can be said, I think, for the eschatology of the early church as it took the good news about Israel’s crucified and risen messiah into the Greek-Roman world, right to the heart of the dangerous beast-like empire.

It was a quite outrageous but historically meaningful mission.

Through reflection on the Jewish scriptures, through visions and prophecies, in the ecstasy of worship, they became convinced that far more was entailed in the recent developments, far more was at stake, than the governance of Israel.

That the Son of Man was now seated at the right hand of Power meant that the centuries-old dominance of the pagan empires was at last coming to an end, as Daniel had foreseen; the old gods were going into exile (cf. Is. 46:1-2), though they might be expected to put up a fight; and the nations formerly subject to Rome would soon bow the knee to, and confess the name of, a new Lord, to the glory of the God of Israel (Phil. 2:9-11).

This is the thrust of what I think is one of the most misunderstood—but one of the most important—passages in the New Testament. Paul addresses a polite and rather conventional critique of pagan idolatry to the men of Athens in the Areopagus, but the climax to his speech is nothing short of revolutionary:

The times of ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all people everywhere to repent, because he has fixed a day on which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead. (Acts 17:30–31)

For both Jesus and the prophetic and apostolic churches, therefore, “eschatology” was a direct challenge to the political-religious status quo. The current tenants of the vineyard of Israel would be destroyed and the vineyard would be given to others (Mk. 12:9). The powers that dominated the Greek-Roman world, whether in the heavens, or on earth, or under the earth, would soon be overthrown and a new kingdom established.

The deferred eschatology of modern evangelicalism, however, is a pale, misplaced and unenlightening imitation of the intense apocalyptic visions that shape the thought of the New Testament. We keep putting it off because, really, we have no idea what it’s for, what it’s supposed to achieve, or how it might intersect with the solid, confident narratives of modernity.

I think this amounts to a failure of nerve on the part of the evangelical church. Here are three resolutions for the new year that will help to set things right.

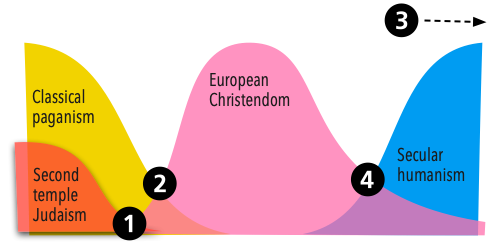

First, we should affirm the seriousness of the prophetic engagement of Jesus (1) and the apostles (2) with the historical situation of first century Israel and its relation to the nations of the Greek-Roman world.

Secondly, we should affirm, as a matter of fundamental theological conviction, the final triumph of the creator God (3), whom the church serves throughout the ages as a priestly community, over the evil and decay that are endemic in our world (cf. Rom. 8:20-21; Rev. 20:11-21:8). The creator God will have the last word. He will make all things new.

Thirdly, we should apply ourselves to the difficult task of constructing a credible prophetic story about the place of the church in the modern world (4). We need our own eschatological vision which is not just an uncritical and anachronistic reproduction of first century expectations.

We are understandably leery of attempting this because of a long history of false and fanciful predictions about the imminence of the second coming of Jesus. But that woeful catalogue of errors is simply testimony to the fact that we have all along been trying to appropriate eschatological perspectives that were never intended to function beyond the historical horizons of the early church.

Any new prophetic narrative for the church needs to be grounded in, responsive to, and explanatory of historical reality as we encounter it now. It may well draw on biblical types and analogues—the exile, for example. But it will gain its credibility and relevance from the fact that it candidly addresses the real experience of the post-Christendom church.

Where are billions of people going to fit on earth and do we want to live forever? No one in the first century thought about this. .it was all about judgement for them.

Dear Andrew, just this morning, I lay early awake thinking of an theological eschatology and how we can tech the mainstream the historic-focused eschatology of Jesus you declare in this and many other of your Posts… and than, came your insisting Postost-post.

Now, I have to confess, my heart beats with the groundbreaking decision of Wolfram Pannenberg, who in his systematic theology turned K. Barth upsides down.

1. Apocalysis (=God’s self-revelation) as history!

As the article in wikipedia is the way god shows up. I believe, that a monistic instead a dualistic worldview should fit better to a Jewish sort of thinking.

„Pannenberg’s understanding of revelationis strongly conditioned by his reading of Karl Barth and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, as well as by a sympathetic reading of Christian and Jewish apocalyptic literature. The Hegelian concept of history as an unfolding process in which Spirit and freedom are revealed combines with a Barthian notion of revelation occurring “vertically from above”. While Pannenberg adopts a Hegelian understanding of History itself as God’s self-revelation, he strongly asserts the Resurrection of Christas a proleptic revelation of what history is unfolding. Despite its obvious Barthian reference, this approach met with a mainly hostile response from both neo-Orthodox and liberal, Bultmannian theologians in the 1960s, a response which Pannenberg claims surprised him and his associates.[2]A more nuanced, mainly implied, critique came from Jürgen Moltmann, whose philosophical roots lay in the Left Hegelians, Karl Marx and Ernst Bloch, and who proposed and elaborated a Theology of Hope, rather than of prolepsis, as a distinctively Christian response to History.“

2. Because of this pannenbergiensis-centered thinking I end 2000 in the footsteps of Walter Wink, who prefers a monistic (against a dualistic)) worldview. Walter Wink impressed me with his concept of the Powers Trilogy. I feel your approach fits perfectly to this two theologian superpowers.

Be encouraged to continue your exegesis

A blessed new Year 2019 from Germany.

@Helge:

Thanks, Helge. I wonder if you saw this post about Pannenberg’s “The Crisis of the Scripture Principle”: “Wolfhart Pannenberg backs the narrative-historical method (up to a point)”. The problem I would have with the thesis you have outlined is that it is still essentially theological rather than historical. It does not account for historical events. It does not really understand the Jewish prophetic-apocalyptic tradition.

I have often thought that the main difference between the OT and NT prophets and the prophets of our day is a difference in “guts.”

One thing I’ve thought in considering this issue that is different, though, is that we are dealing with the people of God in a much more decentralized manner. There is no single Empire whose fate defines the fate of the known world. Instead, the people of God face a multiplicity of concrete situations depending on their location.

Even to identify the rise of secularism as an impending crisis — that’s certainly true for what we loosely consider “the West” but is not necessarily true worldwide.

There are certain crises like the environment that we could point to as being shared by all the people of God, but past that, it’s much trickier. I feel a lot more confident in identifying the eschatological experience of the church in the USA than in identifying the eschatological experience of the church everywhere.

@Phil L.:

Agreed, which is why I focus on the Western context as the direct continuation of the biblical-Christendom narrative but also partly on the assumption that, sooner or later, the rest of the world will follow us dow this road. We’ll see. In any case, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t offer some resistance to globalisation and highlight local and regional narratives.

@Andrew Perriman:

This is where, I think, the discipline and work of Contextual Missiology begins to dovetail with the imperatives of your narrative-historical perspective, Andrew.

The focus of CM is on an interaction of Scripture with Culture and Context and how the Church grows and fills the space within that context.

One of the perspectives that emerges from CM is the idea of ‘signs of the times’—which indicate how God is specifically at work in a particular culture. In this case, the secular humanistic cultures of the West.

In truth, much less work has been done via CM with respect to the West. As a discipline it arose out of the need for traditionally (Western-)missionary-receiving nations to be allowed to evoke their own contextual missiologies and theologies, without reference to the overbearing cultural hegemony of the West.

The need for CM work was initially evinced by indigenous leaders, such as the Tawainese leader Shoki Coe, but it came to be echoed and aided in its development by missionaries, not unlike Lesslie Newbigin, who on returning to the Western contexts that they left during the last days of the Christendom era, came to realise that the post-Christendom West now had far more in common with the traditional missionary fields of the Majority World, i.e. were now in every sense a ‘mission field’ themselves.

All of this is to say that, if the challenge you are making at the onset of 2019 is to be heeded and put into some form of praxis that goes beyond the theologian-centric community, it may find some significant support from contextually-orientated missiologists.

No idea if that’s useful or valued here, but there’s my two-penneth!

@John:

That’s a very interesting perspective. I’ve generally thought of contextual missiology as limited either to the rather condescending cultural translation of Western religious concepts or to the more creative work of developing indigenous alternatives. It’s only really when we consider the return to the Western context that we begin to sense the prophetic power of the post-Christendom narrative (Newbigin). That insight can then be worked in two directions—back to the biblical narrative by way of a historical eschatology, and forward to the reintegration of post-colonial missiology into a broader narrative of globalisation.

Thanks, again; this is helpful. In recent years as I have wandered in “post-evangelical” exile (though by your definition, I’m still “inside”), it has seemed to me that the evangelical churches of North America (my context) are rather like ultra-conservative Jews, patiently awaiting a Messiah who has already come and who is not coming again.

I’m afraid that, at least in North American context, it is going to be exceedingly difficult to frame a prophetic stance that meaningfully engages with the historical circumstances of the churches. My private intuition is that if there are any “prophets” speaking in our time — warning of terrible “under the sun” consequences of one or another form of idolatry — it is the climate scientists, and the NA evangelical churches seem for the most part very loath to concede that they might have a point. We are, it seems to me, part of the problem, which makes our circumstances and posture somewhat analogous to the religious establishment that was opposed to the specifics of Jesus’ prophetic message in His context.

I wonder whether it may be that a catastrophe as awful as what befell Old Israel might lie in the future of the North American evangelical churches.

Note “direct engagement with history”.

NOT “History Written in Advance(TM)”.

@ Andrew

If the result of Jesus mission was the judgment of “Second Temple Judaism (70 — 135 CE) + the defeat of “Classical Paganism” (4th century), but then “European Christendom” that followed eventually dwindled and was superseded by “Secular Humanism” (around 1800 CE), that is not much of an eschatological victory for the Lord God, is it?

How about considering “Secular Humanism” as (philosophical) Paganism in disguise?

@Miguel de Servet:

It strikes me as quite remarkable that Paul had the prophetic conviction to proclaim to the whole pagan oikoumenē, from Jerusalem as far as Spain, with an audience with Caesar along the way, that the God of Israel had put the crucified Jesus in a position both to judge and rule over this world. In historical terms, this was fulfilled with the conversion of Rome and the inauguration of a Christian civilisation that dominated Europe for 1500 years or more and was exported to much of the rest of the planet. If by “eschatological” you mean an absolute transcendent transformation, then, of course, Christendom fails the test. But I think that Jewish prophetic-apocalyptic thought of the period imagines, in the first place, solidly political outcomes, and I think that my interpretation of the New Testament fits that perspective very well.

@Andrew Perriman:

If by “eschatological” you mean an absolute transcendent transformation, then, of course, Christendom fails the test.

By “eschatological” I certainly don’t mean the Catholic Novissimi (Death, Judgment, Hell and Heaven, BTW Resurrection is not even explicitly included). I mean what in the Bible is called “last days”, that is the series of events, at the end of history, that lead to the Final Judgment.

I wonder what you mean by “absolute transcendent transformation”.

I think that Jewish prophetic-apocalyptic thought of the period imagines, in the first place, solidly political outcomes, and I think that my interpretation of the New Testament fits that perspective very well.

I do believe that eschatology entails “solidly political” aspects, but certainly does not consist of them.

I consider the famous dictum, Die Weltgeschichte ist das Weltgericht (“world history is the world’s judgment” — usually attributed to Hegel, although it is by Schiller) simply incompatible with Christian eschatology.

I mean what in the Bible is called “last days”, that is the series of events, at the end of history, that lead to the Final Judgment.

Do you have in mind particular texts where “last days” refers to the end of history?

@Andrew Perriman:

More “last day”, actually. Contrary to all attribution of “realized eschatology” or “inaugurated eschatology” to the GoJ, witrh this expression, the GoJ refers to the end of history. See John 6:39,40,44,54; John 7:37,11:24,12:48.

Recent comments