My argument about the historical frame of the Christmas stories and of Simeon’s prayer in particular has been subjected to sustained criticism by Peter Wilkinson, who is certain that at least in the latter case there is reference to the salvation of the nations.

Since Peter is unconvinced by the exegetical arguments, it may help to explore what is going here at the hermeneutical level. One way to account for the disagreement would be to view it as a question of how much respect we have for contextual boundaries. Peter takes the popular line that contextual boundaries may be disregarded in order to preserve traditional interpretations. We naturally want the Christmas stories to be about us. We have a hard time accepting the idea that the traditional discourse of Christmas—the carols, the readings, the nativity plays, the evangelistic sermons, not to mention the doctrine of incarnation—is all a massive over-determination of the texts. I take the view, on the other hand, that contextual boundaries should be respected, even if this means that traditional interpretations are weakened, sidelined, deferred or rejected.

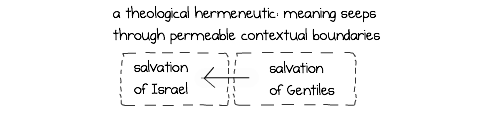

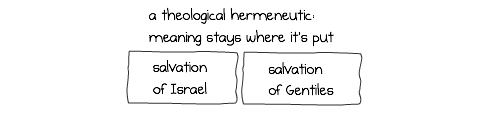

In much popular interpretation the boundaries established by context are permeable: meaning seeps through under osmotic pressure from elsewhere and contaminates the original text.

A narrative-historical hermeneutic, however, respects the impermeability of contextual boundaries. If there is no good exegetical reason to think that Simeon has in mind the salvation of Gentiles (and I don’t think there is), we should resist the temptation to read that thought into the text simply because from our perspective it is a matter of great importance.

In this instance, as with the interpretation of much of the New Testament, there are three types of context to take into account: the immediate literary context, a remote literary context, and a historical context.

1. The immediate context of Simeon’s prayer makes it unlikely that a reference to the salvation of Gentiles is intended in Luke 2:30-32. This prospect is not entertained elsewhere in Luke’s birth narrative, which depicts Jesus consistently as the king who will save his people Israel from their enemies. We are told explicitly that Simeon has been waiting for the “consolation of Israel”, and in his remarks to Mary following his prayer he says that Jesus “is appointed for the fall and rising of many in Israel” (Lk. 2:34). Finally, the prophetess Anna speaks of Jesus “to all who were waiting for the redemption of Jerusalem” (2:38). None of this precludes a tangential reference to the salvation of Gentiles in verse 32 but it weighs quite strongly against such an inference.

2. The remote literary context is usually made up of Old Testament texts which are either overtly quoted or covertly alluded to. They make up the active memory of the community that interpreted the events of Jesus’ birth, life and death—and indeed the memory of Jesus himself. We have to ask, therefore, to what extent the meaning of something that is said in the New Testament is to be determined by the memory of Old Testament arguments and narratives

In this case the relevant texts, in my view, are found in the Septuagint translations of Psalm 98 and Isaiah 52:

Sing to the Lord a new song, because the Lord did marvelous things. His right hand saved for him, and his holy arm. The Lord made known his deliverance; before the nations he revealed his righteousness. He remembered his mercy to Jacob and his truth to the house of Israel. All the ends of the earth saw the deliverance of our God. (Ps. 97:1-3 NETS = Ps. 98:1-3 in English translations)

The voice of your watchmen—they lift up their voice; together they sing for joy; for eye to eye they see the return of the LORD to Zion. Break forth together into singing, you waste places of Jerusalem, for the LORD has comforted his people; he has redeemed Jerusalem. The LORD has bared his holy arm before the eyes of all the nations, and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of our God. (Is. 52:8-10 NETS)

Both texts speak of the salvation of Israel as an extraordinary event that is seen by or revealed to the nations. Neither speaks of the salvation of the nations (Is. 52 describes the return from exile), though they both fit into narratives in which the rule of Israel’s God over the nations is envisaged (cf. Ps. 97:9 LXX = 98:9 ET). This is exactly what we have in Simeon’s song: like the watchmen of Jerusalem Simeon has seen the salvation of Israel that has been “prepared in the presence of all peoples” and which will reveal the righteousness of Israel’s God to the nations.

Since the subject is “salvation” rather than the “servant” of YHWH I don’t think Simeon—or at least Luke—has in mind passages such as Isaiah 49:6 LXX, which speaks of God’s “servant” as a “light of nations… salvation to the ends of the earth” (cf. Is. 42:6). This is an eventual outcome, but there is an important narrative or argumentative boundary between the earlier statement that Israel’s salvation will be seen by the nations and the later thought that salvation will be extended to the ends of the earth, which I think needs to be respected if the story is to be understood properly. So when Peter argues that Isaiah 52:10 means that the nations will experience the power of salvation because this may be “inferred from how the story turned out”, he is transgressing a boundary in the discourse: he has imported meaning from the end of the story into an early episode by inference.

3. In many respects, what is at issue here is the historical integrity of the New Testament. Even taking into account prophetic foresight, historical narratives are necessarily shortsighted, blinkered, partitioned. Understanding and outlook at any particular point in the narrative are contextually constrained. For example, it is historically inappropriate to suppose that either Anna or the Jews in the temple to whom she spoke under the “redemption of Jerusalem” in anything other than nationalistic terms. It is historically inappropriate to read Simeon’s words in the light of the eventual inclusion of Gentiles in the covenant people or Paul’s statement in Acts 13:47 that the apostles have been made “a light for the Gentiles, that you may bring salvation to the ends of the earth”.

If we read the New Testament theologically, we will permit ourselves to shuffle meanings around as we see fit in order to illustrate and defend our preconceptions. If we read the New Testament historically, we will have to slap hands when we do this, because the narrative of history develops under much tighter contextual constraints.

Recent comments