This is the third of three posts outlining the biblical narrative for the purpose of constructing a narrative theology for mission. The first part presented us with Israel as a new creation people called to worship and serve the living God, in the midst of hostile nations, over a long period of time. That traumatic story generated the belief that God would decisively save and restore his people and would eventually establish his own rule over the Israel’s neighbours. The New Testament gives its version of how that hope would be fulfilled through the faithfulness of Jesus and the testimony of the churches. This is explained in part two.

In this section I consider, in a very cursory fashion, how that story has played out over the last two thousand years and how I think it shapes the identity and purpose of the post-Christendom church.

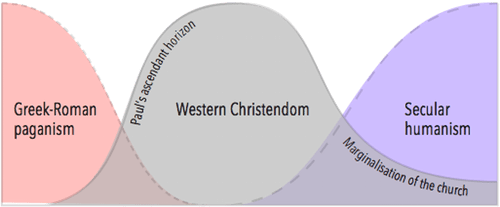

The rise and fall of western Christendom

If we allow ourselves to think and read historically rather than theologically, realistically rather than idealistically, we may conclude that the conversion of the Roman empire in the fourth century was the victory of Christ over the opponents of YHWH and his faithful people predicted in the New Testament.

This presents us with a dramatically transformed political-religious situation in which 1) the nations that were formerly under the control of Rome confessed that Jesus, the Son of God, was Lord—in place of the old gods and above the emperor; and 2) the church functioned as a dedicated priestly-prophetic people, mediating the presence and teaching the ways of the one true living creator God in place of the old pagan priesthoods. Historically speaking, it was a simple matter of régime change.

Fifteen hundred years later another revolution got underway in Europe—a long, drawn out cultural revolution, at times quite violent and dramatic, but mostly too slow for us to panic over. The Christendom worldview was overthrown, the church was kicked out of office, and a new “priesthood”—a humanist-scientific intelligentsia—was given the task of promulgating a whole new paradigm for modernity. That paradigm is still under construction and presumably always will be—there is no end in sight. But what is clear is that western societies expect little or no input from the church. There is no God to serve, no Law to teach, no Lord to confess, and if we need to be saved, we will just have to do it ourselves.

It’s debatable, of course, whether the rise of western Christendom was foreseen in scripture—I happen to think that the idea makes excellent narrative-historical sense. But the fall of western Christendom, the loss of faith in Christ as the resurrected Son of the living God, certainly was not foreseen.

But it happened. It’s a huge part of the church’s story—on a scale with the exodus or the exile—and we are still dealing with the consequences.

I suggest, therefore, that a narrative theology, if it is to give serious guidance to the church today, has to reckon not only with the persistent identity and vocation of the people of God but also with the particular contingent features of the historical landscape that we find ourselves in.

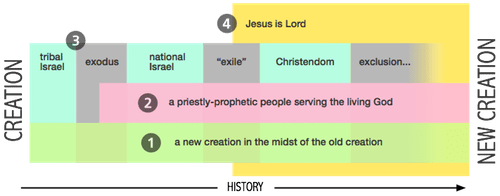

In the diagram (click image for a larger version) the lower two layers comprise the unchanging identity and purpose of the biblical people of God. Layers 3 and 4 summarise the historical aspect.

There is the obvious point that in the fulness of time Jesus became Christ, Son of God, Lord by virtue of his resurrection from the dead (Acts 2:36; Rom. 1:3-4). But this itself was part of the more complex story of Israel’s troubled relationship with the surrounding nations, which is layer 3. Jesus became not simply a universal judge and ruler but the judge and ruler of first century Israel, judge and ruler of the pagan nations of the Greek-Roman oikoumenē (Acts 10:42; 17:31).

1. The ontological substrate of a new creation identity

The narrative has given us an ontological substrate for the identity of the people of God in the call of Abraham to be a new creation in microcosm in the midst of the nations, recipients of the original blessing of the world and transmitters of that blessing to its neighbours.

Both actually—though imperfectly—and symbolically the church is and stands for how the creator intended humanity to be. It is a sign to the world of the fact and fallenness of creation and of the perseverance of the creator. It should also be a sign that God ultimately will renew all things, having consigned all that is painful and evil to the destruction of the lake of fire, to use the language of John’s fierce apocalyptic vision (Rev. 21:1-4).

So the church must learn how to embody the idea of “new creation” in its corporate life. This is to be understood functionally as an obedient response to the Spirit of life, which has replaced the Law as the determinant of life as God intended it to be.

2. A priestly-prophetic people in the service of the creator God

The “new creation” theme tells us what the church is. What the church does is given to us in the priestly-prophetic vocation, which goes back to the promise made to Moses: “if you will indeed obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession among all peoples, for all the earth is mine; and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex. 19:5–6).

The people of God has been qualified and equipped to serve the interests of the living God, as a priestly-prophetic community, through the changing and extremely challenging circumstances of its history. Any official “priesthood” within the people of God—the Aaronic priesthood, the Orthodox, Catholic or Anglican priesthoods—should in principle be only a sign and safeguard of the priestly function of the whole community.

As a priestly people, the church worships and serves the living God in its midst, teaching his ways to those who may come to learn about him. The church mediates, presumably in both directions, between God and the world.

As a prophetic people, it embodies in its theology and practice the coming action or intervention of God both in history and at the end of history.

The priestly function tends to prevail during periods of relative stability—when Israel was a nation in the land, or during the age of European Christian hegemony.

The prophetic function becomes more relevant during periods of upheaval and transition: during the exodus the tribes journeyed as refugees in the hope of gaining the land; exiled Israel, subject to pagan empires, clung to the hope of deliverance, return, restoration, and ultimately of kingdom; and the excluded church now searches for a new vision of its place in the world, a new hope of divine “action”. Perhaps for now we have little more than the final prospect of a new heaven and a new earth by which to set the missional compass, but the narrative teaches us to look for credible historical developments and outcomes in a foreseeable future.

3. History just keeps happening

The narrative shape of the Old Testament material is easy enough to grasp, but the tendency has been to think that the narrative journey comes to an end when we get to Jesus and the founding of the church at Pentecost. Subsequent events are described, but the assumption is generally that they all belong to a remote end-times, the end of history. They are held to be of doctrinal importance, but they have no practical bearing on church and mission—unless we happen to think that the return of Jesus is imminent and an incentive to get off our backsides and evangelise.

I think this is an unhelpful way of thinking, for two reasons.

First, it gives us a poor impression of how Jesus and the early communities of the resurrection understood what the God of Israel was doing in the first century (see part two).

Secondly, it denies us the opportunity to make good prophetic sense of our own place in history.

A narrative theology should not merely tell the “big story” of God. It should facilitate historical self-awareness. It should enable the church in the West, as a new creation people in the midst of an aggressively secularist culture, charged with the task of serving the interests of the living creator God, to address the challenges and opportunities presented by its exclusion from the centres of influence. A narrative theology should provide an account of the crisis consistent with what has gone before, and should frame the prophetic task of imagining plausible new futures.

I would suggest that much of the creative, imaginative, even subversive work that is being done under the banner of mission and church-planting these days is a concrete attempt to imagine new plausible futures for the church in the western context. It is narrative theology in action.

4. The good news about Jesus

Where does the “gospel” come into this? The good news in the New Testament was that God had raised Jesus from the dead and had given him the authority to rule at his right hand. The immediate historical implications of this were that 1) the government of God’s people was taken from the Jerusalem hierarchy, represented by Herod, the Sadducean aristocracy, the Pharisees, and the scribal caste, and was given to the Son of Man; and 2) that Jesus was eventually confessed as Lord by the nations.

That good news is history, but the affirmation at the heart of it remains true and valid: Jesus is Lord; the one who died on the cross for the sins of his people represents for us, embodies for us, enacts for us the supreme authority that would normally belong to God alone:

he raised him from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the one to come. And he put all things under his feet and gave him as head over all things to the church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all. (Eph. 1:20–23)

That is still our gospel, it is the most important thing that we have to say in the world, even though we proclaim it under very different historical conditions.

If people believe this message and are willing to put off the old humanity, they will be embraced by the creator, they will become part of a new creation people for whom Christ died, they will be recruited into priestly-prophetic service, and they will gain the real hope of being part of the new heaven and new earth.

Andrew, have you seriously considered the Paul Within Judaism perspective that Mark Nanos writes about? I think it makes sense to keep Israel Israel and Christian Gentiles the “nations” that turn to Yahweh and bring tribute to Israel.

You wrote, “We may conclude that the conversion of the Roman empire in the fourth century was the victory of Christ over the opponents of YHWH and his faithful people predicted in the New Testament.” It almost sounds here like you identify 4th-century Rome as the “nations” that turn to Yahweh after the kingdom of God is established. But if I’m not mistaken, in other posts you identify 4th-century Rome as the kingdom of God.

At times I think you do a great job of recognizing that many things in the New Testament were for Jews only, but at other times, your perspective looks like another form of supersessionism.

@Peter:

I think that Paul, like Jesus, would have had the basic Old Testament paradigm in mind: restored Israel at the centre of what would effectively be YHWH’s empire—the nations oriented towards Jerusalem rather than Babylon or Rome. I think, however, that by the time of the writing of Romans he was beginning to lose faith in this vision. It was not looking as though the inclusion of Gentiles would make Israel jealous and provoke national-level repentance and confession of Jesus as Lord before wrath came upon the people. So he clung to the hope that Israel would repent after the judgment that we know with hindsight took the shape of a devastating war against Rome. He did not live to see the outcome, so as far as Israel is concerned, his eschatology is inconclusive.

It almost sounds here like you identify 4th-century Rome as the “nations” that turn to Yahweh after the kingdom of God is established. But if I’m not mistaken, in other posts you identify 4th-century Rome as the kingdom of God.

The coming of the kingdom of God, as I understand it, was YHWH actively establishing his rule in history, first with respect to Israel, then with respect to the nations. The conversion of the nations of the Greek-Roman world, or of the Roman Empire, was one climactic moment in that process. It meant that not only the scattered precursor churches but the nations and peoples of the region as political entities acknowledged one God and one Lord. Christendom, therefore, was the concrete historical embodiment of victory of YHWH over the gods of the nations—including the “god” Caesar.

The question about supersessionism is too fraught to deal with sensibly. Within the purview of Paul’s eschatology, it is somewhat beside the point. His overriding concern was that there should be faithful, obedient, righteous and persistent communities of believers, bearing witness across the empire to the future rule of God over the pagan nations. These communities were rooted in the promises made to the patriarchs, and they could expect to inherit the new “world” that would come with the parousia (cf. Rom. 4:13). I imagine he expected these communities to remain Jewish-Gentile hybrids (whatever happened in Palestine), but it didn’t work out that way.

Recent comments