I’ll make this my last post on Bird, et al.’s lively—bordering on manic—response to Bart Ehrman’s book [amazon:978-0061778186:inline]. Chris Tilling is a good friend, so I need to tread a little carefully here. His argument is based largely on his published PhD thesis [amazon:978-3161518652:inline], which I have read and greatly enjoyed.

In chapter 6 of [amazon:978-0310519591:inline] he puts forward an analysis and critique of Ehrman’s basic christological narrative. At the heart of Ehrman’s project, Tilling thinks, is the distinction between “exaltation Christologies” and an “incarnational Christology”:

The earliest Christology, he tells us, understood Christ as a human like any other. He was later exalted at his baptism or resurrection to become Son of God, a divine being of some sort. As time passed, Christians gradually came to understand Jesus as “a divine being – a god – [who] comes from heaven to take on human flesh temporarily.” This incarnational Christology began early in the church, perhaps earlier than 50 CE, Ehrman speculates. In the letters of the apostle Paul one can see a transition between these two types of Christologies taking place. Only later were the earliest “exaltation Christologies… deemed inadequate and, eventually, ‘heretical.’” (119)

Tilling argues that the New Testament data simply doesn’t fit the chronological schema, that the use of Galatians 4:14 (“you… received me as an angel of God, as Christ Jesus”) as the interpretive key to Paul’s christology cannot be upheld, that Ehrman’s definition of “divine” is far too loose, that he misunderstands Jewish monotheism, and that he gets a number of other things wrong.

The substance of his defence of a high christology is presented in chapter 7. First, he suggests that central to the Jewish understanding of the uniqueness of God was “a pattern of language that spoke of a unique relationship between Israel and YHWH”. Secondly, Paul’s epistemology is relational: to know God is to be in relationship with him. So the critical question is this: “Is the pattern of language that describes the relation between Jesus and his followers, Christ and the church, analogous to or different from Israel’s unique relation to YHWH?” This brings us, thirdly, to the heart of Tilling’s relational christology:

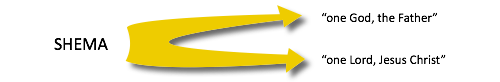

Instead of speaking of the relation between Christians and God over against idolatry, Paul instead speaks of the relation between Christians and the risen Lord over against idolatry. And what is more, Paul describes this Christ-relation with the themes and language traditionally used to describe the relation between Israel and YHWH…. For example, in I Cor 8:6, the Deuteronomic “Lord” (kyrios) is, for Paul, the risen Lord. For many, this verse is a clincher, showcasing a “christological monotheism,” including Christ in the Shema. All the Greek words of the Shema in the Greek translation of the Bible used by the earliest Christians are repeated by Paul in 8:6. The “God” and “Lord” of the Shema, which both identify the one God of Israel, are now split between “God” the Father and the “Lord” Jesus Christ. (141)

Old Testament stories that affirm Israel’s covenantal relationship with YHWH and which establish the “transcendent uniqueness” of YHWH “are retold by Paul, and rethought around the relation between risen Lord and Christ-followers”. So in 1 Corinthians 8 and 10 the argument against engagement in idolatrous practices is constructed in terms of the relationship between believers and the risen Lord.

Tilling then goes on to show how this works in 1 Thessalonians—not the obvious text to choose, but since Ehrman considers it our “earliest surviving writing”, it has polemical advantages. It is noted that Paul speaks of the relation of believers to Christ in much the same way as “Jews described relation to God”. The believers in Thessalonica hope in the Lord Jesus Christ, they wait for God’s Son from heaven, they will glory in his presence when he comes, and they stand steadfast in the Lord. In particular, Paul prays that to Jesus that he will clear the way for him, that he will work in the hearts of the saints—increase their love, strengthen them, and so on.

He concludes self-referentially (that is, he quotes himself):

In other words…, “the way Second Temple Judaism understood God as unique, through the God-relation pattern, was used, by Paul, to express the pattern of data concerning the Christ-relation.” This is a very Jewish(-Christian) way of saying that Jesus isn’t merely an exalted being, nor even just some kind of “divine god.” It is saying, in such a manner that corresponds neatly with our explanatory conditions, that Jesus is on the divine side of the line, that Jesus is, as other New Testament scholars would say, included in the “unique divine identity.” … Paul’s Christ is therefore fully divine, sharing the transcendent uniqueness of the one God of Israel. (144)

This is a sophisticated and attractive line of thinking, but I have the same sort of critique of it, more or less, as with Michael Bird’s and Simon Gathercole’s chapters. I think it is trying to make the lordship narrative—I stress narrative—do something which it was not designed to do; and conversely, I think it rather obscures or misrepresents what the narrative actually was designed to do.

One God and one Lord

I am not convinced that in 1 Corinthians 8:6 Paul splits the “Lord our God” of the Shema into “one God, the Father” and “one Lord, Jesus Christ”:

Arguably, the first part of the verse is an implicit affirmation of the Shema, alluded to already in verse 4: “we know… that there is no God but one”. The second part of the verse makes a separate statement on the basis of the distinction in verse 5 between “many gods” and “many lords”. I have suggested before that Dunn makes a good case for thinking that the confession of “one Lord, Jesus Christ” comes from a different narrative. So what we have is not a bifurcation of the Shema but a convergence of the traditional Jewish confession with the apocalyptic account of Jesus’ exaltation:

In any case, the affirmation that for Paul and his readers Jesus is kyrios does not explain how or why he has that status. Notwithstanding the confessional character of the verse, it’s a mistake to read it in isolation, apart from the apocalyptic narrative which everywhere in the New Testament accounts for Jesus’ lordship. The point of this will become clearer, I hope, when we look at 1 Thessalonians.

Concerning food offered to idols

I disagree with Tilling that in the argument against idolatry in 1 Corinthians 8 and 10 Paul makes the relation between believers and Christ directly analogous to the relation between Israel and YHWH.

The Israelites put YHWH to the test in that although, typologically conceived, they were baptized in the sea and shared in the spiritual food and drink, they then “rose up to play” and indulged in sexual immorality, for which they were severely punished. In the same way the Corinthians cannot assume that just because they have been baptized into Christ and share in the Lord’s supper, they will not escape punishment if they get messed up with demons.

So the analogy is between participation in the saving experience of the exodus and participation in the saving experience of Jesus’ death and resurrection. God is the author of both these saving experiences and he is glorified when the people participate rightly (cf. 1 Cor. 10:31).

It is true, as Tilling notes, that whereas the Israelites put YHWH to the test, the Corinthians risk putting Christ to the test, but the reason for this is not that Jesus is assumed to be equivalent to God; it is that he has a unique relationship as Lord with the believers, which again refers back to the apocalyptic narrative. This is brought out very clearly, I think, by Paul’s argument in 1 Corinthians 8:11-12:

And so by your knowledge this weak person is destroyed, the brother for whom Christ died. Thus, sinning against your brothers and wounding their conscience when it is weak, you sin against Christ.

The relational argument here identifies Christ not with YHWH but with those weak believers against whom the strong sin.

The apocalyptic narrative

The Lord Jesus in 1 Thessalonians is the Son who suffered, whom the Jews killed as they had killed the prophets before him, who was raised from the dead, is currently in heaven, will soon descend from heaven to deliver his followers from the coming wrath, will be reunited with them, and will crown them with glory. Alongside this narrative, notice, is another narrative about God: God raised Jesus from the dead, God calls them into his kingdom, the Jews displease God, the wrath of God has come upon the Jews, God will raise those how have fallen asleep and bring them with Jesus, God has destined them for salvation through our Lord Jesus Christ, God will keep them blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.

The Jesus story goes from suffering and death to being given the name which is above every name to coming back to rescue and vindicate his followers. [pullquote]The lordship of Jesus cannot be separated from this story, nor can this story about lordship be separated from the story of the early persecuted church.[/pullquote] Jesus has been seated at the right hand of God, above all rule and authority, everything has been put under his feet, he has been given as head above all things “to the church, which is his body, the fullness of him who fills all in all” (Eph. 1:20-23). Jesus has been made Lord for the sake of the eschatological community, and the eschatological community constitutes the fullness of the risen Lord.

Jesus is the firstborn among many brothers, they are conformed to his image—to the pattern of suffering, death and vindication (Rom. 8:29). He is the first fruits of the resurrection but others—those of Christ, those who have died in Christ—will be raised at his parousia (1 Cor. 15:23; 1 Thess. 4:14-17). He is the firstborn from the dead—that is, the first of many who will suffer and be vindicated (Col. 1:18).

I think Tilling is right to highlight relational dynamics in this whole debate. My problem with his argument is that, at least in this argument against Ehrman, he gives insufficient attention to narrative dynamics—to the apocalyptic narrative by which the lordship of Jesus is determined. The New Testament does not account for the lordship of Jesus simply by finding him on the divine side of a putative line between God and not-God. It certainly doesn’t construe it as a matter of God becoming Jesus. Rather, the New Testament accounts for Jesus’ God-given status and authority by telling a story of suffering, exaltation and return, in which he represents and acts on behalf of the suffering church. The lordship narrative identifies Jesus with faithful “Israel”, not with YHWH.

Andrew,

Thank you for your post as always. I am interested in how Christ’s preexistence inferred in the Gospel of John prologue and in 1st John (he “sent” his one and only son into the world) inform your apocalyptic narrative lordship Christology.

Thanks,

Billy

@Billy North:

My concern at the moment is to keep the apocalyptic narrative and the Logos theology of John 1 apart, even if a little artificially. Did you read “There are two Trinities in the New Testament and they are not the immanent and economic Trinities”?

@Andrew Perriman:

Andrew,

I must keep up with your posts more regularly my apologies. It was late last night when I read through your earlier posts. There is much to digest there but I did find them very challenging and interesting. I ended on your post regarding metaphysical categories that we use to construct Trinitarian theology. In that post you state:

“It is an objection to the use of the categories of a post-biblical metaphysics to reinterpret New Testament thought.

The metaphysics of the New Testament—if we must retain the term—is narrative-historical. It is grounded in creation, covenant, vocation, faithfulness, prophecy, eschatology, conflict, crisis, political transformation. I would argue that these remain perfectly adequate categories for speaking about Father, Son and Spirit today.”

I think I’m beginning to understand your premise. In trying to argue for a Trinitarian theology and the divinity of Christ we have to use postbiblical metaphysical categories that come from Greek philosophy. That might be an interesting exercise but it is not biblical. There might be some truth in it but by its very nature it’s just a purely intellectual enterprise, speculative, abstract and inconclusive.

So please confirm if I understand. You’re not arguing against Trinitarian theology nor the divinity of Christ. You just want to put the metaphysical language into the “background” and bring into the “foreground” the language of scripture which you term “narrative-historical”.

Plain and simple actually.

Cheers,

Billy

Hi Andrew,

In light of what you have said in this article, particularly in the last paragraph, I am wondering if you currently believe that there is anything in the New Testament that teaches us that Jesus is God incarnate, the second person of the Trinity, in the Trinitarian understanding that the church has taught for many centuries now.

Would you mind clarifying for me where you are personally in your study of this issue at this time? You seem to be going back and forth between seemingly quite blatant statements such as this that you do not share that belief and understanding and other statements that are more nuanced.

As you well know, this is a huge issue of great improtance for a great many Christians.

@cherylu:

I’m probably repeating myself here, cherylu. It seems important to me, as I just said to Billy North, that we don’t confuse two distinct New Testament narratives or arguments: the apocalyptic one about lordship and the Wisdom/Logos one about creation/new creation. Incarnation, word becoming flesh, belongs to the second one and not to the first, in my view. The first is saying something else—as far as the New Testament is concerned something much more important. These two recent posts have a bearing on the matter:

@Andrew Perriman:

Thank you Andrew. I will take a look at those two posts. I am not certain if I have read them both or not.

@cherylu:

I was wondering whether the trinity is so important and of such sentimental value, that propor critical assessment of this doctrine is not sabotaged from the get-go? If believing the trinity as honor or salvation contingency, then of course it won’t get the scrutiny it deserves.

Interesting post here by another bibliobloggers. I also added a comment. http://ntmark.wordpress.com/2014/04/14/thoughts-on-the-late…

Thanks. I think Michael is pretty much spot on.

Recent comments